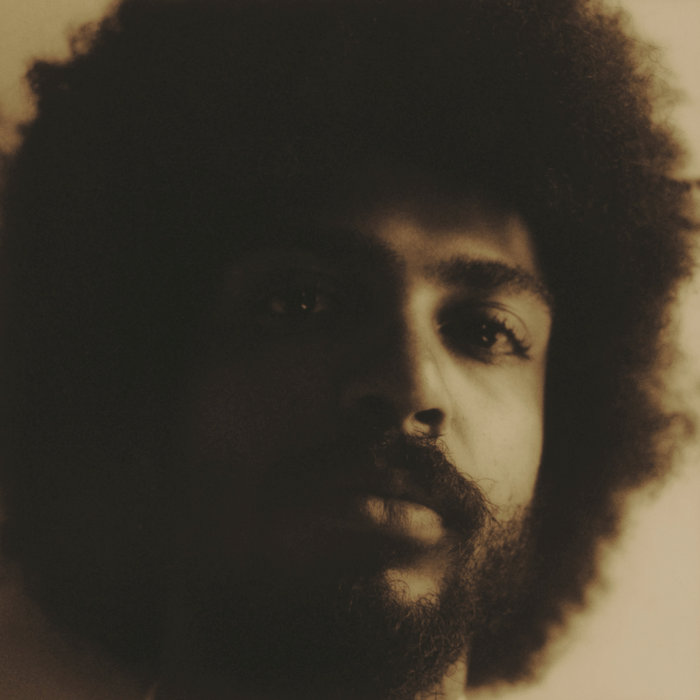

In a music landscape where polished studios and large creative teams often shape the final product, Montreal's Yves Jarvis—born Jean-Sébastien Yves Audet—tells a story that stands out for its humility and determination. His fifth album, All Cylinders, recorded entirely in Audacity with broken gear and no outside collaborators, went on to win the 2025 Polaris Music Prize—a quiet but powerful reminder that meaningful work can emerge from modest circumstances. These 16 tracks of self-performed songcraft marked a turn from his earlier sculptural approach to something more direct, condensing folk, R&B, country, blues, and Americana while channeling the homespun pop spirit of McCartney's II. What makes it even more striking is that, just a year earlier, he was at one of the lowest points in his career, unsure of his path forward.

Since then, his life has changed dramatically. The strength of the record earned praise from NPR Music, Pitchfork, and Esquire, brought new opportunities, new collaborators, and eventually led him to stages alongside Olivia Dean and Glass Animals—milestones he approaches with the same grounded, hard-working mindset that shaped the album in the first place. Now comes a deluxe edition of the album, expanding on the vision that took Jarvis from three-time Polaris long list nominee to winner.

We spoke shortly after the release of this deluxe edition of All Cylinders, a moment that offered a natural pause to look back on how far he's come. His story isn't about sudden hype or overnight transformation—it's about perseverance, quiet craftsmanship, and the unexpected ways a DIY record can reshape a life.

Arina Korenyu: You've said that this album made you no longer simply a recording artist but a songwriter. What made you embrace that title?

Yves Jarvis: For most of my catalogue, I never really thought about individual songs. I always thought in terms of albums—how to shape a full world from start to finish. The songs were just the pieces I used to build that world, and I didn't focus on them on their own. I was world-building, reflecting, and doing a lot of introspection. That's a big part of songwriting, but I wasn't thinking about craft or arrangement. Everything came from impulse, almost like keeping an impressionistic diary.

A lot of my earlier material isn't very singable either. With this record, I wanted hooks—not just production hooks but melodies people could actually sing. I wanted to return to more traditional songwriting, where a hook sticks with you and carries meaning.

And I want to keep moving in that direction. I'm not a traditional person by nature, so engaging with tradition doesn't feel like simplifying—it feels like leveling up. Traditional songcraft is just another flavor, another root system, another conduit for the work. My studio process is so experimental and patchwork that nothing I do will ever be purely traditional anyway, so adding this dimension only expands what's possible. It's just the next step.

Also, before this album, touring and performing never influenced what I made in the studio. I was always alone in that reflective, insular space. This time, hearing audiences respond in real time started to shape what I wanted to create. I wanted the music to translate differently—to speak a more entertainment-oriented, more outward-facing language. That shift made me think about arrangements and songcraft in a new, more intentional way.

Arina: It's also been mentioned that all sixteen tracks were created entirely by you, not even one outside contributor. What was empowering or challenging about working fully solo?

Yves: Working alone has always felt empowering to me. Any time I collaborated in the studio, I learned a lot about myself, but I rarely ended up with the results I wanted. The conversations, the compromises—they made things less malleable. I couldn't bring ideas to life exactly the way I imagined them.

My process has always been very character-driven internally. I draw on different sides of myself—almost like five recurring voices I return to musically, vocally, or through certain lyrical motifs. It pushes me to stretch in every direction.

But now, with what I'm making next, I can feel things shifting. It connects to this new focus on songcraft. I'm starting to crave real outside voices—to build a world that isn't only rooted in my own introspection. I want to work with people I trust, people who share my artistic language. That's how I want to break new ground on the next project.

Arina: How did limiting your tools to an old laptop and bare-bones software influence the outcome?

Yves: I used Audacity on Good Will Come to You, and honestly, I've used Audacity for almost all my records. The difference is that All Cylinders is the first album I made without recording anything to tape. In the past, I always tracked things on a four-track—either cassette or quarter-inch reel-to-reel—then brought everything into Audacity to sequence and overdub. The foundation was always analog.

This time, there was no analog in the recording stage. Things were processed analog during mixing, but the recording itself was done directly in Audacity—no plug-ins, no hardware.

That's part of why I haven't always been able to think of things as songs. I come from that Brian Eno school where the studio is the instrument, and the process is about sculpting and layering. I'd build textures by stacking parts instead of developing songcraft. I might layer four takes of the same guitar part just to make it sound like one well-recorded guitar. Those are studio tricks people use even when they have the gear—I just had to rely on them because I didn't.

My limitations have always been technical ones. I don't really know how to produce in a formal sense, and I've never had proper hardware. Most of my records were made with broken gear or the most basic tools imaginable—never anything studio-grade.

I always wished for that higher fidelity, but the creative limitations of having someone else in the room—feeling misunderstood, unable to delegate, unable to communicate exactly what I want—made those technical sacrifices feel worth it. I've wanted someone who could make my music hit harder, but I accepted missing out on that when I chose to work alone.

Now, though, I'm ready to expand the sonic palette. I'm starting to work with new people, and I'm learning so much—especially from seeing how they approach engineering on a technical level. It's already shaping my ear differently, and I'm excited to break new ground with that.

Arina: Leading up to the recording of All Cylinders, you mostly just listened to Frank Sinatra. What about Sinatra's clarity resonated so deeply for you?

Yves: I used to have a bad habit of shutting myself off from certain music because of strong cultural associations. I'd decide something wasn't ‘tasteful’—usually based on production choices or aesthetics—and that would make me almost deaf to what was actually there. Those contrived sensibilities kept me from being open. But that's part of growing.

For example, I never thought I'd enjoy Frank Sinatra. Big band music in general never appealed to me—the instrumentation, the brass. Not that I dislike all brass; Miles Davis is one of my favorites. But the way big band music is often produced would get in my way, and I couldn't really hear it. Once I got past those barriers, though, I found myself genuinely enjoying Sinatra.

What helped was having a kind of stepping stone. For me, that was his album Watertown. It's not really a rock record, but it does use electric guitars and more rock/pop-style arrangements. It's also a concept album, so it stands apart from the rest of his catalogue. That separation helped me appreciate what he actually does. I love Burt Bacharach, and Watertown reminded me of that kind of songwriting. From there, I started to recognize Sinatra's strengths—how good a storyteller he is, how theatrical he is, the emotional weight he brings. It really hit me. After that, I listened to his entire catalogue for a year.

That's interesting because I've never been a big fan of storytelling in music. My influences were always more postmodern—Talking Heads, for example. I've been revisiting Fear of Music, listening to how David Byrne writes lyrics, and Eno as well. That whole era of approaching pop by cutting it up, reassembling it, and keeping a sense of detachment—that was huge for me. I've always operated from outside the tradition, looking in.

Detachment has been a big part of how I've made music up until now. But lately I've been trying to do the opposite: to be integrated, to be at the center of the story I'm telling. Sinatra was the beginning of that shift for me.

Arina: What does receiving the 2025 Polaris Music Prize mean to you personally and artistically?

Yves: It feels great, especially because I'd been nominated a few times before. There are the ‘long list’ and the ‘short list,’ and I had made the ‘long list’ three times. The first time it happened was a huge deal—I was basically just out of high school, nineteen years old. Back then, the prize felt like it represented the more established side of the Canadian music world. I don't remember seeing many DIY or underground acts in the mix. Even if the nominees weren't major stars, they still had some connection to the industry.

So, when I got that nomination, it felt like they were really reaching into the underground, and that meant a lot. I had the same feeling when I won this year. It's not something I brag about, because ultimately people care about the results, not how the work got made—but I'm pretty sure I was the only person on the entire shortlist who made every part of the record alone: every instrument, every bit of production, all the writing, one hundred percent.

It's not that I expected to win, but I do try to make something ‘bulletproof’ every time. I aim for that level with each record. So, winning is surprising and humbling. When you make something entirely yourself, for the right reasons, purely for the music and the art, it means so much when people recognize it. And this one takes me back to that first nomination—being lifted out of the underground, not because of hype but because of the strength of the artistic statement.

That matters deeply to me also because I made this album at one of the lowest points in my life, at least in terms of stability. I'm a homebody—I need a setup, a space. But while making All Cylinders, I didn't have a stable place to live. I was couch surfing, moving through three different cities before ending up back in Montreal. Most of the album was made here, but always in transition.

On top of that, both of my previous record contracts had ended and weren't renewed. So, the year before the win, I was totally independent. I had the album finished, but I didn't even know if it would be my album. I was shopping it around, trying to find a label, a manager—everything. And then, without me really knocking on doors, people started coming to me because they'd heard the record. That alone was incredibly affirming. And then the prize came on top of that.

Arina: Did your tours with Olivia Dean and Glass Animals also come after this?

Yves: Yeah, that's the thing—I feel incredibly lucky to be working with the people I'm working with now. I have a great agent, and they were the ones who set up both of those shows. The Olivia Dean tour was especially wild—easily the most last-minute tour I've ever done. I got the offer a week before it started, which was insane.

The Glass Animals shows have been amazing, too. I'm used to touring and playing live, like I said, but I'm learning a lot. There are so many things I used to get away with that I simply can't do anymore. I used to perform without even bringing a tuner. I never changed my strings, never maintained my guitar at all. Now the stakes are higher—bigger shows, bigger audiences—and I'm realizing how crazy it was that everything somehow always worked out before.

Now I'm playing shows where my whole rig sounds better than it ever has, and I'm excited about this new frontier on the production side. I'm becoming aware of everything that goes into making a show sound rich and consistent. And all of that is feeding back into the music I'm making in the studio. It's reshaping my ear.

It feels like everything is growing. Everything is moving upward.

Arina: Lastly, what are your next big plans, and where do you see your songwriting going afterwards?

Yves: I'm definitely working on an album. I'm trying to change the way I develop music. I used to spend a year just working on instrumentals before even touching the lyrics. Now I'm trying to write the lyrics earlier and actually get songs across the finish line sooner, so the album can take shape in a more song-focused way. I also want to be able to perform the songs while I'm still developing them and bring what I learn on stage back into the arrangements.

The album is in progress in a way my albums usually aren't. I have a handful of songs that are already finished, and I'm bringing them into the studio to get help from other people with arranging and recording. I'm also recording alone in studios with gear I've never used before—gear that just sounds better—which changes everything. It's suddenly easier to get the sounds I want, so the playing feels more natural, more expressive.

Lately, I've been doing these long days—ten or twelve hours—just making music nonstop. I'm really excited about what's next, and I'm hoping to have something out early in the new year.

I love the feeling of anticipation, but I also know how fast culture moves now. Even though my process has always been pretty isolated and slow, I don't want to disappear for long stretches anymore. I like the idea of having a more reactive relationship with culture—releasing music much closer to when I actually make it. That's the goal for the new year. I'm not sure exactly what it will look like yet, but there will definitely be new stuff very soon.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmMiguel Angel Bustamante

The TonearmMiguel Angel Bustamante

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

Comments