Jeff Parker isn't afraid to take on the work. Born in Connecticut and raised in Hampton, Virginia, the guitarist and composer studied at Berklee College of Music before moving to Chicago in 1991, where he joined one of the most fertile independent music scenes in the United States. He's played in Tortoise since 1996 and founded both Isotope 217 and the Chicago Underground Trio. A member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) and a prolific sideman, Parker has recorded with George Lewis, Fred Anderson, Meshell Ndegeocello, and Bill Callahan, and others.

His 2016 album The New Breed—his fourth solo release—marks a shift in his creative practice. The record merges his long fascination with hip-hop production (particularly the work of J Dilla, Madlib, and MF DOOM) with his background in jazz improvisation and composition. Working with producer Paul Bryan in Los Angeles, Parker assembled Josh Johnson on alto saxophone and keys, Jamire Williams and Jay Bellerose on drums, Bryan on bass, and played guitar, synths, and other instruments himself. His daughter Ruby Parker sings on several tracks. The result treats sample-based beat construction as genuine composition. Parker uses this method to merge written and improvised material into a single technique.

The album's genesis stretches back more than a decade. Parker spent years in the early 2000s studying the art of hip-hop, reading Wax Poetics interviews with Marley Marl and DJ Premier. He bought records for sampling and DJ’ed regularly around Chicago. Parker built hours of beats while trying to find what he calls "a zone where that approach translates to making a record." Parker then worked closely with Bryan on The New Breed to achieve this unified sound of sampled material and live performance occupying the same sonic space.

Jeff Parker was a recent guest on the Spotlight On podcast, where he discussed the origins of The New Breed. He also spoke with host Lawrence Peryer about the influence of Chicago's integrated musical scene, the differences between collaborative and solo work, and the tension between artistic ambition and the practical realities of making a living.

You can listen to the entire conversation in the Spotlight On player below. The transcript has been edited for length, clarity, and flow.

Lawrence Peryer: With this re-release of The New Breed, what's it like for you to return and revisit some of this material, especially given that you're a busy cat, always working, always creating. What's it like to reflect like this?

Jeff Parker: It's good, especially The New Breed. That record is very meaningful to me. I'm really proud of that record. It's kind of my favorite one. It's the first record where I feel like I put a lot of pressure on myself to make a record that wasn't collaborative.

Even my projects before that—Like-Coping, The Relatives, and Bright Light in Winter—they weren't like that. That trio [on those albums] was a band, you know? I put myself out front, but we were a band. Those guys wrote as much music as I did. With this one, it was me really stepping outside of my comfort zone. I realized that I could make my own music on that record, and I really liked it.

It feels a bit weird to say because you hear a lot of artists where they made something and they don't listen to it, they move on. All my records, I pore over them pretty hard, and I want myself to be able to like them. I want it to be something that I want to listen to. That's why I haven't made that many records, because I like my records. I like to listen to them. I don't listen to them that often, but when I do, I like to look at them and be proud of the work that I've done.

Lawrence: Last year, I spoke to Josh Johnson, and we talked a little bit about the role of Paul Bryan. Josh had said that sonically, Paul gives things a sense of space. But another thing Josh said was, "He keeps me from overworking things." Does that resonate for you in terms of having somebody give you at least some guardrails or some guidance? What was your dynamic and working relationship?

Jeff Parker: Paul is somebody I really like—very detail-oriented, technically proficient as a recording engineer, mixer, and producer. That was mainly my relationship with him. I had a specific sound in mind for The New Breed project for sure. That kind of took him out of his comfort zone. I wanted my things not to be so clean. I wanted them to be dirty. I was dealing with samples, sampling stuff from old records, and trying to get the ensemble playing to mirror this aesthetic or sound concept that I had from sampling. I wanted to try and bring the two things together so that when the listener hears the record, it's cohesive in that way.

Paul is great. We both learned a lot in the projects that we did.

Lawrence: You've talked in the past about how The New Breed sounds like Los Angeles. How conscious are you about place?

Jeff Parker: Not so much about place geographically—it's more about the communities that you create, the interactions that you make. With The New Breed, I've had the idea for a long time, like decades, before I was actually able to be in a place where I had an infrastructure where I could make that music. Paul had a home studio that he offered to me and his technical expertise. I had the music and met musicians out here that I wanted to collaborate with.

If I had made The New Breed in Chicago, it would've been completely different. I would've been involved in a different community, and the aesthetics that that community of musicians had would've worked their way into that album, and it would've sounded completely different. It's more about the community than the actual place geographically.

Lawrence: Yes, you can hear elements of that scene. It really does appear. It's not about a sound of Los Angeles per se, or trying to be a tone poem about Los Angeles, but you can hear what was going on.

Jeff Parker: I was aware of the beat scene out here, and one of the musicians who I had been fortunate enough to work with—one of the people I actually sought out when I got to Los Angeles—was Miguel Atwood-Ferguson. Certainly, some of that music from that scene was definitely working its way into the music that I was making out here, even though the skeleton for that music was all made when I lived in Chicago.

Lawrence: How would you describe the skeleton? Was it your idea to pursue beats and sampling?

Jeff Parker: Basically, that was it—just components and, as an exercise just to keep myself busy, I started to make beats from samples, just from being a fan of that golden era hip hop in the nineties—Tribe Called Quest and Pharcyde. Not having a technical understanding of that music, I started to just try and do it on my own. Sometimes I would try and recreate beats that I would hear on records. I would figure out the source material and then try and see what they were doing.

It was an exercise for me just trying to have a deeper understanding of that music and trying and figure out how to work it into my own music in some way. So I had hours and hours of beats, and I was working in a specific DAW called Reason, which was one of the earlier sample-based workstations. I just started to demo music in that.

My idea was—because I consider myself an improvising musician; my improvisation is based in jazz and bebop—I was trying to figure out a way to use my background in jazz improvisation and composition and arranging with making beats. That's essentially what it was. That's not anything new—people have been doing that for a long time—but my own take on it was what I was trying to get out there.

Lawrence: As you were digging in and learning about the production techniques, did you come to have a different appreciation for what producers like Dilla, Doom, and Madlib were accomplishing as you started to learn more about the ‘how?'

Jeff Parker: I already had a pretty deep reverence for what they were doing. I think the thing that I learned the most was how to incorporate it into my own music. It just expanded my palette as a composer. That was my goal—that's what I was trying to get out of it. I like to make beats and stuff, but I have so many other things to offer just as a guitarist and as a composer.

It's the same way—even as a jazz musician, I didn't really have any aspirations to learn jazz so I could regurgitate music from recordings. It's the same thing with hip hop—I was looking to deepen my understanding as an artist.

Lawrence: When I hear you say that, it feels like there's a contribution to a lineage going on. You're not trying to be a tribute band or regurgitate. It could be just one little brick that you're adding to the wall of music, or you could have your own little mosaic here in the corner. But it's this sort of never-ending story that the players who view it as a lineage really do get to contribute to.

Jeff Parker: I definitely look at myself as in a lineage of the musicians who mentored me, and the musicians I've studied. It's definitely a lineage. You want to contribute something—it's just creative energy, really, trying to put something positive out into the world. People hear your music, and then they carry it on.

Lawrence: Well, on the topic of lineage, tell me a little bit about the album title, The New Breed. There is a deeper connection to your life there, and I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that connection.

Jeff Parker: I was working on the material for the record, just making stuff, not really anything behind it. But my father passed away while I was making the record, so it kind of became a tribute to him naturally. It wasn't like I was like, "Oh yeah, I've got to make a tribute to him." It just became what I was dealing with in my life.

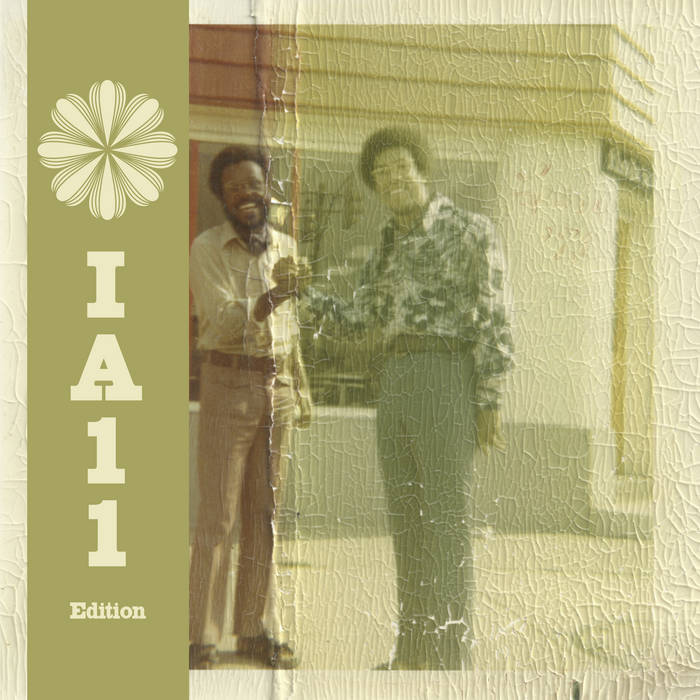

But he had, for a short time, owned an Afrocentric lifestyle shop called The New Breed. There was a very small chain of stores. I decided that I wanted to name the album The New Breed after the store. So I started to do a little bit of research about it, and I found out more about the chain. Then Scottie McNiece from International Anthem helped me to realize that visually—he was like, "Are there any pictures of your dad in the store or anything?" I reached out to my sister, and she found a couple of photographs around the shop, and one actually became the cover photo. It's the only photo of my father that I can find of him in front of the store. He's just giving a handshake to a colleague. That's the cover of the record.

Lawrence: I love how the photo carries the same aesthetic in a way as the music in that it doesn't look like it was digitally cleaned up. It's got an analog quality. I think a lot of the music sounds terrific, but it's not this pristine digital sound. It's got a really nice, almost dynamic range that adds to the timelessness of the record. You can't place the production at any one time.

Jeff Parker: That was the goal. I'm glad to hear you say that. That's what I was trying to do.

Lawrence: I'm curious about your role as a solo performer and your role as a collaborator. How do you navigate those two creative identities? Do they ever come into conflict?

Jeff Parker: Ever since I started to make my own music, it's been harder for me to collaborate. For a long time, especially when I first started to collaborate and be in bands around when I first moved to Chicago, I had Tortoise, Isotope 217 . . . we had the Chicago Underground Collective—there were a lot of bands. I was doing a lot of collaborative projects. A lot of music journalists would be like, "Well, when are you going to make your own music?" And I was like, "Well, I'm making my own music. I'm in all these bands with my friends. I'm writing music for all of us to play." It's a beautiful thing—we're all sharing this collective experience. But there's always a compromise. It's always like, well, that part's not right, but so-and-so's doing their thing. It is what it is.

It wasn't until I moved to LA—and honestly, it was because I didn't know anybody out here. If I wanted to make my own music, I had to do it myself because I didn't really have collaborators out here like that. I had my own studio, which I'm in right now—it's just a converted garage space. But for the first time, I had a space where I could work on my own music, and I didn't know anybody. That's how I even came up with my whole solo guitar concept—I had a looping pedal. I'd go to this practice space and practice while my partner worked, and I came up with this solo concept repertoire. Gradually, once I started to make my own music, it put me in a different headspace.

Lawrence: You returned to collaborating, though. You haven't forsaken it.

Jeff Parker: No. Tortoise is active again, and everybody in that band's been doing their own thing. Tortoise was dormant for four or five years. We didn't really do anything. We played our last gig right before lockdown in Japan in February of 2020. Then we didn't do anything else for another five years. During that time, that's when I started making The New Breed and doing my solo records.

It's gotten more difficult for me, honestly. I don't write that much music—it takes me a while. I'm not prolific in the way that some composers are.

Lawrence: Along those lines, though, when you all decide to work together again as Tortoise, how important is it to you that there's something new to contribute to the ongoing story? Because I'd imagine when you go away for a while, you could probably get a paycheck just by coming out and pulling out something you did fifteen, twenty years ago, and people would be really thrilled to see it. How important is it to you to keep building on it as opposed to revisiting it?

Jeff Parker: It's important. Tortoise has been one of those bands that, for better or for worse, doesn't really look backwards. I was always the one—I came and joined Tortoise as a fan. I loved the band before they asked me to be in the band. I'm always like, "Yeah, let's do the thing with the two bass guitars and the vibes and shit." And those dudes will just be like, "No, we already did that." And I'm like, "Oh, come on, man." But we all want to move stuff forward. If you're in a band and people like your band, they come to your show, and they want to hear you play the music that they know. So we have to play the old stuff, but we like to have new stuff too, for sure.

Lawrence: You mentioned the role of mentors earlier. I'm curious about how becoming someone that people look to as a mentor—roles you've played formally or informally with younger musicians—what's that like for you?

Jeff Parker: It's weird to settle into being the older person in the band, to go from being the young dude in the band to being in the middle, and then to being the older person in the band. I've taught formally and a lot at workshops. I was recently on the faculty at CalArts, and I taught at Cal State Northridge.

I think a lot of mentors for me—it's not just giving advice. It's more to give you confidence to be brave enough to present your own ideas. That's the thing that I got most from my mentors: they gave you support and practical advice and guidance, and just somebody to model yourself after, an example of somebody that's trying to navigate whatever they're navigating.

It wasn't until I got older and I met musicians like Josh Johnson and Makaya McCraven who'd been watching my career, seeing me play straight-ahead jazz, DJing, making beats, playing weird pre-improv with Scandinavian dudes, playing on pop records. For me, it's just working, but trying to present it like I'm still an artist, but still work and be creative. It wasn't until I met people who'd been watching that I even knew that I was doing something.

Lawrence: It sounds like, in a lot of ways, because of the curiosity that you exhibit through your work, you show other people possible paths. They don't have to be a straight-ahead jazz cat. They don't have to be a session player. They can do it all.

Jeff Parker: It's hard. It wasn't even anything I was trying to do. I think if I had moved to New York, I wouldn't have found that. I was scared to move to New York because I would see a lot of musicians go there and become regular—they moved to New York and now they're really straight-ahead. Now they're a jazz guy and a New York jazzer. I didn't really want to do that, but I thought that was what I was supposed to do, even though I didn't really know.

I came to Chicago, and I met the musicians from the AACM, and I met the indie rockers, and I was really just trying to work. I had to make a living, and I just wouldn't turn down any gigs. The next thing you know, I was doing a lot of different stuff.

Lawrence: Was there somebody you were looking at and saying, "That's a career I wouldn't mind having," or "That's a path I wouldn't mind emulating?"

Jeff Parker: I had musicians who I looked up to—I think about Herbie Hancock or Bobby Hutcherson, and those guys. If you look at where they started and where they ended up, especially somebody like Herbie, Patrice Rushen, and Bennie Maupin—musicians like that were who I always aspired to. They could do anything. You think of Bennie Maupin—he made that record The Jewel and the Lotus, which is this beautiful minimalist kind of—I don't know what you'd call that music, new music. But then most people know him from playing with Herbie Hancock, but then he's a jazz journeyman playing with everybody in New York in the sixties.

I always modeled myself after musicians like that who just didn't seem like you could put them in a box. But then also great musicians who had their own voice. I remember when I was in high school, they had one of those big festivals like Farm Aid or Live Aid. Santana was playing at Live Aid, and Pat Metheny was playing with him, and I was like, "Whoa, that's like—" He was just doing his thing. He didn't put on a different hat. He had a really strong, singular voice on his instrument, and the music would change around him, but his voice stayed the same. Miles is really the most perfect example of that.

Lawrence: I gather from hearing you talk about The New Breed, it really opened up another path or another lane or another branch of your musical tree. It was the beginning of something new for you. So a decade or so later, where are you on that path? What are you still trying to figure out through music?

Jeff Parker: I'm still trying to figure that out. I know that I want to make The New Breed bigger—not bigger in terms of just bigger, like a bigger or more expansive work, maybe a bigger ensemble, more orchestration, somehow. I think The New Breed really helped me to discover that I really like to make records. I like to work in the studio. I don't like to go on tour so much anymore, so I'm trying to figure out how to really expand on that as a composer, arranger. I'm trying to work at it. I'm trying to find the time to do it.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmChaz Underriner

The TonearmChaz Underriner

Comments