Sara Jayne Crow on Brian Wilson's Sanctuary

There's a world where I can go and tell my secrets to

In my room, in my room

In this world I lock out all my worries and my fears

In my room, in my room

Do my dreaming and my scheming

Lie awake and pray

Do my crying and my sighing

Laugh at yesterday

Now it's dark and I'm alone

But I won't be afraid

In my room, in my room

In my room, in my room

In my room, in my room

The plucky harp and saccharine vocal harmonizing intro of "In My Room," one of the Beach Boys' most commercially successful songs, exhibits the inherent paradox in so much of Brian Wilson's music production. It's beautiful and sad. It's about the internal, but so external. It's innocent and experienced. The song was written to underscore the solitude Wilson sought in the sanctuary of his music studio—the only place he found satisfaction, despite the house perched atop the crest of the Hollywood Hills, the stable of Maseratis and Rolls-Royces, closets of the toniest barkcloth Hawaiian shirts, walls of platinum and gold records, and the entourage of hangers-on attending to his whims. The vicissitudes dominated. Wilson spent decades traveling from the pinnacles of charting records and thankless tours to valleys of obesity, unrest, drug abuse, and mental instability. The paradox formula looks something like this: Wilson wants solitude, seeks the studio, makes a hit—and doesn't get solitude.

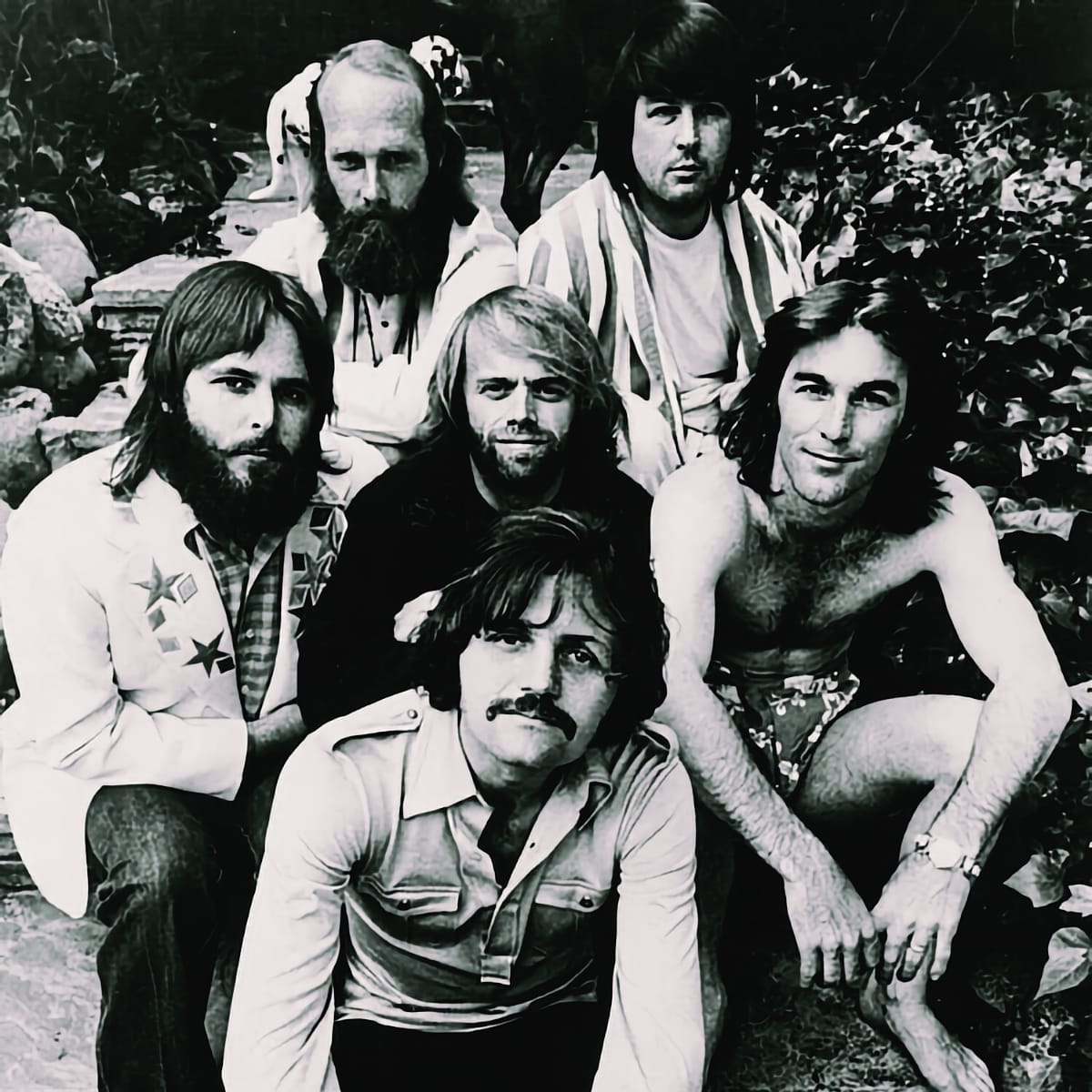

Wilson's trajectory with music began at age eight as he started tinkering with the piano. He formed the band the Pendletones in 1961, his senior year in high school (the name being a take on Pendleton button-down shirts), with his cousin Mike Love, friend Al Jardine, and brothers Carl and Dennis Wilson. The group would go on to form iterations such as Carl and the Passions and Kenny and the Cadets before being christened the Beach Boys in something of an accidental moniker for a record label. The first singles were all girls, surf, sunshine, brawn, revving engines, and testosterone-fueled adolescent thought bubbles: "Surfer Girl," "Judy," "409," and "Surfin' Safari." These songs ratcheted up Billboard charts: the first album, Surfin' USA, held the number two album spot when Surfer Girl was released just months later and climbed to number seven, followed in quick succession by Little Deuce Coupe. Wilson and the Beach Boys worked tirelessly through 1963 and 1964 in recording sessions comprising nine- and ten-hour shifts. The teenagers were manipulated by record executives riding the tsunami wave of the surf trend while lining their own pockets. Towheaded sunny dispositions notwithstanding, the precocious Beach Boys became acquainted with cynicism at a very young age.

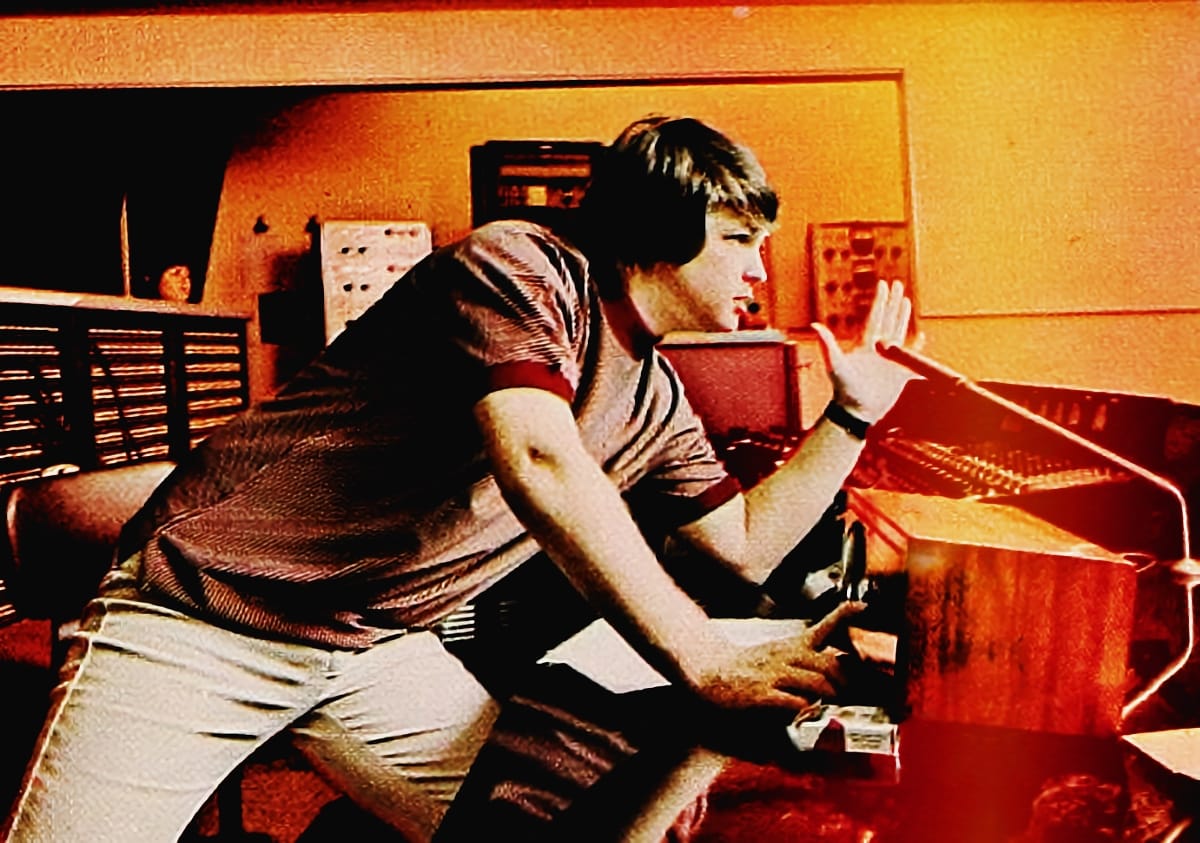

Wilson says of his music production in his memoir, Wouldn't It Be Nice: My Own Story, "My method of writing hasn't varied much since [the] early days. I start by banging out chords, searching for catchy rhythms, usually beginning with a run of boogie-woogie. I play until all sense of time and place is overcome by the music, until I'm lost, until the left, logical hemisphere of my brain slows down. From within those trance-inducing rhythms spring notes, then snippets of melody that seem to jump out of thin air. If I'm lucky, I catch 'em."

In the solitude of Wilson's room, his music production was something of a salve for his personal demons. "It was a compulsion," he said in his memoir. "If I didn't write, I didn't function properly. I was wracked with worry and anxiety. I didn't sleep. I suffered bad dreams. . . . I loved playing as a way of entertaining people, but I also played in order to separate myself from the world. As an abused child, I learned my playing kept my dad at bay. It drew people to me, made them like me, and at the same time, I didn't have to deal with them." Wilson's compulsion to escape was rooted in deep psychological unrest. Following a traumatic childhood of physical and mental abuse by his father and attendant silent acquiescing neglect by his mother, he spent several decades in the spotlight suffering from undiagnosed schizophrenia and manic depression. He heard voices in his head.

Wilson's main impetus for creating music was to escape these voices and replicate the melodies only he could hear. This culminated with Pet Sounds, an album lauded by critics but mostly ignored by radio and the charts. Despite this, the Beatles' Paul McCartney told Rolling Stone that the album was required listening for his children.

Following Pet Sounds, the "Good Vibrations" single was something of an opus. While Wilson was under extreme pressure from other members of the band and the record label to offset lukewarm sales amid critical accolades, Wilson wrote "Good Vibrations" as a "summation of [his] musical vision, a harmonic convergence of imagination and talent, production values and songwriting and spirituality." Wilson initially wrote the song as "a grand, [Phil] Spector-like production while on [an] LSD trip." The song was recorded over seventeen sessions and cost between $50,000 and $75,000 (in 1966, mind you), featuring parts from Glen Campbell and numerous other session players implementing bass, clarinet, harp, cello, and even the Moog theremin.

Around this time, the public's fascination with the blond and blue-eyed California surf sound was beginning to wane. The rosy disposition, revelry, and daisy chains gave way to opposing forces begat by Vietnam terrors, and the Beach Boys' five-year domination of the charts came to a close. Hendrix's shrieking guitar was more representative of the collective agitation. In 1967, Hendrix proclaimed the death of surf music at the Monterey Pop Festival. Wilson says in his memoir, "By then, the fast-paced music world's interest in the next Brian Wilson release had been supplanted by other, bigger and hipper events" like the Festival. The lineup included (initially) the Beach Boys along with Eric Burdon & the Animals, the Grateful Dead, Buffalo Springfield, Simon and Garfunkel, and Jimi Hendrix. The Beach Boys decided not to perform because "next to the electric rock of Hendrix, Big Brother and the Holding Company, or Country Joe, the Beach Boys suddenly appeared out of it." During Hendrix's performance at the legendary event where the Beach Boys were conspicuously absent, he "foreshadowed the hard times ahead when he hissed to the crowd, 'You'll never hear surf music again.'"

Perhaps it was the end of surf music. During the ensuing decades and until the 2013 Grammy win for Best Historical Album (oddly, the Beach Boys' only Grammy coup), countless Beach Boys records were released without much fanfare. The somewhat successful song "Kokomo" was released in 1988 on the Cocktail soundtrack, a blip on an otherwise silent radar. Wilson had no involvement whatsoever with the song. It was written by Terry Melcher, John Phillips of the Mamas & the Papas, Beach Boy Mike Love, and Scott McKenzie.

In sixty-three years, Wilson has endured opportunistic and malicious forces from all directions. He lost most of the hearing in his right ear after his father, Murry Wilson, hit him with a wooden plank. Murry circumnavigated the courts for many years to siphon royalties after years of serving as the band's tyrannical manager. Brian spent three years locked in his bedroom between 1972 and 1975 in a bout of agoraphobia. He finally sought therapy through therapist Eugene Landy, who dominated his life and business decisions for many years and was finally barred from contacting Wilson by court order. Wilson even endured numerous lawsuits from his own cousin, bandmate Mike Love. He has endured strife throughout the decades with grace and aplomb, bouncing back from three-hundred-pound obesity, rampant cocaine and alcohol abuse, divorce, agoraphobia, and any number of other setbacks.

For a brief period following the release of the acclaimed film biopic Love & Mercy, Wilson thrived in what Rolling Stone touted "one of rock & roll's most unexpected and astonishing third acts." Wilson's courage and resilience inspired John Cusack, who portrayed Brian in the movie, who said, "He's incredibly tough, like, motherfucking, seriously tough. He's not perfect. But he's healthy and happy, and he's making music, and he survived. Michael Jackson didn't make it. Elvis Presley didn't make it. Brian made it."

When describing the process of recording his 2015 album No Pier Pressure on The View, Wilson explained that for the first time in his life, he felt no pressure to make music. So, finally, music doesn't have to be the crucial escape "In My Room" as it once was. Perhaps Wilson finally found the sanctuary he so desired. His paradox formula may now resemble this: Wilson wants solitude, seeks the studio, makes a hit—and gets solitude, perhaps in his final rest. He's earned it.

Michael Donaldson on His Life with Pet Sounds

My Bloody Valentine's "Blown a Wish" is the shoegaze "God Only Knows." Are you with me? The gorgeous layers of vocals meticulously placed in a sea of sound (as opposed to the Wall of Sound), a flowing, watery state that swells in the ears and ebbs in the heart. MBV's Kevin Shields has spoken a lot about the experience of Pet Sounds. This profound influence may have struck the early '90s college rock crowd as unlikely rather than inevitable. But inevitable it is—if you're making records while swimming in the waters of the sounds in your head, you've no doubt been doused in the influence of Pet Sounds.

Brian Wilson's work and experimentation extended before and beyond Pet Sounds, but that album is overwhelmingly ordained as ‘the one.' That's the case for me. I was about six years old and growing tired of my Peter Pan 45s, so I asked my mom for a "grown-up" record. She pulled out her small vinyl selection and let me pick. Fortuitously, I chose Pet Sounds. I'm pretty sure the reason was that the Boys were feeding cute animals on the cover. What a way, at the age of six, to make one of the best musical decisions of my life.

My mom later confessed that she bought Pet Sounds for "God Only Knows" but was a little flummoxed by the album as a whole. That was apparently the common reaction at the time. But for my untrained six-year-old ears, the album was a warm transmission, perhaps the much-talked-about childlike nature and curiosity of Brian Wilson speaking directly to a curious child. I loved it all and listened endlessly. I think I understood the idea and sequence of the album—I appreciated the "come down" instrumental title track at the end (with that great guitar line and tremolo effect) and especially the sounds of a train and a barking dog that concluded the magic. That stuff brought me to some other world, which I now recognize as Brian's world.

I still have the original album that I listened to repeatedly as a kid. I left it behind when I went to college and temporarily became a part of the college rock crowd. Years after that, upon moving house, my mom found it in a random box and asked if I wanted to have it. Hell, yeah! The LP is now framed and hanging on my office wall. Here's a photo:

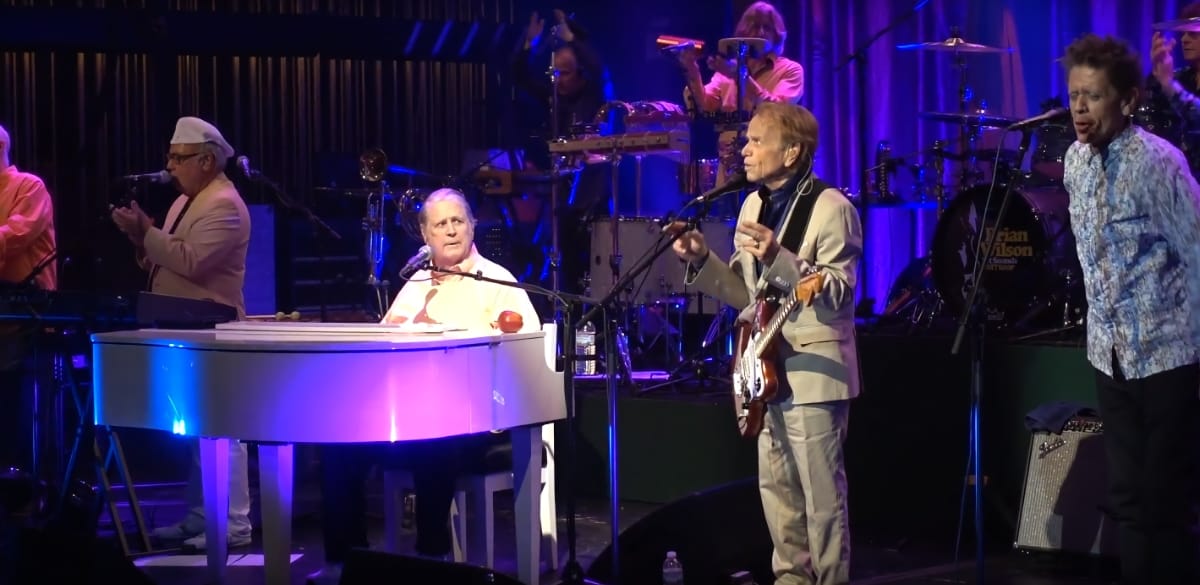

In 2017, Brian Wilson embarked on the Pet Sounds 50th Anniversary World Tour, joined by longtime Beach Boys Al Jardine and Blondie Chaplin. I had never seen Brian in person, so I jumped at the chance to attend the Orlando date. I also invited a special guest to join me. At the time, my aunt-in-law, Toni Tennille, was living in Orlando while working on her memoir. Along with her late partner, Daryl "the Captain" Dragon, Toni was a member of the Beach Boys touring band a few years before the Captain & Tennille became mid-'70s superstars. With Toni in tow, our small crew watched and enjoyed the run-through of Pet Sounds and the flurry of preceding hits. Brian was ragged, raw, and sometimes distracted—much has been said about his onstage demeanor—but it was such an emotional charge to see him in action. Brian was also clearly enjoying himself. The stage was as much his element as the studio.

Toni didn't know what to think. Her memories of those times, times they were all made for despite statements otherwise, were suddenly clouded with melancholy. Toni's interactions with Brian were limited (he was out of the touring picture when she and Daryl were in the band), but still, seeing Brian up there was evidence of what remains after the flood of the passing years.

As for me, I joined the audience in clapping along to Brian Wilson’s 'pocket symphony,' "Good Vibrations." When the breakdown approached, anticipating the tempo change, Brian abruptly shouted into his microphone, "Stop clapping!" I turned to Toni and happily exclaimed, "I can't believe I just got musical direction from Brian Wilson!"

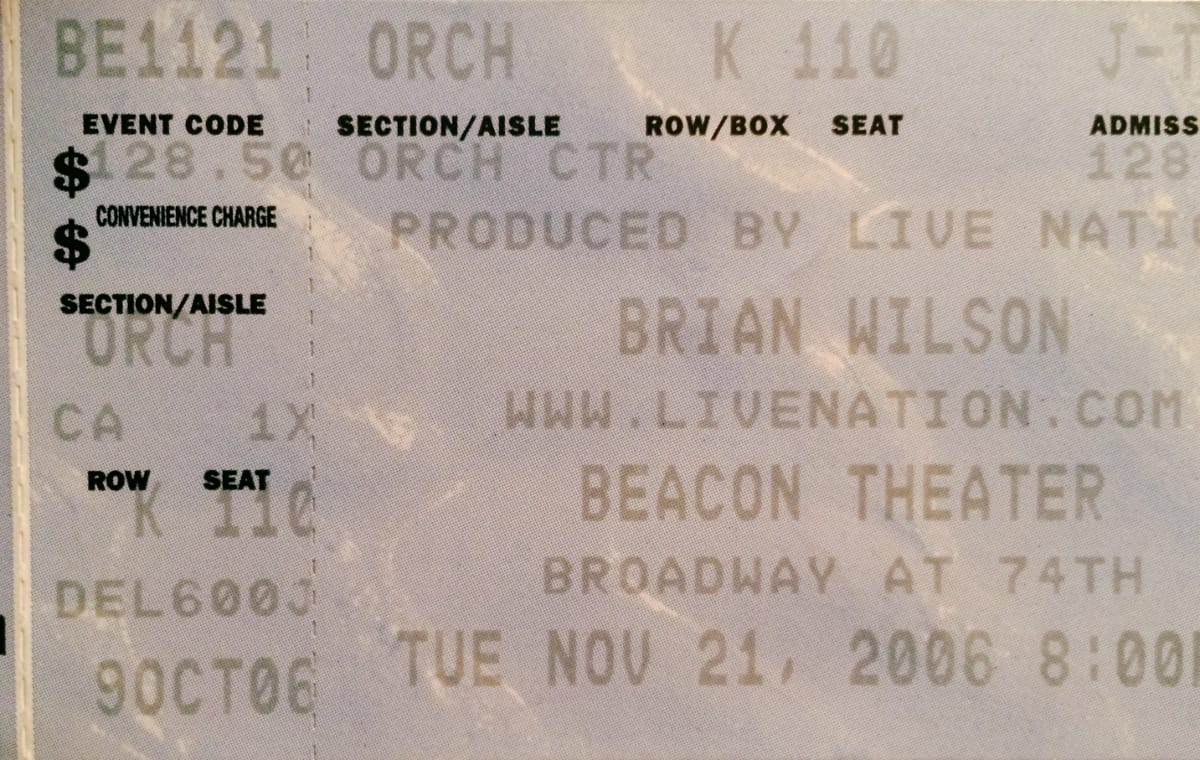

Lawrence Peryer's Journal Entry from November, 2006

Have you ever lost someone you love? Been betrayed by someone you trusted? Been so ill at ease that you couldn't leave your bed?

Of course you have, but all at once?

Brian Wilson has. The fact that he still manages to get on a stage in front of people, and sing the way he does, preaching the message of love and positivity that he does, is nothing short of astounding.

I went to this [the Pet Sounds 40th Anniversary Tour] with such low expectations, having been counseled that this was the only way not to be disappointed. I have heard a lot of mixed things about his shows—everything from "they are sublime" to "kinda sad, he gets confused." But the will, dignity, and soul I saw on display from that man had my face soaked with tears more than once, and I hoped the business associate I went to the show with was not looking my way.

Original Beach Boy Al Jardine joined Brian for most of the show, and his voice added so much. All night I had obsessive thoughts over and over about all they, but especially Brian, had been through. The catalog of heartbreak is staggering: abusive father, creative torment, the pressure of success, the drugs, the mental collapse, the exploitation by friends, family, and advisors, the death of brothers . . . and I thought more than once about my own tragedies, heartbreaks, and disappointments and how my life has been shaped by these events. Seeing his grace makes me ashamed now to give in to cynicism, irony, and self-pity.

I enjoyed the show despite the moments when his voice cracked or when he spoke awkwardly. Rather, this vulnerability in front of a roomful of people, no matter how adoring, was what made the show so incredible.

There were, of course, stellar musical highlights in the almost three-hour program: "Add Some Music" and "Do You Wanna Dance" were terrific. "And Then She Kissed Me" and "Sail On Sailor." Wilson was genuinely embarrassed by the standing ovation he received after "God Only Knows." But one has to wonder what goes through his mind when he sings that song. Or "In My Room"? To say nothing of everything else on the complete Pet Sounds.

Cool people do not apologize for being themselves. They don't try to impress anyone. They are deep. Authentic. Cool people inspire other people. They are vulnerable.

Brian Wilson is the epitome of cool. Believe it.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmWilliam Slyter

The TonearmWilliam Slyter

The TonearmR.U. Sirius

The TonearmR.U. Sirius

Comments