They say never to meet your heroes. Well, I met Adrian Sherwood. Though this was only a video chat meeting, Sherwood was warm and welcoming, launching right into our conversation with an open rapport. He was sitting on a comfy couch in his studio space, a large window behind him displaying the London dusk. He asked the first questions: where I was calling from, seemed sincerely interested in what it's like here, and empathized about my eyes (I had apologized for squinting, the effects of a recent procedure). Sherwood, seasoned by decades of journalistic inquisitions, was immediately casual and spontaneous. I could have been seated on an equally comfy couch right across from him.

I suppose I could call Sherwood a 'hero.' My mixing desk aspirations were heavily influenced by the man's expertise at touching the right knobs at the right time, often resulting in a sparkling starburst of sound. His early work is the stuff of legend—production stints with the dub-infused likes of Creation Rebel, New Age Steppers, and African Head Charge, all mainstays of his fabled On-U Sound imprint. But take a look at his production credits on Discogs (539 entries so far!) and you'll find his fingers all over the innovative edges of British dub over the past four decades. There are curious outliers still enhanced by Sherwood's rub-a-dub, such as all the electronic 'industrial' forebears—you know Sherwood worked on some of the first music by Nine Inch Nails and Skinny Puppy, right?—and then those as far afield as Sinead O'Connor, Panda Bear, and Spoon. But dub is the unifying force (indeed, the unifying force, some might say) and reggae is the idiom where that force blossoms in Adrian Sherwood's busy hands.

With all that time spent mixing and producing others' records, Sherwood is unsurprisingly less prolific as a solo artist. The last album solely bearing his name, Survival & Resistance, was released thirteen years ago. So The Collapse of Everything is a big deal, an Adrian Sherwood album of ominous dub vibrations, where the tempos are generally slow but the message is bright and clear—I and I, on the verge of collapse. It's a personal work, defiantly studio-constructed as Sherwood grieved the loss of collaborators Mark Stewart and Keith LeBlanc. The album's third track, "The Well is Poisoned (Dub)," identifies the world view, one that is frustrated and disappointed with how On-U's idea of cultural unification hasn't caught on with the world at large. It's a song that's rigid and cranky, studio alarms and explosions booming through a swamp of instrumentation and a beat that's worn down from all the fighting, yet ultimately comes off as resilient. There's still On-U's trademark humor found in titles like "Spaghetti Best Western"—nodding to Morricone with love and an endearing obviousness—and the squelchy low-riding skank of "Dub Inspector." The experimental reach peaks on "Spirits (Further Education)," all stereo effects and sparseness, hinting with hesitation at the oncoming revelation that awaits us all.

In a previous email interview with The Tonearm, Sherwood told me he finds the dub audience "perhaps leaning towards caring about the planet a lot more than most human beings." Thus, this album rewards that community with sounds straight from the source of On-U, drawn through decades of collaborative tales and gallons of compressed air blown into crackling mixing desk faders. Sherwood's tried and true techniques have grown into widescreen atmospheres that flow like a film score, and he expressively translates personal loss into a universal meditation on collapse and renewal.

Sherwood was genuinely engaged in our conversation, and my notes were set aside early on as we proceeded to geek out about the art of using the mixing desk as a musical instrument. The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Michael Donaldson: This album, The Collapse of Everything—man, I really like it a lot. It strikes me as somewhat inward-facing, and I don't mean that in a negative way. Contemplative and ruminative. Does that make sense at all?

Adrian Sherwood: I was just trying to make something that was sonically representing where my head's at. I've reached a certain age, and I wanted to create something that I could play out during live events, but also something that you could listen to at home, and it would trip you out. I've been embracing all the new technology, the new plugins, and all the wonderful new outboard equipment being made. So, I've literally just made a record to please myself, to be honest, and I wanted it to be quite melodic and also jump out of the speakers at you. I'm very happy with it.

Michael: Are you creating songs as a way to test out the new gear?

Adrian: I always test it out. Because I'm not a proper musician, I'm always pushing to make the gear feel like it's breathing, bleeding, or pulsing. I've also used a lot of old techniques, such as overdrive and EQ sweeps. And I wanted to make sure I was happy with the bass lines. I worked very consciously on every bit of the sonic just to draw the listeners in to where I wanted them, and how I wanted it to be heard.

It's difficult to talk about making music without sounding like a pretentious idiot. That's what I always find interesting about doing interviews, chatting about, ”Were you consciously thinking that, or were you thinking this?” Basically, I embarked on the recordings three years ago, and I've done a bit here, a bit there, waiting for someone to contribute. Then I worked in a condensed time to finish it. But I've got to say, it doesn't sound like somebody else's record. That's what I did. I wanted to make something that bears repeated listens and can also function as a stoner's album. And some of the tracks I can play out and shake a building with. That's what I was trying to do.

Michael: So was this tracked live, because I assume you're tracking musicians, and then you have a separate mixing process?

Adrian: Yeah. I make the basic rhythms, but then I overdub live players, so nearly all the performances on the record are live. The drums were live—we might have ended up putting them on a grid, but they were largely live. So was every single ingredient on it. But because of being able to work on a grid, you're able to process, work with the tunings, and do little treatments on every bar if you want to. I was working to try and make a good groove, while also using all the dub sensibilities I have. And then, the final thing, when I've recorded everything, I use some plugins during the process. Then I'm attacking the final mix. Some tunes are much less subtle than others, but I did it quite subtly; in certain tunes, I wanted things to leap out at you.

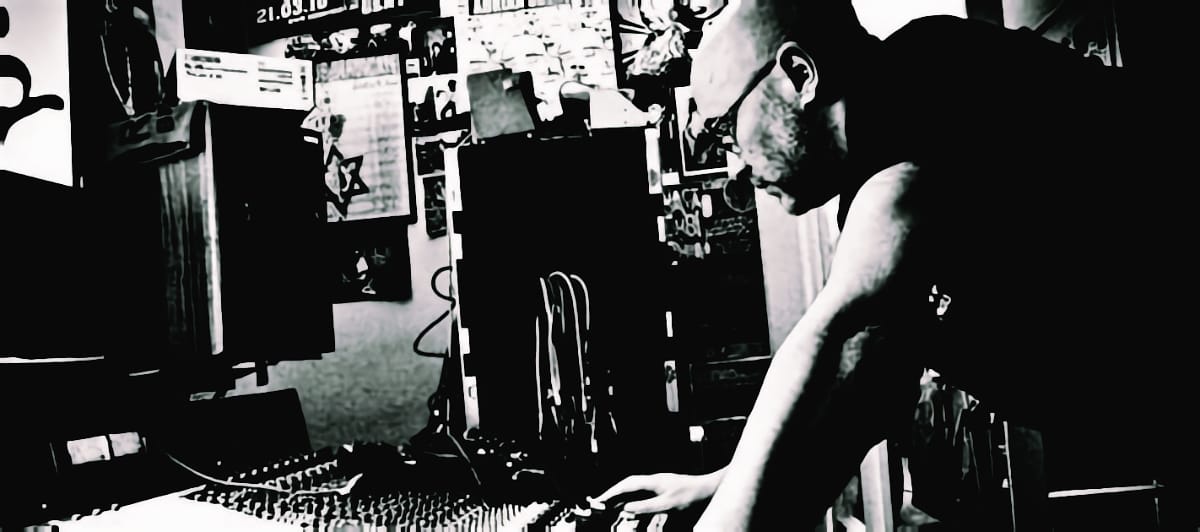

So that's the process. I'm always finishing it, doing an analog mix with my hands. And that's a little bit of a dying art. But I advocate that, and I think anybody who plays with live mixing and can get to do that really gets the interplay.

Michael: Absolutely. I also come from a background of working with a large mixing desk. I had a studio partner back in the early nineties, and the most fun we had was standing over each other and bumping elbows, both of us playing with the desk as the tracks were going. The desk can be like an instrument if you do it properly.

Adrian: And also, when all the musicians have done their thing and you've recorded, if it's your time, then start. So what I tend to do is when I've got it where I want it to be, I'll then do maybe three mixes, and I might end up saying, “Oh, I like mix one,” or mix three, or whatever, or a combination of the three. And then I might even add overdubs to the final mix on some occasions. But generally, I'll do three mixes and occasionally edit between them.

What I don't like is when you listen to records and you hear what's about to happen next. You go, “Okay, one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight. Something's about to happen. Here we go. Something's about to happen.” I've obviously got that on my stuff, but I'm trying to get it so that other producers, musicians, and people can't quite hear the formulaic, boring old shit going round and round again. And I consciously work on it, having things come ahead of the one, crossing over, and just to spin, swing, and trip you out so that you're dancing a little bit from the hips as well as nodding your head. I want it to be quite a psychedelic experience.

Michael: I've heard that what draws a lot of people into music is the anticipation of what's going to happen next, and then that being fulfilled. But then throwing off that anticipation with a surprise is what creates that ‘tingle’ in the listener.

Adrian: I think with my stuff, a lot of people like it because it has elements of surprise. The early things—when I was learning, I always wanted that myself. So I'm not just having surprises for the sake of it, but—now with the control that you've got, and obviously getting older and not trying to prove a point or something or make it hard, like industrial-type things, I'm trying to make the elements of surprise pleasing ones. You know as well as I do that the drop has been the exciting thing in dance music for two or three decades now. The drop got longer, and the drop was everything. And I think with reggae, the sound systems, as well as the clubs, it was extreme trebles dropping down to extreme basses. And we all love that.

Michael: So I imagine, partly from my experience, but just from what I know about from listening to what you do, that the mixing process and playing the board is pretty much all intuitive. It's almost like an improvisation.

Adrian: To a point. I'm on the studio floor of the house here. There's a studio a couple of rooms back there, and that room has got loads of equipment, like the great Cinema Engineering EQ or the Langevin. Then I've got M/S reverbs and EMT springs, and those are used on almost everything, so I know what I'm going to do with them on any mix I'm working on. And I do plan them. I deliberately don't write at a desk. So I've got twenty-four channels, and I know that one is bass drum, two is snare, three is high hat, four and five are toms, and so on. Before I actually launch into a mix, I learn where I've placed everything. Then I look at the meters, and I become one with the mixing desk, like a little octopus, adding and bringing in those effects. And by that time, I'm really in control of it.

But I do know it needs to be pushed. I then have in my head how to take it and make it appear as if it's coming from behind the wall or behind your head with reverb sweeps. And then the other key is understanding the anti-production. So when it's all really wet, you just suddenly dry it with reverbs and delays, then pull it right back and hold it for a while to create a little bit of healthy tension. And then maybe EQ something into a machine to make it swoop away, mix things out so it's really empty again, and then let it drop down. All those things I plan, literally just a few bars ahead, like you're playing musical chess a little bit in the mix. I can hear what's needed, and I've got the references to know how to do it. That's not my ego or anything speaking. That's just what I've learned from decades of practicing and doing it. And even on gigs, I attack mixes when I'm doing live bands, which I don't do very often anymore, but I love doing. You want that element of surprise and mischief and fun, and all the things that I like are those things instilled in me by the likes of Lee "Scratch" Perry, who's like a naughty child and wanted mischief and fun in his sound and didn't want it to sound like another person's work.

Michael: Do you feel like you have essentially the same sense of intuition as far as knowing what to do with a mix—when to pull out, when to bring things in—as you did when you were mixing in the early eighties?

Adrian: In the early eighties, I didn't know what I was doing. I was overloading the desks, mixing to tape that I overloaded as well. You could do a lot in those days with tape and saturation; if you want to do that now, you might have to plan differently. For example, I can emulate tape saturation by using overdrive—a cheap TC EQ, driving the input, overloading it, and then turning the output down. That's a really cheap, simple way of doing it. You can buy one of those machines for 150 bucks. But in the old days, I might have achieved those results by using tape. But now if I'm doing things like the tape saturation, I'll have to do that using a tactic similar to the one I just described.

I've learned so much in those forty-odd years that I sometimes find myself watering down something that needs to be radicalized a bit more. Sometimes, as you get a bit older, you become a bit set in your ways. I'm trying desperately to surround myself with new people who threaten and push me, rather than just saying, “Oh, that's really good.” That's not what I need. So I push the mixes, push the productions, push things. And luckily, I've got a good set of people who will say, “God, I hate that,” or “I love it.” You don't want to be in some middle thing where it's ‘okay,’ because that's never going to get any results.

Michael: It seems to me that you've always had that attitude of wanting to push yourself or put yourself in different or uncomfortable situations. You move yourself forward with all the genre-hopping you've done your entire career.

Adrian: I started with the Jamaican stuff. Reggae was my love, but from very early doors, I got invited to do work with Depeche Mode, Ministry, and on and on. They always got me in to do the weirder side of things. But you know what? I'm just grateful that I had my head opened up early by my friends, Mark Stewart, and others, and was introduced to new ideas. Working with The Fall, for example, I learned things—no effects, nothing—and how to create a healthy tension in the production using no effects, just the actual acoustic sound of instruments. So I'm very blessed. I've worked from great funk—the great American friends of mine, Doug Wimbish, Keith LeBlanc, and Skip McDonald—to African, Jamaican, folk music, jazz, and everything else. I've applied similar techniques. I learned about the use of tonality and space, and I've applied it to everything I've ever done.

Michael: There was one release you produced several years ago that I really liked—it was a Japanese trio with a hard-to-pronounce name.

Adrian: Nisennenmondai.

Michael: Oh, that was fantastic.

Adrian: They were great. That album was like using almost anti-production techniques. I was just capturing what they did, recording it properly, letting them play. I was adding little bits. I was using a Binson Echorec disk delay, the Italian one, and some very old effects, and it just seemed to work perfectly. We made that whole album in three days. Brian Eno really likes that album.

Michael: There's a live performance for Boiler Room that I listen to as much as the album. It's so good. So very tight..

Adrian: Yeah, they were great. They all had babies. We were due to do another album, and we did a tour together. Then one by one, they all fell pregnant, and that was the end of Nisennenmondai.

Michael: Speaking of albums, I have to ask about the title of the album that brings us together today, The Collapse of Everything. I was going to play clever and ask, “What is everything?” But of course, everything is everything.

Adrian: Yeah, I just thought it felt very appropriate. A lot of people feel like that at the moment. They feel very scared and sad. But also, when everything collapses, you get to rebuild. So it's not all negative. I just thought it fit the times we were in. That was all.

Michael: There’s the song title "The Great Rewilding." I suppose we could view ‘rewilding’ as a positive, or it could mean that the humans are gone.

Adrian: Yeah. Also, the meaning of the last track, "The Grand Designer," could be anything. It could be God, it could be interpreted any way you like. But at the end, it’s an instrumental record mainly. I wanted to challenge myself, and I'm going to be doing this live. And I'm going to be coming to America in March for the first time in many years. I'm not going to be able to do it as a band thing, but, for the first time, I'm going to be building a studio on stage with my engineer out front from the studio here. I hope people like it.

Michael: I was actually going to ask about that. I see you're playing Big Ears, and I plan on attending, so I'll see you there. What are you traveling with for the live set? A mixing desk?

Adrian: I'm going to have a thirty-two-channel Midas desk on stage. I'll have sixteen channels coming from a computer hard drive, so I'll have bass drum, snare, high hat, toms, percussion, bass, guitar, all the parts of an hour's worth of music. I'll also have a couple of CD players and an SPD noise pad, a noise machine, for making dub noises. I'll have three reverbs, three delays, and a parametric equalizer. And I'll be mashing the stuff to pieces throughout the whole set.

Michael: Excellent. So you're excited about this.

Adrian: Yes. I think Big Ears is the first event. I'm not sure. I want to go there and reconnect with a lot of people, like yourself, as well as older individuals who are aware of what I've done, and try to make some new, younger fans as well. Obviously, as the years pass, you want to get a load of new ones, as the others all get old and decrepit and don't go out. But it’ll be good to see everybody. So I'm very excited. And I'm looking forward to representing, because it's been a long time. We've dealt with all the costs of work permits and whatever, and I think we'll be doing ten shows between the States and Canada.

Michael: Excellent. Speaking of 'ears,' how are your ears? How do you take care of your ears?

Adrian: My ears are okay. I had a little issue with my left ear, but that goes back to when I burst an eardrum. I got an infection from my daughter when she was a kid, but they're working pretty well, I think. Touch wood. I think my hearing's pretty good still. I like hearing things very loud or very quietly. I check everything on different speaker systems that I can trust, and yeah, they're not too bad.

Michael: So, do you protect them in any way?

Adrian: No. (lauighter)

Check out more like this:

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments