For four decades, Knox Chandler has served as a versatile collaborator, contributing his guitar, cello, and bass to the oeuvres of acts ranging from The Psychedelic Furs and Siouxsie and the Banshees to R.E.M., Depeche Mode, and Cyndi Lauper. His career reads like a catalog of alternative music's greatest hits: contributing cello to R.E.M.'s Automatic for the People, arranging strings for Depeche Mode's Exciter, and spending a decade as Cyndi Lauper's musical director. Yet beneath this impressive CV lay an artist still searching for his own voice.

That voice crystallized during Chandler's decade-long residency in Berlin, where he developed what he calls "Soundribbons"—a real-time sonic technique that uses iPads to process and manipulate guitar signals. This meditative practice became a compositional method and a philosophy, requiring the musician to remain entirely present in the moment. The approach proved adaptable across genres, allowing Chandler to refine the technique through various collaborations while serving as head of the guitar department at the British Irish Modern Music Institute.

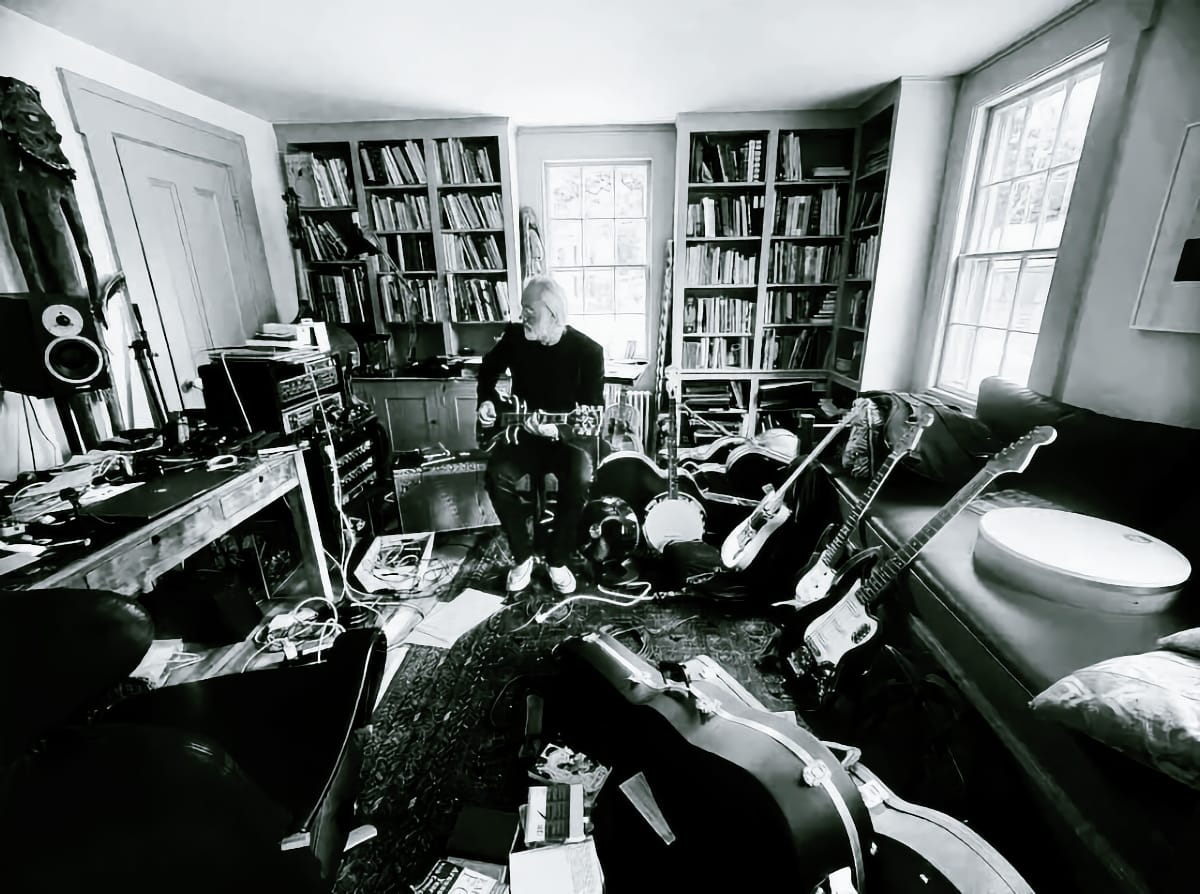

In 2022, Chandler returned to Connecticut to care for his ninety-year-old mother, settling in the shoreline area off Long Island Sound. "I like to say this place is incredibly beige, vacuous of all culture, but awfully pretty," Chandler remarked. But the dramatic shift from urban Berlin to rural New England lit some new creative fires. Chandler found inspiration in the rich natural environment where ospreys and bald eagles had returned after near extinction, where frogs created what he heard as symphonic counterpoint, and where walks through decomposing landscapes revealed unexpected beauty.

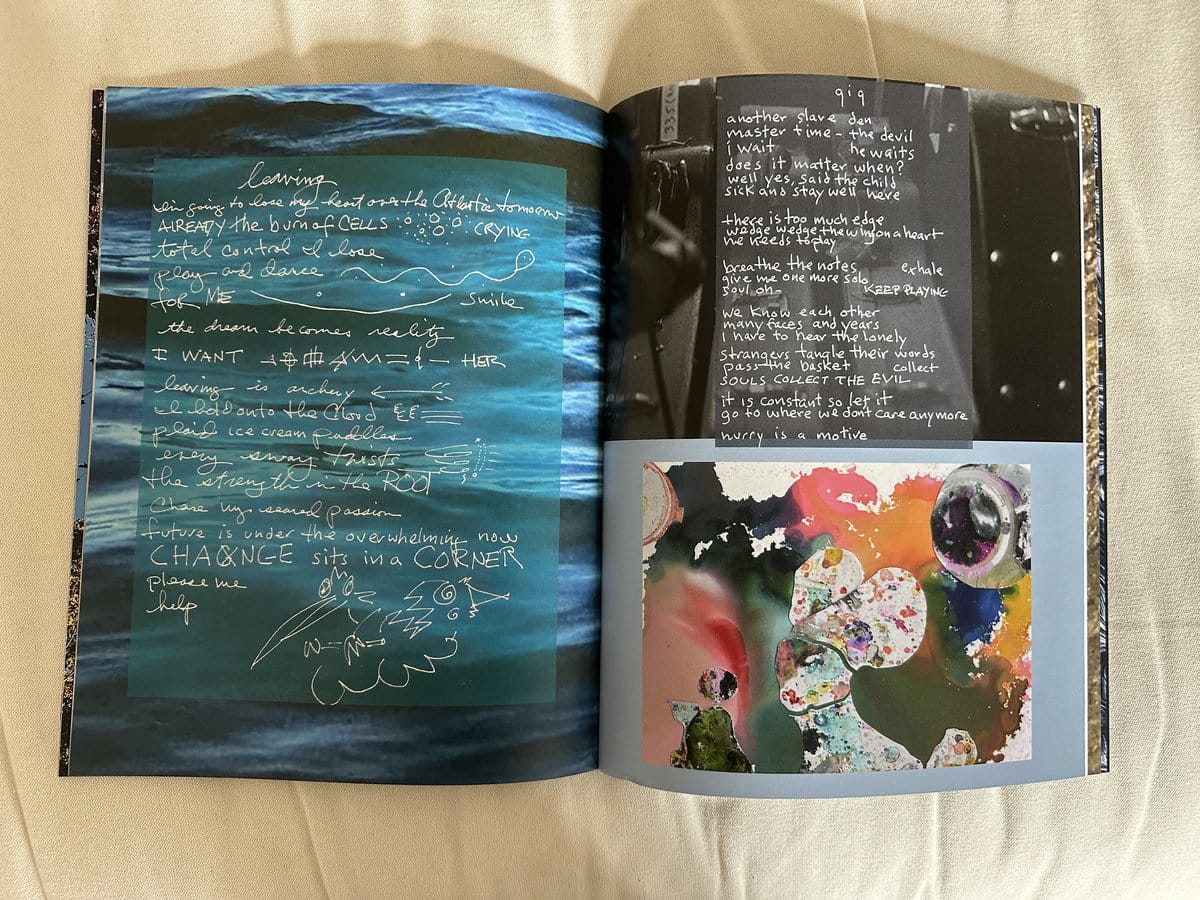

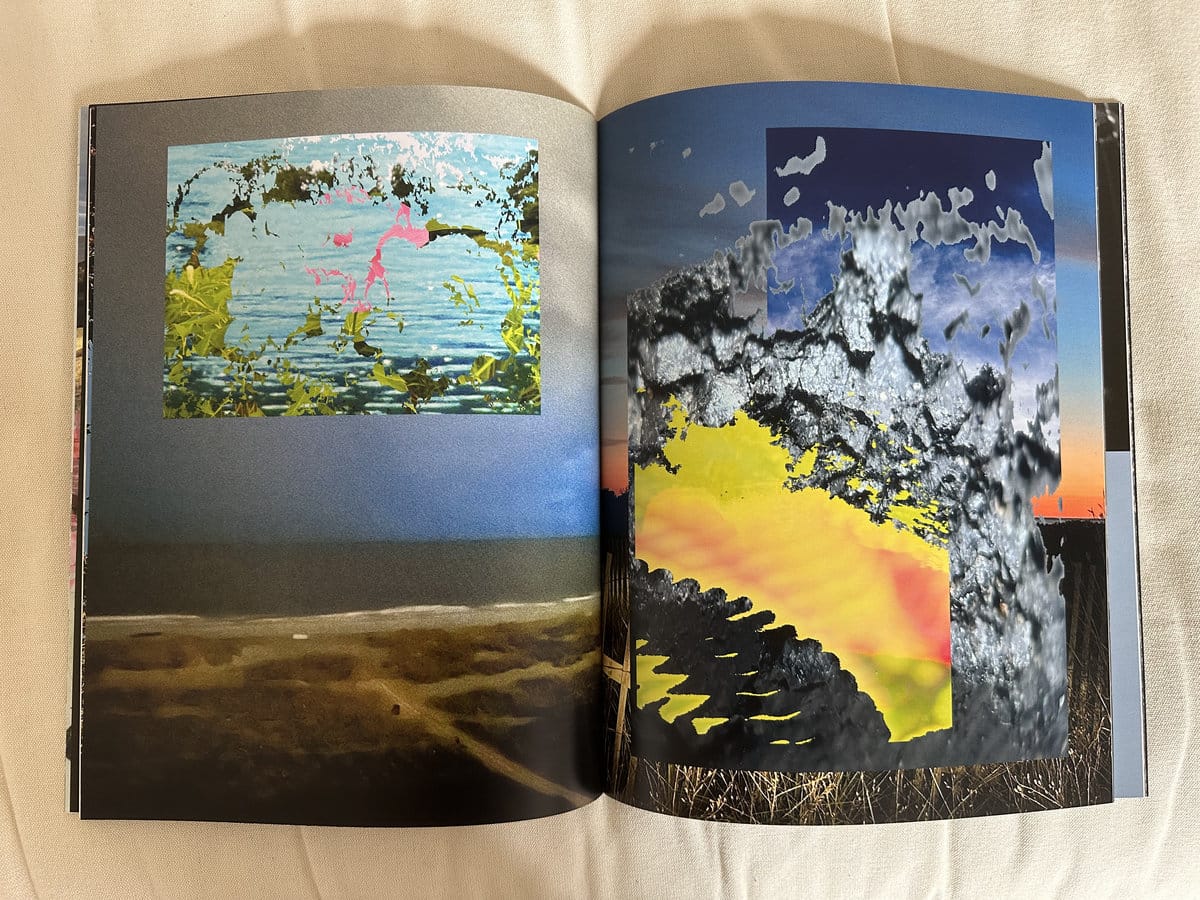

This environmental isolation became the foundation for The Sound, Chandler's solo debut on his new label Blue Elastic. Rather than a traditional album, the project exists as what Chandler calls "a musical memoir,” including an integrated book filled with paintings, photographs, sketches, and handwritten journals. Most of the accompanying ten tracks began with a Soundribbon session, building from guitar improvisations recorded in real time. Songs like "Mars on a Half Moon Rising" incorporate field recordings of the shoreline’s frogs, while "Branch" pays tribute to late trumpeter Jamie Branch. The project allowed the veteran musician to finally express what he calls "my truth" without compromise or external influence.

Knox Chandler recently joined host Lawrence Peryer for a Spotlight On podcast session. In their conversation, Chandler discussed his innovative Soundribbons technique, his transition from an urban collaborator to a rural solo artist, and how the Connecticut landscape influenced both the sonic and visual elements of The Sound. He also openly talked about what it means to find one's authentic voice after decades of supporting other artists' visions.

You can listen to the entire conversation in the Spotlight On player below. The transcript has been edited for flow, length, and clarity.

Lawrence Peryer: I’ve read about the various creative and artistic elements that go into The Sound. Was the genesis of this the recorded music, and then the project evolved? Or were you always thinking about a multimedia approach?

Knox Chandler: There's always been this visual thing that I connect to, and a lot of what I do musically is visual. I studied art as a child and had a split major as a musician-artist until my senior year in college. I put it down for a long time, but I got back into it after moving to Berlin. Even before I moved to Berlin, I was making these films and going out to project them and play them to an audience. They're very abstract.

So, when I arrived in Berlin, back in 2012, I locked myself in for two years and became deeply immersed in creating the soundscapes, which I call Soundribbons. These are soundscapes with no preexisting audio. I’m using an iPad, where I grab bits and pieces and process everything from step sequencers to wild reverbs to granular synthesis. They're never the same, and it's all in real time. I don't use any synthesizers or samples. It's like my version of what a guitar sounds like.

At the same time, I started creating these clips and doing the same thing with another iPad, where I process, mix, and select bits and pieces, and project them while performing the audio end of it. It's demanding, but I love it. You're really in the 'now,' and you're in the 'now,' and the whole purpose is to get lost in the 'now.' (laughter)

About that time, I was working with this guy, Peter Freeman, doing a record with him and Rick Cox, and Peter was a big fan of the way I worked with the guitar, and he wanted me to make a guitar album. So, in the back of my mind, I always thought, "Eventually I will do this."

I returned to Connecticut, and I started feeling increasingly inspired. In the meantime, I was working with Bobby Previte on the album Previte Chandler, which was released in February on Subsound. And so I was applying a lot of what I was experiencing in this area to that record. And then when I finished that, I was like, "Okay, I got a lot more time on my hands. I really gotta focus on doing this guitar album."

I started that process, and at the same time, I was working on these paintings, photographs, and whatnot. I went down the path of manipulating those which felt similar to the way I manipulated audio. And I was thinking, "Okay, and this is all connected to Salmon River," or "That's all connected to Chaffinch Island," or "It's all connected to the pond that's up through the woods there."

I don't know; it just naturally happened for me, which is kind of unusual, because usually I have to search for things to bring it all to fruition. I was probably well into documenting this experience when I decided, "I don't wanna do a CD, and I don't wanna do vinyl, but I want something tangible. So I'll make it a book." And I was able just to be able to look at the bulk of the writing I had done and the paintings and sketches and the Soundribbons that I was putting together as compositions, and going, "This is one of the same." It is, in fact, a documentation of my musical memoir, dating back to three years ago.

Pages from Knox Chandler's book The Sound.

Lawrence: There's sort of a freedom in the fact that even twenty years ago, you might have thought about this as maybe just complex CD packaging with beautiful imagery in it. But today, you get to completely reimagine what the format is for delivering this piece.

Knox: Yes. It's been a lot of work. And there had been some roadblocks. I almost went with the whole vinyl thing. But not a lot of people have record players. A book, however; I always like art books. This book depicts moments in a collage format. There’s a lot of collage work in there, bringing to life some of the feelings I had and some of the emotions.

It's a somewhat complicated experience, but I’m trying to find beauty in it all. And it's often that I find beauty is more powerful when it has contrast, like the beauty in flowers. It always is amazing when it pops up in some decomposition. Or like finding the beauty that crops up in this new, tough stage of my life, of trying to take care of my ninety-year-old mother, which isn’t easy.

Lawrence: You mentioned this music came to you in a different way than how you usually work. Why do you think it was different this time?

Knox: Well, I'm older. (laughter) All those projects I've worked on in the past—I've worked with a lot of different people, and they all brought me to this place. I figure that every time I’ve been in a studio, on the road, or played a gig or a television performance, I've always learned something. That's something I've always been very focused on: this life I’m living is about learning, and I’ve to keep learning.

I mean, every time I go into a session or work with someone, I try to bring my voice to it. I think I probably took a bit of a deep dive when I got here as far as spending a lot of time by myself, really trying to figure out what my voice is. I know I reinvented it in Berlin with the Soundribbons approach, but I knew it was time for me to stay put for a bit and just do the work.

And in the process, I learned about various stages, such as setting up a business—Blue Elastic is the label—and then I had to learn Adobe Illustrator to create the logo. I’m also going to work on this book, so I had to learn InDesign. And then I'm making these video clips, so I have to learn Premiere. And so every single day, I'm learning something. I even had to learn how to build a website rather than hiring people. I've always hired someone in the past, but I never learned anything. I might get frustrated—“Why did that happen?" And you get an answer, and maybe it was a mistake somebody else made, but you can't understand what the mistake is unless you experience it yourself.

At the same time, I’m learning a lot about myself, and that definitely reflects on what the music does. It's a product of the experience of being here, of this mixture of rural inspiration from urban inspiration, that sort of metamorphosis of where I am today. You also get some vapor trails of urban life in there, as well as moving back to Connecticut and being a caretaker for my mother for two years, which brought up all this other stuff.

Lawrence: I'm curious, could you talk a little bit about the Soundribbons approach? You walk into your work environment or the studio, and you have a blank sonic palette. What happens?

Knox: I've always been fascinated with the electric guitar. Going back to Jimi Hendrix, it wasn't his lead playing so much as the sound, the feedback, the tape manipulation, even like on Electric Ladyland, putting the jacks the wrong way around in a wah pedal to get that flute sound—sounds like seagulls. And I mean, all that stuff fascinated me.

By the time I arrived in New York, I was experimenting with various processing and stomp boxes. When I joined The Psychedelic Furs, that's when I got into the TC 2290. It’s got a sampler in it, but it's got this amazing sounding delay with all this modulation. You have to program it like a computer. I got deep, way deep into that. By the time we recorded the World Outside album, I had spent some time with Steven Street, who was producing the record, manipulating the TC 2290, which sounded incredibly exciting.

There were also a lot of synthesizers around, but they all, to me, sort of sounded the same. I had a lot of respect for it, but I wanted to try to make the guitar do what synthesizers did to some extent. I enjoyed the graininess that you get from a guitar string, a cello, or even an electric trumpet, with just the sound of the breath passing through it, and then you manipulate it like you would a sine wave or a saw wave. That got me really interested in processing the instrument.

By the time I arrived in Berlin, I was at the tail end of my work. I did ten years with Cyndi Lauper, and that ended. I'd done some movie stuff. I just felt like I had to do something different. I had to change things up, and I didn't want to hop on another legacy act. I thought I had to get back to what was truly me. I was a tourist to what I was over the years. I never really engaged. I never really put everything in.

So I moved to Berlin, originally to live with Budgie, the drummer from the Banshees, who was a very good friend of mine. I didn’t take any foot pedals or rack space stuff. It'd be just an iPad with an interface, a computer, a guitar, and a suitcase. I approached it as if the whole workstation would be on the computer and the iPad. I did a deep dive with that, and once I got in there a little bit, I started hearing what could be the new me. Certain things spoke to me then. So, there’s buying a lot of apps that I don’t even use, combining apps and other things, and then also working with the computer to learn Ableton, and later, Max for Live.

Then I started performing with Budgie. I played with some dance music people, some free jazz people, and even this indigenous Nepalese band. I realized that this set-up works with anybody I'm playing with. It crosses genres, which excited me. "Okay. So I'm onto something good."

The name Soundribbons just came to me because, visually, that's what it feels like. It feels like I'm sending off these sorts of multiple ribbons, and sometimes they wrap around something, allowing me to sit there and maneuver and manipulate them into a shape on some compositional level. These things can go on forever, or you can compose on the spot as short pieces of music. It will be whatever instrument is plugged into it, mostly a guitar, so there's no preexisting audio, no synthesizers, no drum machines, and no samples.

At the beginning, I’d sit there, start it, and then stop it. "No, that's not it." I'd start it and I'd stop it. "No, that's not it." Then I realized I couldn't do that. That's not working. That sort of defeats the purpose of no preexisting audio. Well, there should be no preexisting thoughts of what I'm going to do with this, either.

It’s really about being in the moment and, in that moment, grabbing something that just comes to you. This goes back to a theory I have about the beauty of the first take. Because quite often, the best ideas just come right away. They're immediately there. And then, there’s this intercession; the producer goes, "Oh, that's brilliant," and then you spend the next half an hour trying to make it better. Sometimes you might make it better, but the rest of it is ruined. And I thought, "Okay, so where does that come from?" I like to say it's as if I’m channeling it from somewhere outside of myself. I call it a gift.

So here I am, creating this thing on the spot. It could be just the groundwork for what is to come. And then I start adding to it, and that's when the chaos begins. When I get into that mode, I start hearing the beauty in it—where I have to direct it, and how I can massage it so it works as a piece of music. And when it's really good, I get lost in it. I've recorded many of these, and I listen to them quite frequently. That has been the basis for all my compositions these days.

I start with a Soundribbons thing. I might make it five minutes long, and then I’ll sit there and listen, and that’s where I start hearing things. And then I'll start editing it and adding other elements, maybe, and start laying down percussion on my bass. That's been the way I've been working these days. That might change next year, but it's been something I’ve found to be pretty fruitful artistically for me.

There's one piece on the record, a piece "Mars on a Half Moon Rising," where I recorded the sound of frogs. It gets loud out here some nights, and I caught this one moment where I recorded about five to ten minutes of these frogs. I sat there and listened to it. Constantly. And I thought, “This is a symphony. It sounds so composed." There was counterpoint, and there was register. It just blew me away. And I played it for my friend Sue Jacobson, and she's said, "You should put a record out of these." And I said, "Yeah, but that's not really what I'm doing these days."

I was right in the middle of recording this record, and I listened to it over and over again. I put it on in the studio, and on a first take, I put on a Soundribbon with it. Perhaps it’s because I listened to it so much, and I was somehow connected to it on a deeper level, because it wasn’t purposeful. But all of a sudden, I heard what it was going to be. I was like, "This is it." I sat down with the guitar and fooled around with this melody, and it fit perfectly. And then there were all sort of sentimental feelings about Mars Williams's death. He was a very close friend, and so it's almost as if it’s to him. His name's in the title. It's not something I think he would ever play, but it was heartfelt. It's my sort of pouring my love out to this guy who taught me so much and was so great.

That song "Branch" is for Jamie Branch, who was working with Mars and me on the Albert Ayler Christmas shows. The last time I saw her play was in Berlin before I moved back here. She had this one piece where she was squeaking her sneakers on the stage, and so I was like, "Okay, I gotta get that on the guitar." So there are just little gestures like that, but every song on that record started with a Soundribbon, except for "Mars,” which started with the frogs.

Lawrence: You've spent so much of your time in other musical contexts, whether it's part of some of these bands that you’re working with or supporting other artists. Now, it seems you have the chance to implement or express your own thing.

Knox: You're absolutely correct. I think it's because I moved back to Connecticut. I'm two hours away from New York City, and it's hard for me to get there. I mean, I've been there about two or three times over three years to do some session stuff, but I'm not being pulled away from what I'm doing out here.

I have recently been working with the New Haven Improvisers Collective. A couple of nights a month, I go in there and play with those guys and do shows here and there, but I'm isolated. It feels very isolated. I have a lot of time to think and reflect. I don't see myself, at sixty-six, jumping down on stage singing "Girls Just Want to Have Fun." I just don't—my mates seem to do that pretty well. I don't see myself doing it.

I've never lost the love and passion for music. I've been able to express myself alone, primarily out of sheer joy, and it's not like I'm trying to be something I'm not. I've come to terms with the fact that this is who I am. I mean, this record and the entire book are nothing but my truth. I went into the project that way, and to me, it's a success because, whether you like it or not, this is who I am right now. It is just what it is, and that's a beautiful feeling. That feels very freeing for me, and probably the first time in my life I've been able to do it and feel that way.

And yeah, I guess it is a little self-indulgent. I don't feel like it is, but it's very vulnerable. Some people can look at it and say, "Well, he's not really an artist," or "He is not really a writer," or "He's not really a guitarist," or whatever, those voices that you sometimes get in your head. I mean, it is what I am. It's just my truth.

The first round of drafts I did of the book, all the text that's in there, I had text printing, different fonts, and a good friend of mine, Rick Moody, who's a writer, he went through it and he said, "Knox, you are an artist. Your music's great. The thing is, this is similar to your journaling. You should go back and do it all in handwritten." He was right. It took me a while to do it, but I handwrote everything out, and I go, "Yeah, this is exactly what it's supposed to be. It is a journal." Simple as that. It's not a book of poems. It's not a book of art. It's a journal, just like the album is a journal.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments