In a dusty corner of the internet just over two years ago, I stumbled across a brief Reddit thread in r/LetsTalkMusic on the day Ethiopian nun and pianist Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou died. Someone had posed the question: How did you first find the music of Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou? The answers were telling—fragments of discovery scattered across continents: a late-night radio broadcast, the sudden appearance of her piece "The Homeless Wanderer" on a recommended playlist, and even as the unlikely backdrop of a Walmart commercial. Her music often seems to find you, rather than the other way around.

The eventual discovery of Emahoy's work and history was laborious and complex, a credit to the original crate diggers with ears to the ground, unearthing lost tapes and offering up their untapped audio treasures to eager listeners worldwide. It would have been easy for Emahoy's music to have disappeared into obscurity—had French musicologist Francis Falceto not somehow found her music in the early 2000s, we would have lost a precious and pious discography to the aether.

How does that translate to contemporary discovery? Has the advent of the algorithm helped us re-find otherwise lost music? The infinite scroll of suggested songs means we can never "finish" streaming sites—we're chronically rooting out gems, exhuming long-gone, obscure, and hazy unknowns from times gone by. Every now and again, they'll resurface online, celebrated posthumously in esoteric corners of the internet. Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou materialized for me in such circumstances—a popular streaming site suggested "The Homeless Wanderer" to me through their generative "radio" function, which led me, in turn, to a plethora of Ethio-jazz greats. I'm thankful, in truth, despite my disdain for artificial suggestions of intelligence. Emahoy's legacy will now endure long after the record plays out.

Dancing across Ethiopian pentatonic scales known as kignits, the sonics native to Ethiopia are distinctly different from Arabic maqams or Indian modes, with Emahoy's own sound intertwining with the tenets of a far-flung Western Romanticism found in her early musical education in the rolling hills of Switzerland. The four main Ethiopian kignits known as anchihoye, tizita, bati, and ambassel form a loose base for Emahoy's music, building a sonic identity that shares a kinship with both her locality to Ethiopia and an experimentation of her own musical explorations and experiences far from her home in the bustling hub of Addis Ababa.

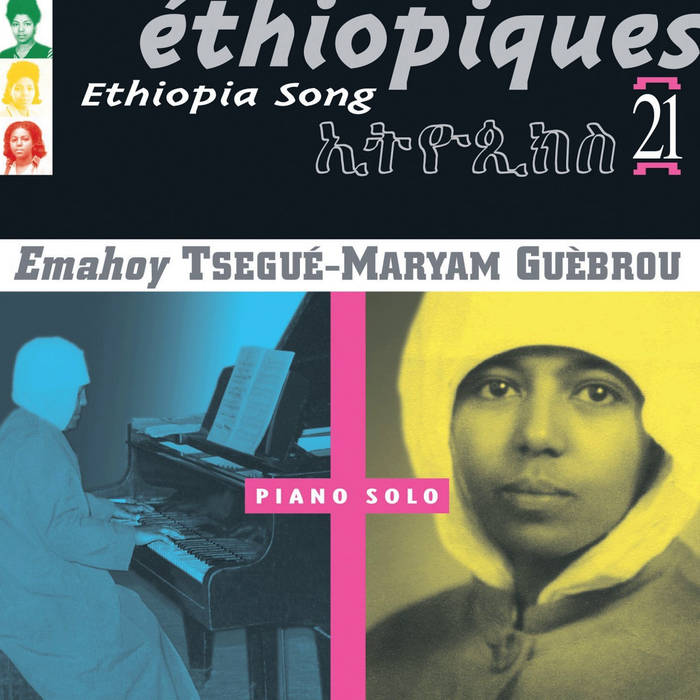

The fusion of fin de siècle parlor piano, gospel, ragtime, Ethiopian folk, and Orthodox choral traditions becomes clear following the history of her expansive ninety-nine-year lifetime, with writer Ted Gioia penning a piece in the year before her death exploring her resistance to pigeonholing by genre. "There is no genre for funky Ethiopian nuns," shares Ted, and I can only agree—Emahoy is often loosely situated in the widely celebrated genre of Ethio-jazz, brought to light by French musicologist Francis Falceto and the Éthiopiques compilations, of which Emahoy was featured in 2006, but we're listening to something vastly different from clean-cut jazz, or even the more relaxed capsule of free jazz. Instead, we're observing a sound that draws from all four points of the compass, with Ethiopian folk traditions playing as vital a role as her European classical repertoire.

Emahoy's precision is clear and distinct, despite employing a notably free and easy rubato tempo, with what could begin as a waltz often ending in a markedly different 4/4 time signature, more than likely shifting time mid-piece. Stylistically, Emahoy developed a catalogue of techniques, with her crisp piano trills replacing a more bluesy key slide, as if bending the pitch without altering the clarity of the note. This flourish feels reminiscent of Baroque ornamentation, with her own melismatic, circular melodies inspiring a peaceful coexistence of melancholy and joy in her music. "Sadness was always next to me like a friend," as Emahoy once said, a quiet lament to her own history and expression over a near century of life.

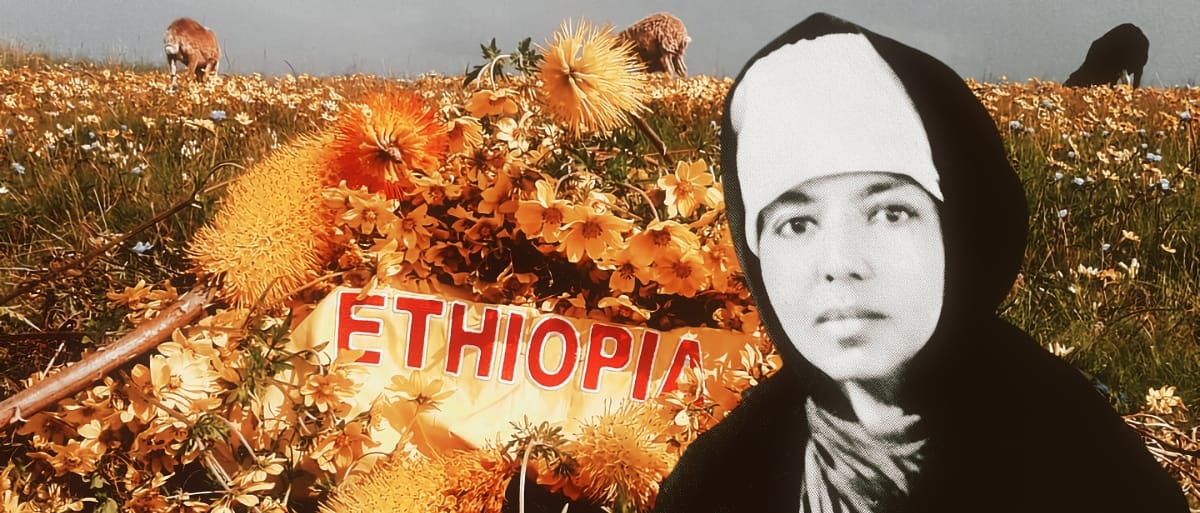

Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou album covers through the years, via Discogs.

Born in 1923 into Ethiopian high society, Emahoy's given name was Yewubdar Gebru, meaning "the most beautiful one" in her mother tongue of Amharic. Her father, Kentiba Gebru Desta, was a respected diplomat and mayor, while her mother, Kassaye Yelemtu, moved in high society and was closely related to one of Emperor Haile Selassie's wives. The family was wealthy and part of the Amhara clan, a community from the Northern Highlands of Ethiopia that speaks their own language, providing a privileged and upper-class upbringing for Emahoy and her siblings.

Emahoy's early life was one of luxury, and at six years old, accompanied by her sister, Senedu Gebru, the pair was sent packing to a Swiss boarding school, making them the first Ethiopian girls to be educated abroad. Handed a violin and bow and sat in front of a piano, Switzerland was Emahoy's first exposure to European classical music and jazz, marking a shift in her playing and listening that echoes back far later in life. Returning to Addis Ababa as a now grown-up and glamorous young woman after her schooling, Emahoy marked yet another first by becoming the first female civil servant in Ethiopia's history, working for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as well as singing for Emperor Haile Selassie.

In 1935, the second Ethiopian-Italian war broke out, with Mussolini at the helm of the violence that conquered Ethiopia, leaving Emperor Haile Selassie exiled, and Emahoy and her family arrested and placed in a prisoner of war camp on the Italian island of Asinara, which continued into Mercogliano, a city adjacent to Naples. Throughout the conflict, three of Emahoy's brothers were executed, a devastating loss closely followed by the Second World War, after which Emahoy swiftly moved to Cairo.

Studying with the highly respected Polish Jewish violinist Alexander Kontorowicz in the oppressive heat and dry terrain of Egypt, Emahoy was playing violin and piano for countless hours each day. Despite a clear love for her musical studies and extensive practice, Emahoy was overwhelmed by the height of the heat and returned to Ethiopia with her teacher, now fluent in seven languages and a highly proficient musician with a deft hand to match.

Finding herself struggling as a musician in a country with no classical music, let alone female classical musicians, Emahoy turned to her piano, instead composing music for herself in the absence of an audience. Soon after, Emahoy was offered a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music in London, but permission from Ethiopian authorities was denied for reasons still unclear to this day. Heartbroken, Emahoy refused to eat for twelve days, accepting only sparse cups of black coffee. Despite a rushed hospitalization and the last rites being performed to her by a concerned priest, Emahoy didn't die. Instead, she decided to become a nun.

"It was His will," declared Emahoy, a religious epiphany that, at the tender age of twenty-one, led her to join the Guishen Mariam monastery as an ordained nun in the mountainous hills of Northern Ethiopia. Living barefoot and firmly rooted to earth, or perhaps more likely heaven, Emahoy was given the religious name "Tsege-Mariam" and the title "Emahoy," which means "female monk" in Ethiopia. Despite her love for music and extensive training, her newly found hermit life required her to abstain from music except for church plainsong. "No shoes, no music, just prayer," she once said. After ten long years of no electricity or running water high up in the mountains, Emahoy fell ill and eventually left the convent, returning to the comfort of Addis and the welcoming arms of her family.

Back in the capital in the early 1960s, Emahoy found herself studying Saint Yared's liturgical music from the sixth century, the composer and father of early Ethiopian religious music tradition. Throughout this exploration and study, Emahoy's composition style shifted notably from classical to more blues-inspired, with the "complex phrasing" featured in her first record released in 1967 demonstrating a delicate fusion of Romantic piano and Ethiopian sacred modes.

In 1974, power was seized in Ethiopia by the Derg coup, a Marxist-Leninist military junta that overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie and hastily ended his forty-four-year reign and the ancient Ethiopian monarchy. Emahoy's first vocal works, Souvenirs (1977–1985), were recorded in the cloak of night due to restricted church liturgy access, with songs like "Ethiopia My Motherland," "Clouds Moving on the Sky," and "Don't Forget Your Country" exploring nature, displacement, and the waning national pride amidst the "Red Terror." Upon listening to Souvenirs, the ambient sounds of open windows and birdsong fill the room. It's a private recording with the illusion of expanse, and, I find, deeply moving.

As the years bore on, Emahoy was threatened with arrest by the Ethiopian military dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam because of her religious beliefs and convictions. As her mother had sadly passed and left her with no remaining family ties, she fled to Jerusalem, where she returned to her religious life, living in Debre Genet (Sanctuary of Paradise) Orthodox convent situated squarely on the corner of Ethiopia Street. Taking a vow of poverty, Emahoy's room was home only to a piano stacked with tapes and manuscripts, an altar to her life's work, a catalogue of over 150 works for piano, organ, and chamber ensembles that musician Maya Dunietz worked hard to finally publish in collaboration with Emahoy.

Years later, French label Buda Musique launched the Éthiopiques series, documenting Ethiopia's golden age of pop and jazz from the late 1960s to mid-1970s. A scene known as 'Swinging Addis,' this era was a lively fusion of traditional Ethiopian kignit scales, Western jazz, American soul, and the bright ring of funk. The Éthiopiques series featured major Ethiopian artists including Mulatu Astatke, Alèmayèhu Eshèté, and Tilahun Gessesse, with French musicologist Francis Falceto discovering a lost album of Emahoy's archived recordings in 2006, which went on to be released as part of Éthiopiques Vol. 21. This compilation was dedicated entirely to Emahoy, and brought her international acclaim as a meditative, genre-defying "honky tonk nun," later known as the "Piano Queen" in Ethiopia. Scholars like Thomas Feng studied her annotated scores, calling her rhythm "elastic" and her phrasing "prayer-like," a perceptive assessment of her genre-free sound and rhythm. Emahoy was alive to see her success, a pocket of dedicated listeners spread far and wide, much like her scope of influence.

On March 26, 2023, Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou died in Jerusalem at the age of ninety-nine. At her funeral in Kidane Mehret Church, her piano was played in tribute, a final gesture towards a life spent at the instrument. Friends say she wrestled with the unanswered question of what might have been, had she been allowed to study in London, but her legacy lies precisely in what she made of what she had.

"We can't always choose what life brings," she once said, "but we can choose how to respond."

In her music, that response is clear: a patient, unhurried devotion, and a close meeting of melancholy and joy. To hear "The Homeless Wanderer" now is to hear her life's story refracted through sound—exile, prayer, resilience, and transcendence.

Éthiopiques 21∶ Ethiopia Song from Bandcamp or Qobuz and listen on your streaming platform of choice.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmMiguel Angel Bustamante

The TonearmMiguel Angel Bustamante

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments