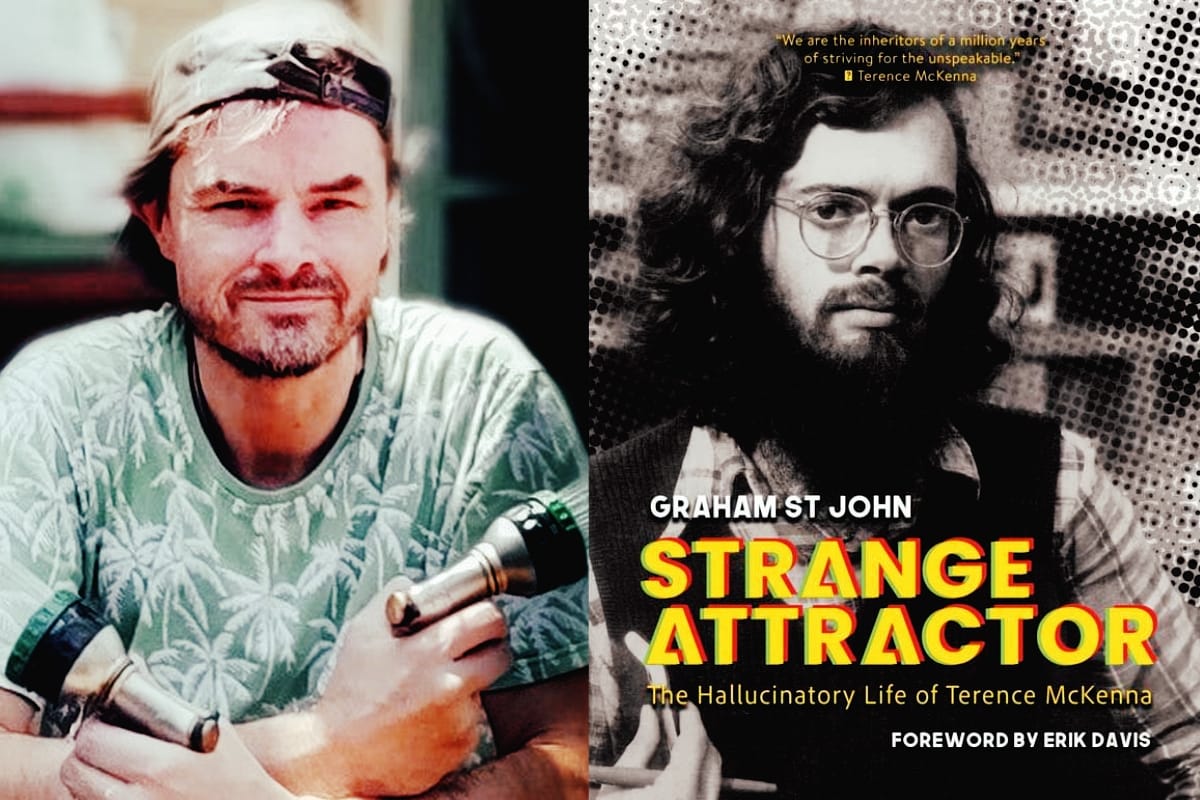

Graham St. John spent a decade assembling the scattered fragments of Terence McKenna's life. The anthropologist and cultural historian tracked down over eighty people, excavated letters that survived fires, and sifted through 500 hours of recorded talks to produce Strange Attractor: The Hallucinatory Life of Terence McKenna—the first serious biography of the twentieth century's psychedelic renaissance man.

St. John arrived at this subject through his own research into transformational events and electronic dance music cultures. As founding editor of Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture and author of books including Global Tribe: Technology, Spirituality and Psytrance and Mystery School in Hyperspace: A Cultural History of DMT, he had already more than dipped his toes into McKenna's world. St. John was uniquely positioned to understand McKenna as both an intellectual figure and a cultural phenomenon, whose voice is surprisingly ever-present on rave dancefloors.

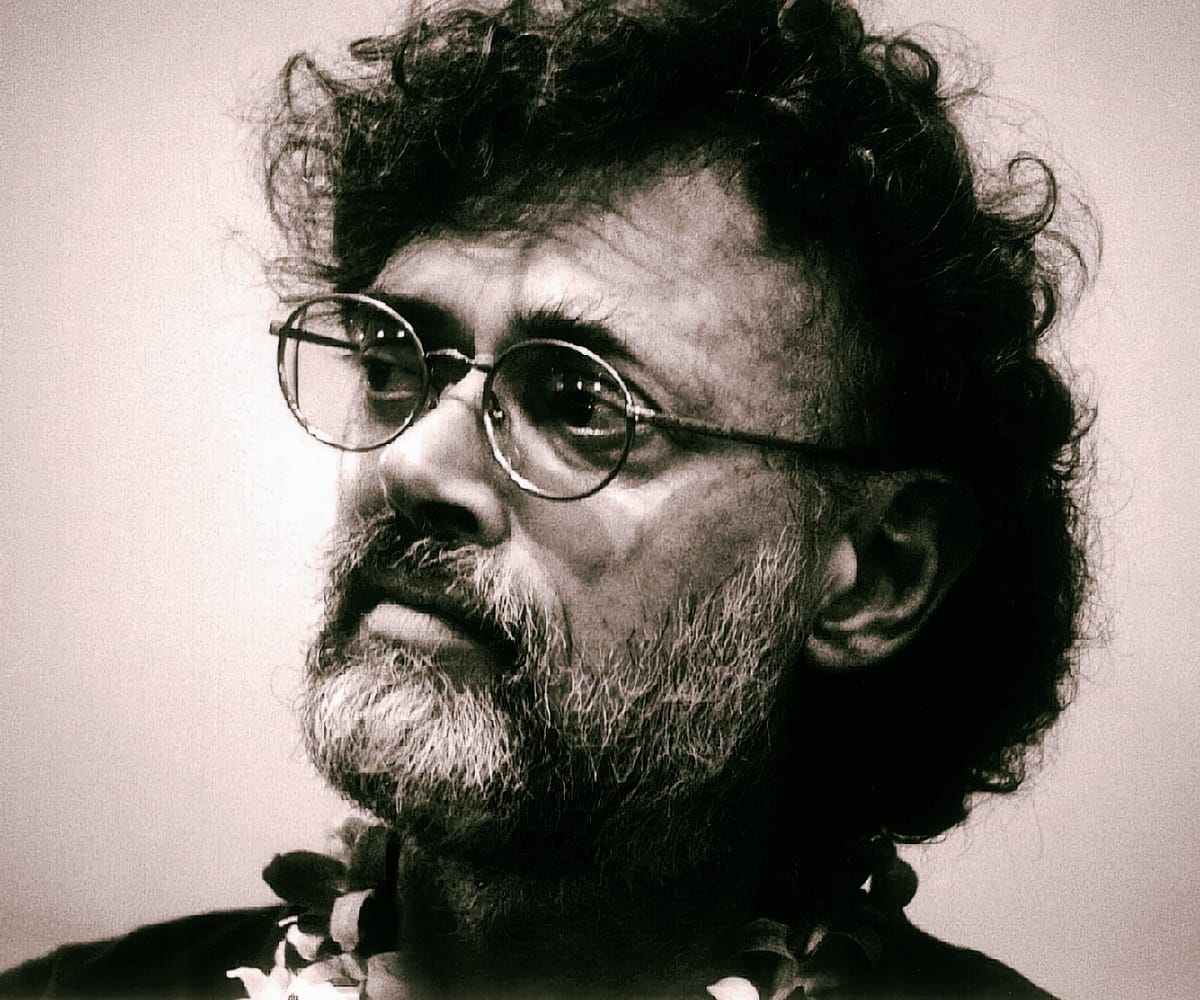

McKenna (1946-2000) perfected what friends called the "Terence McKenna act": a performance of ideas delivered without notes, synthesizing philosophy, science, and psychedelic experience with poetic charm and razor wit. He developed theories on consciousness, time, and evolution that positioned him somewhere between agnostic surrealism and surreal agnosticism. Contemporary psychedelic science regards him as a preposterous anomaly, while the psychedelic underground embraces him as a heroic figurehead. Even his brother Dennis, a respected ethnopharmacologist, acknowledged that Terence "minced facts," though the artistry mattered as much as the accuracy.

Strange Attractor attempts neither exaltation nor condemnation. Drawing on original documents, rare photographs, and previously untold stories, St John chronicles McKenna's role as rogue scholar, stand-up philosopher, and what he calls an "accidental psychopomp"—someone who initiated untold others into mystery while resisting any claim to special spiritual status. "I wouldn't trust any organization that would accept me as a member," McKenna once said, possibly paraphrasing Groucho Marx, capturing his aversion to tribes even as he became a figurehead for multiple communities.

Lawrence Peryer recently hosted Graham St. John on The Tonearm Podcast for a heady discussion about McKenna and St. John's exhaustive account of the controversial figure's life. The two discussed the challenges of biographical detective work, McKenna's split reception between psychedelic science and underground culture, his entanglements with rave and electronic music scenes, and whether the twenty-first century could produce another figure remotely like him.

You can listen to the entire conversation in the audio player below. The transcript has been edited for flow, length, and clarity.

Lawrence Peryer: The subtitle for the book is The Hallucinatory Life of Terence McKenna—"hallucinatory" rather than "visionary" or "psychedelic" or any other variety of words one might choose. Tell me about that specific word choice. What does that capture about his life, and how did it shape how you had to approach his life?

Graham St. John: I guess I could have gone with "visionary" or "psychedelic." But his memoir True Hallucinations was his life project, certainly through the seventies and eighties. He's been a challenge for any biographer over the twenty-five years since McKenna died. And one reason is that it's difficult to know where McKenna's hallucination ends and the truth begins.

His brother Dennis McKenna, who's still around and a well-known ethnopharmacologist, would often say that his brother was someone who minced facts. In other words, he was a major bullshit artist. And I emphasized the word "artist" because, for a significant part of his life, Terence developed the whole 'Terence McKenna act,' performing for wider and wider audiences. He embellished the content, making it a very unique roadshow. He stepped into no one's shoes, and no one has stepped into his shoes.

Lawrence: One of the things that strikes me about you assembling this work is the detective work. I think about that in the context of the fires and the loss of his archives and material. Yet by the time I got to 1970 in your book, I felt like I had a day-to-day sense of what was happening in McKenna's life. You have such rich detail for someone whose material was lost. It feels a little bit miraculous.

Graham: The whole process seems like a miracle. I was fortunate to meet and interact with over eighty people. Rick Watson, his buddy from high school—the guy who gave him the DMT when he got the machine elves in February 1966—was instrumental. He's no longer with us, unfortunately. The book is dedicated to his memory. Without him, I don't think it would've happened. We're fortunate to have the letters Rick shared with me—about 25 from 1968 onwards. Also, Rick's unpublished short stories, including "Morning Glory," which details their first trip together on morning glory seeds in 1964 in San Francisco.

But I should add that this is not the final word on Terence. His daughter, Klea McKenna, is excavating her archives, retrieving all these boxes. I'm sure others will further excavate the life of a fascinating figure who is still one of the most well-known yet little-known psychedelic intellectuals—a stand-up philosopher of the twentieth century who, despite moving to the next level twenty-five years ago, continues to haunt the present.

Lawrence: You refer to McKenna as a master bullshitter, but also as someone who contributed so much to science, humanism, and the hidden arts. He used facts liberally in the creation of a good rap. That wasn't something he acquired later in life. The first quarter or so of your book really establishes early on that that was one of his true gifts—this oratory and this ability. People didn't even care if he was being fabulous; in fact, it was probably part of the draw for his raps. But how do we take his contribution seriously, knowing there is this trickster element to what's going on with him?

Graham: I suppose that he was so consistent and persistent—paradox was such a guiding principle for the way he thought. He's a guy who, in the same sentence, would promote saving the planet and leaving the planet at the same time. But he would do that in such a way that was entertaining and mesmerizing. He was the stand-up philosopher, stand-up eschatologist. There are no parallels with that.

From the mid-eighties onwards, and back as far as 1972, we have recordings of his voice—over 500 hours of content. You can trace the course of his ideas over from week to week, month to month, over a couple of decades. He's a guy who was just riding this intellectual rollercoaster because every one of those raps is remarkably unique. He prided himself on not repeating himself. He also had no props or notes. He had this remarkable capacity to retrieve and synthesize information. He was hilarious. So people would come away from those raps feeling entertained and exposed to insights. There's this levity and gravity in a balancing act in his rap that's so unique.

Lawrence: I know there are different styles of orators, but those are very similar attributes or impressions I get from Robert Anton Wilson—this combination of mind-blowing, heavy content wrapped in such a charismatic, funny, and accessible delivery mechanism.

Graham: And with the good fortune of having communicated with a lot of his friends from high school and UC Berkeley, where he was between 1965 and 1975, we're privileged to get insight into the development of his ideas. A lot of people showed interest in the chapter about the Telegraph House on Telegraph Avenue, where he would hold court. But going back to school in Paonia, Colorado, he developed this capacity to entertain folks, like a jester, squeezing expletives into fast-running narratives just to entertain people who might otherwise beat him up on his way home from school.

Lawrence: I was speaking with someone who was a few years ahead of him at Berkeley and wasn't familiar with who he was. I was trying to explain in a sentence or two who he was, and I said, "I guess you could think about him as like the Timothy Leary of plant medicine." I knew how much disservice there was in that, but I couldn't think of another way. And hearing what you said there, I wonder if there is some truth in that analogy in that mixture of science and philosophy, and, just to say it plainly, recreation and finding the joy and the mystery in these different medicines.

Graham: We're talking about someone who wore so many hats and masks and personas, often simultaneously—a freak, an exile, an outlaw, an anarchist, a heretic, an agnostic, a prophet, a bard, a surrealist.

I suppose I've conducted myself somewhere between being Sherlock Holmes and Captain Willard chasing Kurtz up the river. But ultimately, I'm no assassin, and this is a largely sympathetic work. It tends to be balanced, nuanced. There may be others who arrive with less sympathetic agendas and mine my work to fit them. But no, this is not a character assassination. It's an attempt to understand the fullness of this figure, who's one of the most beloved yet still enigmatic.

At the same time, McKenna is a heroic figure in the psychedelic underground, from his life through the present, essentially a cult figure. But he's also something of a persona non grata in the world of psychedelic science, including contemporary psychedelic science, where he's regarded as a preposterous anomaly. I mean, these divergent viewpoints really drive my interest in him.

Lawrence: You introduced this idea earlier, and it's something I'd like to probe a little bit with you, which is this split reception or esteem or how he's viewed between the psychedelic science world and the underground culture world. There seems to be a pretty significant difference, if not a gap, between how those two scenes dig on him. I'm curious if you could talk a little bit about that.

Graham: I don't know that there's any resolution. It's undoubtedly a division that fascinates me. I think much more could be said about it than I've written in the book. I'm working on another project that attempts to go deeper into his iconoclastic metaphysics. I suppose the approach made evident by his brother, who is a scientist, and their differences are evident. I mean, one of the pivotal moments was the Experiment at La Chorrera, where the brothers ventured into the Amazon in 1971 in search of an organic form of DMT. They ended up not finding so much DMT. They found mushrooms instead.

Lawrence: ...all the mushrooms. (laughter)

Graham: Yeah. Fields of bounty, a supply of Psilocybe cubensis. The page turned, and a whole new development happened. I attempt to convey how significant that moment was. This was La Chorrera, a mission in Colombia, which essentially became Terence's sacred temenos. He never came down from that trip.

Lawrence: It's interesting. I think we struggle because, unless we've done some work to counteract the conditioning, we have this point of view about the divide between science and hidden wisdom. We haven't, at a societal level, remembered what we once knew about the connections among these different ways of making sense of reality. And I think he presents a specific challenge to that because he is smack dab in the middle of that vortex of the meeting of the mystical and the practical. That was the work he was doing, right? Trying to maintain some semblance of scientific language while venturing into this incredibly ambiguous. That seems to me to be the central challenge of making sense with McKenna—like, how much rope are you willing to give him when it comes to his theories?

Graham: I suppose among the many dozens of people whose stories have been layered into the book, the chief admonition has been that it better not suck. There's been a lot of pressure to produce a serious biography of Terence. And I think that is largely because he spoke to so many people directly throughout his life and subsequently. I think Terence is a phenomenon, and, as with all phenomena, there are a multitude of opinions and investments. So rather than claiming I could be some sort of authority on McKenna, the best I can do is provide people with material that will augment and enhance their own existing views.

Lawrence: You seem ideally suited, if you don't mind me saying, to have been the one to take this pass at this book at this time. I say that because of your work in these music- and culture-based tribal communities around dance music, and in this liminal world where music, technology, and consciousness are all wrapped together. Do you have an understanding of what accounts for your attraction to these realms?

Graham: You mentioned the word "liminal" there. I suppose that's probably the key word. I never met Terence. Still, I guess that I first 'met' him when his voice was whispering into my ears in various states of discombobulation on dance floors in Australia and around the world. We're talking about a figure that electronic musicians, especially in psychedelic electronica, have sampled extensively. In fact, I think the case can be made that we're talking about the most sampled individual in the history of electronic music.

So he was already a disembodied voice from the early nineties during his own life. He courted the rave and acid house scene at the turn of the nineties. He quite extraordinarily became a figurehead of that scene, kind of like a raving frontman, and ended up being sampled by a UK act called The Shamen on a track called "Re:Evolution," which reached number 18 on the UK singles chart in 1993—a completely extraordinary circumstance that no one would've predicted. And I do attempt to convey his role in the emergence of Goa trance and psytrance, which was completely unintentional in terms of the DMT that found its way from him into the hands of Shpongle, which formed essentially as an elegy for McKenna around the time that he left the building.

In 2000, we're talking about a figure who is like the 'net era exemplar of a figure who's in a constant state of arrival whilst always departing—in that when he did depart in 2000, just in the wake of the emergence of the internet and virtual reality, he'd arrived and has continued to arrive over the last twenty-five years, such that there are more links than a sausage factory.

Lawrence: After reading the book and now sitting here talking with you, his interactions with the rave world were more multifaceted than I realized, because I wasn't previously aware of the extent of his role as a supplier and thus being one form of inspiration for the community, the scene, and individuals. I think I always just wrote it off as, "Oh, it's a trippy voice saying trippy things that people want to put in trippy music." And that's one level that it could be, but that's not all. How does McKenna fit into the larger story of that culture as it moved from the eighties into the nineties?

Graham: Certainly, a case can be made for McKenna's role as a psychopomp. Having been exposed to the Eleusinian mysteries and notably from that February 1966 moment onwards, when he first smoked DMT—something he was not prepared for—he had a conversion-type experience that he spent the rest of his life trying to understand. Through sharing DMT, firstly with his friends and then the wider community, and then the global community, he was on this mission, this quest to find others who replicated his own experiences. I'm not sure he ever actually did. But the case can be made for his role as a mysteries initiate who, throughout his life and in his afterlife, initiated untold others into the mystery.

Given we're talking about a figure who ten years after he departed was just being massively sampled within electronic music subcultures and event cultures, he served the role as a kind of meta-trip-sitter for people in transported states of consciousness at events or in the comfort of their own home—serving as this psychopomp not in any official sense, almost like an accidental psychopomp, like an accidental cult system. I mean, he was a guy who rejected any sense that he was special or a guru or had any special spiritual facets and features to him, which also makes him, to me, all the more fascinating. That resistance to being, the ambivalence that he had towards leadership, only attracted people all the more.

Lawrence: Very similar to somebody like Garcia or other people who were clearly de facto heads of their scenes but would not ever admit to it. What's interesting, too, is the intelligence, or perceived intelligence, inside, behind, or accessed through the DMT, whether it's the elves or the effects people claim it would have on things like electrical systems. I was just reading a book about the Grateful Dead's Wall of Sound, and there was a section where they talked about how they banned DMT from anywhere near their sound system because whenever somebody smoked DMT near it, something went wrong. It became a superstition for them.

Graham: That's the first I've heard of that particular case. But I did recently read Dennis McNally's biography of the Grateful Dead, and I was fascinated to learn that Terence had an impact on them in the seventies. The brothers' book, The Invisible Landscape, was distributed at a band meeting, probably within a year or two of its 1975 release. Jerry had this well-known take on their book and their ideas. And what's also fascinating is that around that time, mushrooms were becoming prevalent among users in the Dead community at shows. The same people, like Jerry, who were promoting Terence's ideas, probably didn't know that the brothers also produced their underground cultivation guide, Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide, which sold 200,000 copies. The same guys were responsible for this sudden flourishing of domestic cultivation that enabled people to take control of the means of perception.

Lawrence: And he seems to be such a fascinating manifestation of this story that Erik Davis and others have talked about over the years of this profound connection—to me, it's such a California story. He's such a Californian. This occult insight and awareness matched with the bleeding edge of technology. And there were these visionaries who, it seemed, had to straddle both of those worlds to make some of these fantastical things that we take for granted every day appear. He seems to be more on the theoretical end of that spectrum as a seer.

Graham: There has been more scholarly attention in recent times. You mentioned Erik Davis. His book High Weirdness is one of the first genuine efforts to excavate and triangulate McKenna's contributions. I think this must be said about the uniqueness of McKenna's role as a psychedelic occultist and his position in the history of the American occult, which is interesting because he disparaged the occult, notably theosophy and practitioners of magic(k) like Crowley. He thought they were all charlatans. But ultimately, their problem for him was that they weren't stoned enough. So he was a guy who disparaged the occult but at the same time had a deep fascination with Hermeticism and alchemy, collected Hermetic works, and was really into the I Ching. But his vision is quite dogmatic about any effort to enter hyperspace that wasn't metabolically orchestrated by one's interfacing with tryptamines—notably DMT and psilocybin. He was persistent about that and hilarious about that, too. We can't forget we're talking about the stand-up philosopher, and that's a pretty unique role in the history of both stand-up and philosophy.

Lawrence: How would you describe and potentially assess his attitudes and relationship with traditional shamanic practices and Indigenous traditions?

Graham: He had an ambivalent relationship with Indigenous authorities, which is really an echo of his relationship with authorities in general. He had his differences with his wife and muse of seventeen years, Kat Harrison, and very different relationships to Indigenous knowledge, especially over ethnobotany. But I think he saved his best vitriol for academic authorities. He just repudiated academic careerism and was averse to belonging to any club or tribe. His response to authorities, whether religious, scientific, or cultural, was to reject all authority. And it's a source of fascination for me because he has become and remains an authority of sorts for many folks, especially within the psychedelic community. He became a figurehead of cognitive libertarianism.

Lawrence: Given the unique place you sit in your interests and your work, what do you make of the archaic revival concept? How does that resonate for you, and how do you see the lowercase-T truth behind that concept?

Graham: Of course, he claimed that he got all of his best ideas from the mushroom, from his interfacing with the mushroom. And he always emphasized the heroic dose of mushrooms—five dry grams in silent darkness—which was a ritual he pursued for fifteen, twenty years. One of those ideas was the so-called Stoned Ape theory—that our hominid ancestors' interfacing with hallucinogenic mushrooms was the missing link in human evolution. The idea of the archaic revival was that our return to using mushrooms would be, or would become, the main thrust of the revival. Yet there are so many aspects of this revival that fascinated him—the surrealists, Alfred Jarry, and many developments within the twentieth century. And his temporary immersion in the rave scene evoked his understanding that rave culture represented this revival.

Lawrence: You mentioned earlier that you hope, and sort of suspect, this is the beginning of scholarship and insight into McKenna, his life, and his work. I'm wondering what questions you hope to pursue, or that others might pursue, about him?

Graham: Well, I think there are so many, and I'm excited by the prospect of people completely throwing spanners in the works as well. Once Klea McKenna's mission is fulfilled and she makes these materials available institutionally, there will be a kind of Terence McKenna Research Center. At the moment, there is an archive at Purdue University in the Betsy Gordon Psychoactive Substances collection, where Dennis McKenna donated content in 2013. I visited in 2019, and it's currently the best resource for Terence's material. I'm really fascinated by his place in the history of Western esotericism—whether that's agnostic surrealism or surreal agnosticism. His surrealist and gnostic bent, and their combination, are fascinating.

Lawrence: Some people seem so of their time to the point where it doesn't appear they could have either lived in any other time or that their life could be duplicated in our current time. And I wonder, does Terence strike you as one of those people? There's no Terence McKenna of the twenty-first century, I take it?

Graham: No, not that I'm aware of. I don't think we'll ever—certainly not in our lifetime—see a replication, and possibly never. I mean, even though I've finished this biography that I've spent ten years working on, I haven't heard all of his recorded content, and I know that there's so much material out there that hasn't even been digitized. And so I do hope that this work encourages folks who have stuff in their archives to go about digitizing it. I'm quite sure that, as the first serious biography of Terence, it will provoke others to join the conversation and to excavate their own archives.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments