Why Frets? by composer, intermedia artist, and performer Marko Ciciliani is a transmedia work in multiple parts created between 2021 and 2023. There are two performance works: Why Frets? - Downtown 1983 for live electronics and three prerecorded guitarists on video, and Why Frets? - Requiem for the Electric Guitar, a performance-lecture originally for speaking electric guitarist but recorded as a lecture by Ciciliani with integrated audio, video, and slides. There is a mixed-media installation of four intertwined electric guitars, Why Frets -- Tombstone, and a net-art experience, Why Frets? -- Necromancy. Lastly, there is a multimedia book, Why Frets? 2083, with a USB loaded with video documentation of these works and fictional found objects and articles about the works in the series.

Marko Ciciliani is an artist based in Graz, Austria, where he is Professor of Computer Music Composition and Sound Design at the Institute for Electronic Music and Acoustics (IEM) of the University of Music and Performing Arts Graz. His work has been performed in over forty-five countries and documented in numerous CDs, multimedia books, academic articles, and lectures. Ciciliani is currently working on a new transmedia work called BAROGUE.

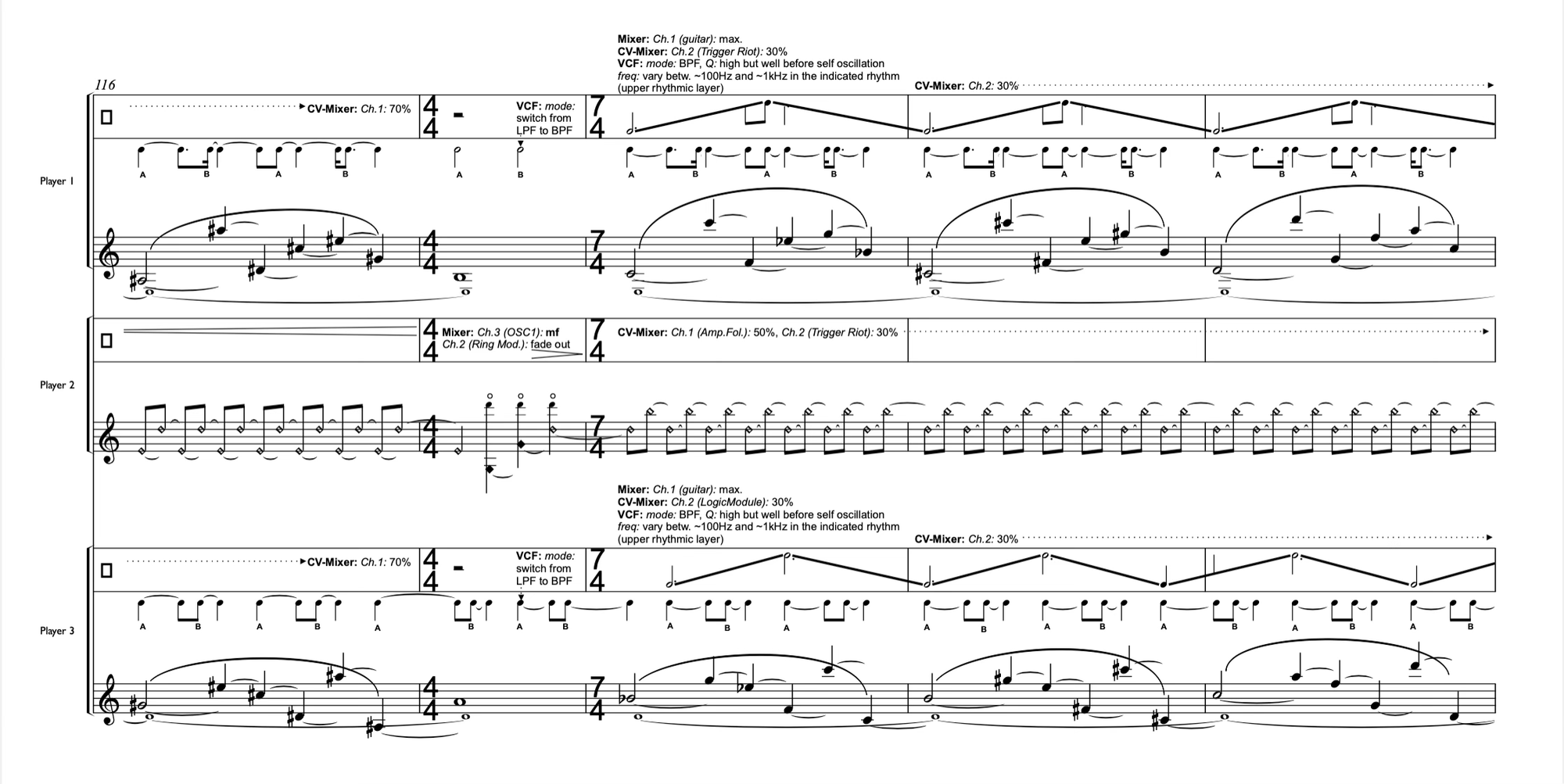

Why Frets? -- Downtown 1983 (preview video here) is a compelling collection of images and sound over twenty-six minutes—videos of eighties downtown musicians, Fender Stratocasters, the precise performance of electric guitar harmonics in just intonation, and Ciciliani at his racks of modular synthesizers remixing, glitching, and recomposing the three prerecorded electric guitarists. There are multiple cycles of playback of the microtonal guitar composition with different live-electronic approaches and video art for each iteration.

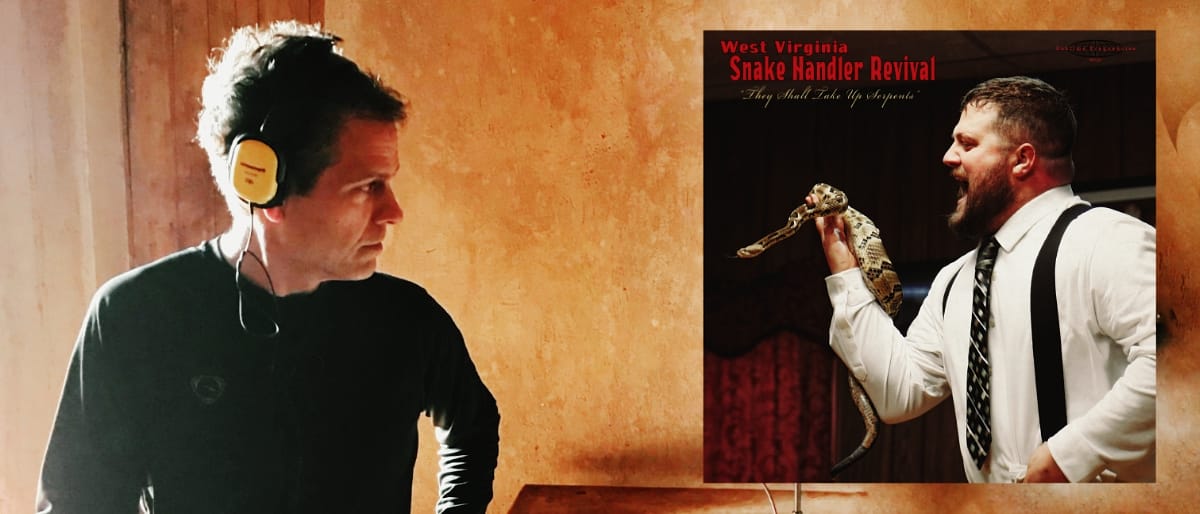

There are layers of meanings and contexts built upon and affecting each other—European new music presented as an imaginary retelling of a lost artifact for a foreign past that is more present than ever. Why obscure the origins of the art object? Like magical realist and speculative fiction writers, Ciciliani constructs a complex context for his expression, a rewriting and remixing of reality into a surreality. A bit-crushed mythology results, remixing the self and reevaluating the electric guitar as an aesthetic object. A live-glitched history of a glorious artifact, folding upon itself.

I found myself asking, "Does the work need the contextual remixing?" I find the composition for three electric guitars interesting on its own, without explanation. My conversation with Marko Ciciliani in his studio in Graz about Why Frets?, intermedia art, and his inspiration from his time in the New York downtown music scene in the nineties examines these questions.

Chaz Underriner: I'd like to start by talking about your evolution from writing notated concert music to doing multimedia and game-based work and having a more expansive view of your work in general. Can you talk about that change and transition for you?

Marko Ciciliani: It's something that went very slowly, and I see it as a sort of gradual shift of focus. I don't even see it so much like a transition from A to B, but more as a mixing of things. Within this mix, gravity sort of shifted into another place.

I've been working with electronics from very early on, when I started composing instrumental music. Then, about twenty-five years ago, I started experimenting with visuals. The shift that happened is that basically, technology became more and more interesting to me as a sort of artistic reflection. In that context, I also became more interested in working with smaller settings.

When I started out as an instrumental composer, I had this dream of writing for big ensembles—the usual stuff. This somehow became less and less attractive for me because when working with technology and performers, I found it beneficial to work in small settings. I find it very interesting to construct special relationships between the technology and the musicians. This is more transparent when you have small settings rather than larger settings. With a larger ensemble, technology easily becomes a sort of add-on, but when you're working solos or duos, you can balance the situation and work in more delicate ways.

This is where I gradually evolved to—I found it more interesting to work with smaller settings or to compose pieces for myself, like Why Frets? In this whole context, the visual aspect became more interesting for me. My PhD thesis was about the relationship between sound and light, which I started in 2007 at Brunel University of the Arts in England. It was only after I finished my PhD in 2010 that I dared to touch video. I wanted to figure things out first on the basis of sound and light, which resulted in compositions where I used lighting design as an additional musical voice, you could say.

I am now combining forms of storytelling, which you see very prominently in Why Frets? When I'm using video, I'm still interested in designing visuals in such a way that they have a very strong musical quality. But I'm more and more interested in what visuals can contribute as a space of associations and of additional content, and to establish a sort of atmosphere. For a while, I called myself an audiovisual artist, and nowadays I call myself an intermedia artist, which is to say that I now include other media than just sound and visuals. My work goes into the usages of text but also into designing particular forms of performance.

Chaz: I'm glad you brought up the use of text and storytelling, because those are some of the things I have questions about. This also forms an evolution of multimedia work for me, to make the text yourself. The use of text in itself is not a revolutionary idea, of course, but to tell stories and to build mythology in the way you're doing it is really interesting. One thing that stuck out to me is the material you wrote for the three guitars in Why Frets? -- Downtown 1983.

In an essay in the book accompanying the work—"Showing Promise: Anthony Finto, three electric guitars and the future of tuning" by Guy Kahn—the article mentions the use of harmonics, just intonation, and the aesthetics of Morton Feldman for the work. But then, instead of presenting it as an instrumental piece, you shoot it as a video and then use the video within a larger work in different ways, either processing it with electronics or using it as interludes within a lecture. My question is: why? You have this piece, which to me sounds like a fully composed work that could exist as a standalone instrumental piece or video piece, and then you bring it into this other context with storytelling and other forms of presentation.

Marko: When I composed this piece, I started with this trio, and I didn't yet know where I was going with it. I just knew I was composing a piece for three guitars, and there's probably going to be some electronics. I composed this four- or five-minute piece very quickly, in a day or two. I really liked it, I have to say.

But it just didn't work with the whole concept of the piece because I already had the idea for Why Frets? sketched out. It was clear that this whole work was going to be reconstructing the electric guitar based on a fake history from the perspective of 2083. Therefore, I thought, "Wait a minute, I'm composing a piece in a fictitious time when nobody plays guitar anymore. So what am I doing here?" I can't put three musicians onstage and let them play guitars because this is just not happening in 2083, according to my story.

I brought myself to a sort of dead-end street because I realized, "Okay, this is a nice piece of music. I really like it, but I just can't do it. It just doesn't fit into this project as a whole." I started wondering, how can I find a way out of this? Eventually, I had this idea to present it as documentation of a concert that occurred in 1983. That's how that part of the story evolved. It also has some autobiographical aspects because I started in New York in the nineties, studying at the Manhattan School of Music from 1993 to 1994. I went to New York because I was a big fan of Morton Feldman and John Cage, and they were a strong influence on my writing. I also placed that concert at Roulette, which is a little autobiographical because I used to work at Roulette when I was a student in New York. There are many emotional attachments to the story, but at the same time, I had to subvert the whole thing and turn it into this sort of historical document.

Chaz: What was the scene like downtown in the nineties, when you were there?

Marko: I don't know how it is today, but it seems to be that today it's much more polished. Back then, it still had this sort of rough downtown edge. In New York, everyone tells you all the time, "You should have been here ten years ago." In the nineties, they told me, "Oh yeah, you should've been here in the eighties." If you had been there in the eighties, they would have told you, "Oh yeah, you should've been here in the seventies." They always gave me the feeling of being too late. But I think if you compare it to today, it really had an underground character.

At the same time, Roulette was an established place, but you could still feel the resonance of—still fully alive—the improv scene around John Zorn and Naked City. Then you also sometimes had the sort of post-La Monte Young people who came there with just intonation. This whole New York history, even though these things were already a part of the past, was still resonating very strongly, which they probably don't do in the same way today.

I'm so grateful to this friend who told me back then, basically the first day I moved to New York, "Yeah, you should go check out downtown, and the best thing is to get a job there." I thought, "Okay, let's give it a try." I went to Roulette and just asked, not for a job, but, "Do you need a volunteer to help out?" That was it. I was selling tickets, and in return, I was able to listen to the concerts for free. That was totally amazing because that way I listened to several concerts a week at Roulette, and I spent my days at the Manhattan School. I had a big dose of both of these cultural scenes. The uptown composer thing and the downtown improv thing. It was brilliant.

Chaz: Now getting into Why Frets? itself. Talk to me about your concept of 2083. Why this mythology? We were talking about downtown New York in 1983, but it's a much bigger project in scope than just that one point in time.

Marko: Yes, the main story is, of course, told in the whole lecture (excerpt here). It's all about rewriting the history of the electric guitar and attributing its invention to Siglinde Stern. To speak about the meta idea, what I want to achieve is speculative storytelling. You're making something up in order to completely change the perspective, and suddenly, you see something that you have always been surrounded with in a different light. You might establish a different relationship to this phenomenon than you had so far. This is, in a way, my goal with the electric guitar. The reason why I did this is that I feel sentimental about the electric guitar. I really like it as an instrument a lot, and I find it such a versatile instrument.

I don't play the guitar myself, I have to say. That's something I'm often asked, but I'm really incapable of playing the guitar. I have many guitars, ironically, but I don't play them. It's a very loaded instrument. It has this kind of masculinity thing, which is very much in the foreground of rock music. This gender aspect was something that I definitely felt was interesting to tackle by rewriting the history. That's why I chose to attribute it to a female inventor. That's also why I constructed the story in such a way that the instrument became so oversaturated with testosterone that it just died out.

Chaz: That's really lovely. For you, it's a critique and a joke about the electric guitar—that it's so ridiculously phallocentric that it crushes itself under its own weight, and it's a perversion of its invention by this distinguished woman. As a guitar player, I think the critique is really warranted. In the lecture, how much do you want the audience to be aware of the fiction? Because I had never seen the schematic you have with the Rickenbacker pickup, I wondered, "Is that made up or real?" You're playing with me, right? How much do you care that I know about the source material?

Marko: I give away that it's a fake story in the second or third sentence, but nobody ever notices. I think I say something like, "One hundred fifty years ago, the Rickenbacker blah, blah, blah was invented." If you make your calculation, you realize that means that we are in the year 2083, and obviously, we're not in the year 2083. I'm just pointing this out because I don’t try to hide the fact that this is a fake story. The sentence just goes by quickly, and nobody makes the calculation. Very often, people tell me that they don't realize until the last five minutes that everything I'm telling them is made up.

That's okay with me, but it's not my intention to make people feel stupid or to betray them or whatever. I'm trying to create a story that is as close to the truth as it could be. But then, of course, the key elements are made up. But the schematic is an original. Yes, it's true that it's the Rickenbacker, and many of the historical figures I'm referring to are also authentic. I would have to go through this in detail to say this with certainty, but if I'm not mistaken, Siglinde Stern and the Sisters of the Harmonic Constellation are my invention, and everything else is true.

Chaz: Oh wow, so there are more touches of reality to it than I thought. I'm coming at it as an educated audience member and a professional guitarist. I'm certainly not an expert on the history of the guitar, and even though I've studied some schematics, I hadn't seen that one before, so I didn't know if it was a true historical document or not.

I also didn't do the math in the lecture of oh, one hundred fifty years ago, etc. But I had the book, which I think makes it more explicit. Tell me about the book: why did you decide to make it? I'm curious about the essays about the work by, for example, Fiona McDeer and Guy Kahn. Fiona doesn't sound like she exists to me. But did you write the text? Or are they commissioned by other writers?

Marko: I do credit the writer: the author is Nicolas Trépanier. He’s a professor at the University of Mississippi, a historian, and a friend. He also helped me write the lecture. But all the content is by me. I gave him the complete story and asked him if he could improve it and make it sound more like a real lecture by a historian. First of all, there is this review of the concert...

Chaz: Which is quite funny to me.

Marko: Which you probably figured out is a reference to Kyle Gann's Village Voice reviews. I copied the original Village Voice layouts from the eighties. Again, I gave the whole story to Nicolas with some reviews by Kyle Gann and asked him whether he could write something in this style. Then we did the same thing with the article by Fiona McDeer. He's basically commenting on the lecture and on the piece. That's what the whole text is based on, particularly on the lecture.

Chaz: I love the self-critique and the questions about identity with uptown and downtown. This composer, Anthony Finto, is a poser, right? Like he's totally uptown but trying hard to appear with downtown cred to the interviewer.

Marko: But Finto means "fake" in Italian, and Antonio is my middle name, so Antonio Finto it is.

Chaz: That's amazing—I didn't know that. There was another bit I wanted to bring up where the article acknowledges preconditions for disappointment with the work. I love the self-critique in there—can you tell me about that?

Marko: It's a bit of an extension of the self-critique of Downtown 1983, where I'm saying, okay, this is like this Feldman thing. But then I'm also showing that it's this kind of zeitgeist and everybody's copying a little bit of Feldman and a little bit of La Monte Young and making these sort of dreamy just intonation textures. I'm commenting on the downtown scene with these extended techniques, like playing guitars with ashtrays or whatever. In a way, this is a critique of myself when I was young, because I did this kind of music. It didn't really sound like this piece, but when I listen to the pieces I composed back then, I can definitely hear the Feldman influences and the Cage influences from my early twenties in the nineties.

Of course, I thought I was so cool and original. Looking back, I realize I was definitely not, and therefore I think this article is also a bit of a self-critique of how I saw myself in the nineties. I wasn't quite as bad as this guy in the interview, but...

Chaz: Are those pieces still in your catalog?

Marko: Yeah, actually, they are. I don't really filter my catalog.

Chaz: A lot of people do. I think every composer should be required to write fictional program notes that critique the work that they're doing because I think it takes a level of self-awareness that we're talking about, and the humility and good humor to acknowledge it and put it in context, which just cracks me up. I thought it was fun. Is the multimedia format of performance, installation, lecture, web art, and book—is that a combination that you're interested in continuing, or is that unique to Why Frets?

Marko: No, it's something I'm actually really interested in and that I refer to as a transmedia composition. It's a sort of series of works that are all looking at the same field of interest from different angles. I'm also currently finishing a new project, BAROGUE, which consists of three parts. One of them is again an installation. Then another part is going to be fifty minutes, a string quartet with electronics and four videos. The third part is going to be a solo performance for an audience of four people, a really intimate setting.

I've been working on this project for two years, since this has been a long project, but I like this way of working: to have a particular field of interest and to make a series of works that are looking at it from different angles. This is important for me also, through different media, something I find really, really interesting. I would say this is my current field of research, and recently I published an article about it, if you're interested.

Chaz: We have a lot in common in terms of our multimedia artwork, although we've gone in very different directions. But doing large-scale, multipart pieces that take years to do—how do you decide the media of your work? I assume you start a project with some ideas, but then how do you choose the overall combination?

Marko: Sometimes it's a really pragmatic thing. The new string quartet was simply because I met the Neo string quartet from Poland. We met at Warsaw Autumn two years ago, and decided we wanted to work together. This was, in a way, the first thing that was decided before the idea for the project was even there.

It took me quite a long time until I knew what I wanted to compose around this quartet. It's a bit embarrassing, but when I make decisions in the process of composing, I afterwards forget what the real reason was. I can't really remember why I decided to make an installation again. The installation is quite different from Why Frets? – Tombstone, because what I had in mind was that I wanted to work with mirror reflections and spot beams. I knew this was the sort of aesthetic I'm interested in. It turned out quite differently from what I had originally in mind.

What is essential for me is this different quality of the media that I use. Since I already had this classical setting of a string quartet, I wanted to have something where the audience has a little more freedom of movement. Therefore, it was clear that an installation would be a good fit. Then this third piece is also something that evolved quite gradually. Right now, I'm actually in the process of just abandoning the original concept. But what was clear from the beginning was that I wanted to work with these intimate settings that I perform maybe ten or twenty times throughout the day, where people can schedule the time slots.

I'm always performing for a very small group of people to have this intimate quality. There's also probably going to be some participative stuff where the audience does things that influence the performance. I'm very interested in this, which in the article I call the "mode of encounter": how do you encounter a particular work, and what sort of affordances does this entail, and how does this contribute to the overall aesthetic experience? Choosing and designing a particular medium has really become a sort of essential part of the composition that I consider just as essential as the music that I composed—to decide, "How do I create the situation in which the audience encounters the work?"

Check out more like this:

The TonearmChaz Underriner

The TonearmChaz Underriner

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

Comments