Simultaneous Contrast is the first profile album of composer Lila Meretzky, released last June on Sawyer Editions. Meretzky is a composer from New York City writing instrumental, vocal, choral, electroacoustic music, and music for dance, film, and installation. Meretzky is also a dedicated music educator specializing in creative music making, musicianship, and music theory.

The album is a distinctive artistic statement from a young composer, an embodied music with soft edges and large contrasts, an endless variation of repetition with a particular focus on rhythmic juxtaposition. There are five pieces on the album with differing instrumentations and durations. There is an emphasis on works for percussion—three of the five tracks have substantial percussion writing, two of which are percussion solos.

The title Simultaneous Contrast nails the artistic vision of the album: Meretzky's work has striking divergence in multiple musical layers. Track two, "Chaconne," for solo singing percussionist, is a flowing exploration of different timbres—a memory of a song, a lullaby where the singing and the playing drift from each other into independent lines. The first track, "Quartet," for a quartet of strings with percussion, evokes watching the ocean in moonlight, like an instrumental interlude in an indie rock album that spins out into its own energy.

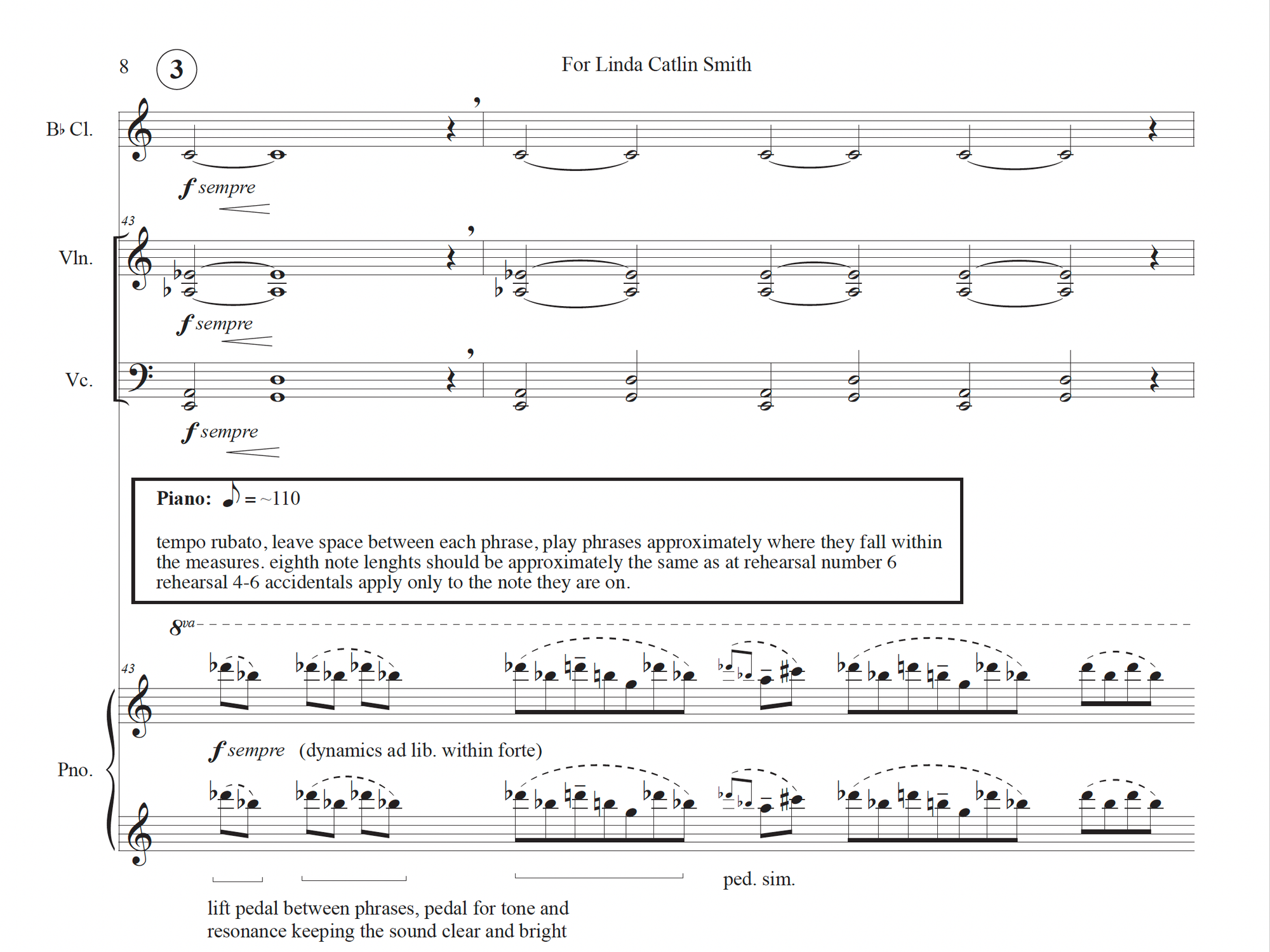

For me, the highlight of the album is "For Linda Catlin Smith," performed compellingly by the Unheard-of//Ensemble. The large beginning section of the composition for clarinet, violin, and cello has an alluring drift that hypnotizes the listener while building in momentum and intensity. When the piano finally enters the piece, the contrast in tempo, harmony, material (a kind of singing, bird-like melody), and color is an injection of unexpected flavor into the palette of the work. In every work, the simultaneous contrast is palpable and captivating. Meretzky has a talent for large shifts in texture that surprise the listener and then converge and evolve in an absorbing way.

"To crave and to have," the only string orchestra work on the album, showcases Meretzky's talent for composing for large instrumentations. It's easy to imagine her building a prominent career as an orchestral composer, and I hope to hear more of her orchestral work released in the future.

Meretzky spoke with me about her work from her apartment in New York City in July 2025.

Chaz Underriner: Tell me about how you decided to become a composer as opposed to a performer, and how you had that binary in your mind. What were the things that you were first interested in or wanted to explore more when you started writing music more seriously as a part of your life?

Lila Meretzky : I think I had a lot of grand illusions about what being a composer would mean, and I feel like it's been a process that continues today of closing the aperture and figuring out, “OK, I'm not going to write my Symphony No. 1 on the first day that I sit down to write. It's actually going to have to be a two-minute piano piece, and then my friend is going to read it. And maybe not even that is going to be successful, but it's going to give me an idea about the next thing that I have to do.”

What I can remember about the very beginnings of my composition study, when I was working just on my own, I think it came from a place of wanting to, as many teenagers do, express my angst and my feelings about things. And I think in a lot of ways that's what's become fun about composition for me. It actually quickly became clear that it's about maybe getting away from yourself and exploring things outside of your own emotions and using musical material as a vehicle to create stuff you wouldn't be able to create with your conscious mind.

Though I think at the beginning, when I was writing process music, repetitive music, a kind of minimalistic Steve Reich film class-inspired stuff, where I'm just going to spin this top, set it in motion, and see where it takes me. It's going to be so much more compelling than if I sat down and tried to write an art song about how I'm feeling today.

Trying to get away from your own subjectivity and self is something that continues to interest me. On the one hand, it's impossible—everything that you do, that you put your name on, is coming from you. There's no way to get around that. But I think of music less as a form of self-expression and more as a form of discovery, generally, or an attitude towards engaging the world around you.

Chaz: I think I've had a similar experience in artistic work, being sometimes really subjective and sometimes pushing outside of the self. That's a fascinating aspect to making art, and everybody approaches it differently.

Lila: It's always been a strange negotiation between these: the idea of making something that's personal versus something that's more abstract or impersonal. A lot of the ways I think about my music are abstracted from what the end result will be or what the emotional impact will be. But a lot of the feedback I get is that it feels like very emotional music, very personal music.

I think about a piece that I made in my sophomore year of college ("A Long Journey Finished"). And this honestly might be my favorite piece of music that I've ever made, even though it's clanky and junky in terms of the way I made it. When I was in college, my dad wouldn't really call me on the phone, but he would send me these long emails, and he sent me this beautiful email recalling the death of his grandparents when he was a kid. And I was really affected by this, about the fact that we struggled to talk about these things, but it was so effusive when put into writing.

Without thinking about it, I recorded myself reading the email on my phone. And then I put it in Audacity, and I made these weird little kind of fake banjo sounds, and, without really anticipating what the end result would be, just stacked them on top of each other. The pacing of the reading and of the letter happened to flow really well with the music underneath.

Then I played this three-minute fixed media for the weekly recital at my music school, and it was so weird taking such a personal thing and exposing it to everyone. But it was also abstracted because it goes from my father's thought into a written form, into my recorded voice memo, into this weirdly processed sound world. And then it's not even played live. I'm just standing there with my phone, a very impersonal method of sharing music with other people. But it turned into an emotional experience. I think it was very disarming for a lot of people who listened to it. Probably pretty uncomfortable. That was a formative moment for me.

I also realized that it's difficult to see outside of what you're doing and how what you do is going to come across to other people in a completely different way. Perhaps it's better to release your attachment to what the final experience will be like, even though it's important and is part of what makes the piece.

Chaz: Absolutely. I often don't know what my pieces are about or what they're really doing until after I've watched or listened to recordings of them years later.

Lila: Yeah, and I think about it in relation to the album—the oldest piece on the album is from 2018 ("Don't look for me where birds sing"), the percussion piece. I think the meaning of it changed for me a lot when put into juxtaposition with some of these newer pieces.

Chaz: In the album itself, I didn't realize that piece had a tape part in it. So I was just listening, and all of a sudden, there's this vocal part that comes in. I went and read the program notes and read that there was a fixed electronic track, but it kind of gets to the idea of simultaneous contrast concept, which I think is a really great title for this album because it's something that you're doing a lot creatively. And I see that also happening in your visual work when you're doing collage.

I feel like every piece explores some aspect of juxtaposing elements that relate in an abstract way. So, can you talk about that approach to composing with simultaneous contrast?

Lila: Simultaneous contrast is a term referring to the afterimage in visual perception. This sort of visual illusion, where if you look at an American flag for thirty seconds and then you look at the wall, the red stripes are green and the white stripes are dark.

I came across this idea of simultaneous contrast in an art class that I was lucky to take at the Yale School of Art, which was called Color Practice. It comes from the teaching of Josef Albers, who was a very influential artist in the twentieth century. He was a student at the Bauhaus and then a teacher after he left Germany during World War II. I have my copy of Interaction of Color here, and I think all composers should at least take a look at it.

The whole point of this book and Albers's approach to color pedagogy is that the elements you think are stable colors are actually entirely unstable and depend on their context, and are very flexible. So, you do all these exercises with pieces of colored paper, where you have to turn two different colors into three different colors by placing them on backgrounds of different colors and experimenting with the size and shape of the cutouts.

I really loved the idea of using stable elements and making micro-adjustments to yield sometimes shocking and visceral changes to what you're seeing. I felt that there were some parallels with the music that I already liked. I think I have a natural penchant for really strong timbral contrasts and the contrast of sound materials.

When I came across this term in class, I tried to think about bringing that into my music in more intentional ways. I wouldn't really say that there's a one-to-one in the music process as it relates to color studies that you do if you're working through this book. But I loved the idea that you don't have to reinvent the color green; you can actually just move it a little bit. You can make the shape smaller, you can try a different shape, and you're going to generate this whole new experience with your material.

Not to pathologize it, but when I'm working, if I try to get too ambitious, I'll get overwhelmed really easily. So for me, especially at the beginning of the compositional process, I like to be really meticulous, and I'm just going to change this one note, or I'm going to do this whole thing again, but a little bit softer. And what happens then? Is it interesting? It's so far yielded music that is pretty repetitive, but if you listen closely, there's never actually repetition. Something is always changing.

It's something I came across two or three years ago, but I realized it was something that extended back further into my work. Like this piece "Don't look for me where birds sing," I'm doing this drumming. What happens is suddenly out of nowhere, without any anticipation or forewarning, this voice comes in. I think that relates to this question of "what if?" that I love when I'm composing.

The idea of simultaneous contrast also has a metaphorical meaning for me (and this might be a bit of a stretch), describing the relationship between "art/dreaming" and "real/waking life." On a personal, spiritual level, making art gets me closer to a 'dream world' where certain things that are not possible become so: revisiting the past, preserving memories, speaking to the dead, slowing or stopping time. "Don't look for me where birds sing" embodies the simultaneous contrast of parallel worlds on multiple levels. There is the contrast of old/existing music in the song that's quoted ("mayn rue plats"/"my resting place") and the new music that I wrote, the acoustic/electronic contrast. There is also the contrast between the robotic repetition in the percussion part being the live, flexible element, while the expressive and vulnerable/non-metric vocal part is trapped in a fixed medium.

Chaz: And whenever I listened to "For Linda Catlin Smith,” was that a string trio, or is there a clarinet? I really couldn't tell because it's recorded and mixed really subtly. But then the piano comes in, doing its very distinctive thing that's really different from the clarinet, violin, and cello. Then I realized, this is the classic instrumentation of Olivier Messiaen's Quartet for the End of Time! But I couldn't even tell until you started using this contrast technique.

Lila: I had a very formative experience listening to that piece live when I was in high school. It's cool to eventually write for that instrumentation, even though in many ways it couldn't be more different.

Chaz: And to me, it's great to do this using two different media, like an acoustic instrument and adding in tape that comes in suddenly, but I think it's even more powerful when you're doing it just with instrumental writing, like a lot of tracks on the album. Then you're using the same sonic materials but with such a big contrast. You said earlier that you feel like you still need to work on the basics, but whenever I listen to your music, I get a sense that you really know what you're doing with basics like rhythm, harmony, and texture. And you can do that really with just the instruments playing notes.

For someone like me, an intermedia artist, I have a hard time creating that much contrast within just one artistic medium. So I think that's a real strength of your work to be able to do that kind of thing in acoustic music.

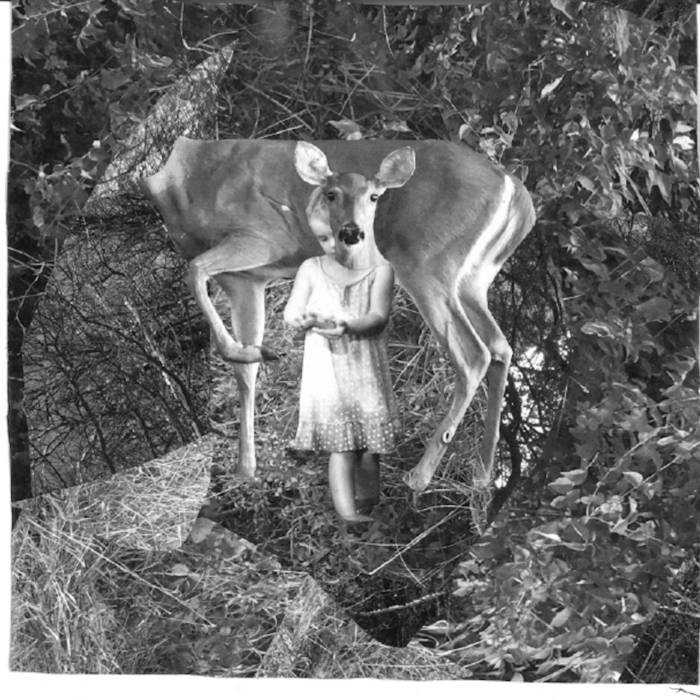

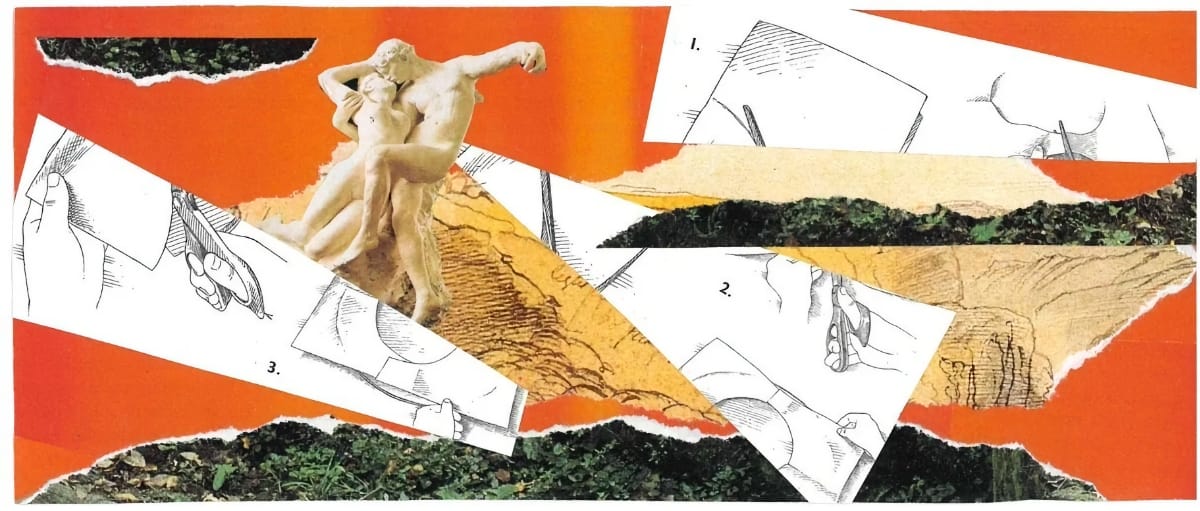

Lila: That's a really nice thing to say. Since I started making visual art during the pandemic, I was kicked off campus in my last semester of college, and I was sitting in my mom's house, not doing any of my schoolwork, not turning my papers in, just killing time while she was out being a nurse, like literally alone for six months. I started making hundreds and hundreds of collages, and now I'm not doing them quite as feverishly.

Constructing them back in those days, I learned a lot about trusting the artistic process and making automatic art, which I think has been instructive for my music-making. But I've never really brought them together in a fully integrated way. And that's something that I feel a little insecure about because there's so much great intermedia art I've seen recently, and it's something that I almost wish I could do. But maybe there's nothing wrong with having these kinds of parallel tracks or keeping them separate.

I would love to find a way to turn collages into graphic scores or make a score with collage, but I haven't really scratched the surface. I would have to do a lot of studying before I could start doing that.

Chaz: Can you tell me more about how sound and visual arts are a part of your life?

Lila: I've always been a little bit jealous of people who say that music is therapeutic for them. I don't find that to be true. It's very stimulating and fulfilling in many ways, but I wouldn't say that it brings me a lot of comfort. Other people's music does, but maybe not my own music. I think that the visual art is a meditative thing for me. It's time when I'm not looking at my phone, when I am truly engaged in something just because of the sensory pleasure of it. It's something I'm not trying to monetize.

I have collages on my website, but it's nowhere near comprehensive. These are just scans when I'm done with them. I would say that I'm less serious about it than music and that I don't have a kind of formal training, but it has been five years of pretty regular practice of doing this. I wouldn't say I'm totally directionless. I look back on what I do, and I can tell that I have certain tendencies: I really don't like putting human forms in the collages. They're very abstract. I don't think of these collages like magazine collages that you do in art class for elementary school or whatever.

They have a tendency to be funny or surreal, but not in a conscious way. But looking back on what I do, they aren't that funny or surreal in terms of, "Oh, I put an elephant on a tiger's body," the easy things you can do with collage. So yeah, it's almost like exercise or reading. For me, it's a hobby, but I'm pretty deep in it. And I think that it has a lot of benefits to my life in the part of my creative practice that I'm trying to professionalize, which is music. I guess the difference is that I have no long-term aspirations with it. Whatever I do is the point of doing it. Whereas music, I want to release more albums. I have pieces of mine that have been performed, but I want to revise them and record them, and turn them into more albums.

I'd love to write an opera someday; I have a long-term vision for what this part of my artistry will look like. But my visual art is a bit more spontaneous and less ambitious.

Chaz: I'm interested in what you said about music being really stimulating and not therapeutic to you, whereas making collages is more of a meditative practice. Have you ever tried to use composing or any form of music-making as a meditative practice?

Lila: Sometimes, but for me, that's an idealized way of engaging with it. Often, you don't want to work on something, but you have a commission. You're not in the mood, but it's due in two weeks, and you have to spend X number of hours in order to get from point A to point B.

But I do feel like I've achieved a sense of flow, meditation, and maybe emotional relief when making music. For example, the tape piece I made using my father's letter was very cathartic. I also perform—I'm a singer, a pianist, and a very bad accordionist. I perform with two choral ensembles in New York, and that is an important part of being a composer for me—finding ways to have musical experiences that I'm not the main part of, where I'm subsuming myself and being a part of this collective, trying to work on my musicianship skills and my sight singing skills, tuning, and my ear. But also having fun in a social environment. I don't want it to sound like music is painful; it's not always, but I can't just tap into this river of music every single day. Maybe if I didn't have a full-time job, I could.

Chaz: I think composing is usually difficult, and I don't talk to a lot of people who are like, "Composing is easy and making music just comes to me naturally."

I’d like to ask about your studies. Particularly since you finished your graduate degrees a couple of years ago, I'd like to hear about who you studied with and how your work was shaped by those conversations you had.

Lila: In undergrad, I had a teacher who was very influential to me, this guy named Stan Link. We haven't been in touch recently, but he encouraged me and instilled in me the idea that "you don't have to invent everything." In other words, discover the things that you can, go out into the world, and just play with music, and whatever arises from this playing, you can edit and refine later. But the first and most important part is generating this music that nobody's ever heard before—getting into the music and playing around with it. And being very un-self-conscious and trying to separate the generative phase and the editing phase of your work. I don't always—sometimes the cycle starts to spin a little bit too quickly, and I get into the editing phase too soon, or I over-edit. But I think that's been an important piece of wisdom for me that I still feel is useful, even though my music has changed a lot from that time.

And then when I was in grad school, I rotated around with all the teachers at Yale. I got exposure to pretty much everyone there. I think that something David Lang once said to me was, "Why do you have this transition in your music? Let's just be in the piece; we don't need to transition. You don't need to preface what you're about to say, you don't need to account for it, or apologize for it. What happens if you just go there and say the thing you're most excited to say from the get-go, without having to prop it up musically in another way?" It's not like a strict law, but hearing it said in such an extreme way was pretty striking to me in terms of saying, "OK, you know what? It's OK to cut large parts out of your music. Let's trim the fat and get to what you actually care about here."

Chaz: And do you feel like, with those words of wisdom from two different teachers, you find yourself connecting with those ideas whenever you're working now?

Lila: Yeah, I think about it. I think about both of those things pretty frequently. I think sometimes I would like to play with musical transitions. Maybe there's a better way of putting it—a faster rate of change that I can push myself to do. Someday, I would like to write a piece that's all transitions, and swing hard in the opposite direction.

Chaz: Is there anything else you want to talk about?

Lila: It's interesting looking back. The benefit for me of doing an album is having my music exposed to more people and experimenting with the format of the album and curating it, figuring out the order. It's given me a lot of reckoning of, "OK, what is this music that I've made in the last five years?" It's weird calling something a portrait album. You look in the mirror and see something that's backwards from what everyone else sees. You're never really able to perceive yourself in an objective way. Doing something like this album makes me feel like I want to do something really different next time.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmChaz Underriner

The TonearmChaz Underriner

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments