After fifteen years of intense violin training, Bryan Senti walked away from the instrument and its associated performance anxiety at eighteen. The Colombian-Cuban American composer spent the next two decades building a successful career scoring films and television—including a BAFTA Award for his work on the BBC series Mood—while the violin gathered dust. When the pandemic hit in 2020, Senti, isolated with his family, found himself once again contemplating the violin. What was his actual perspective on the instrument that had defined his youth?

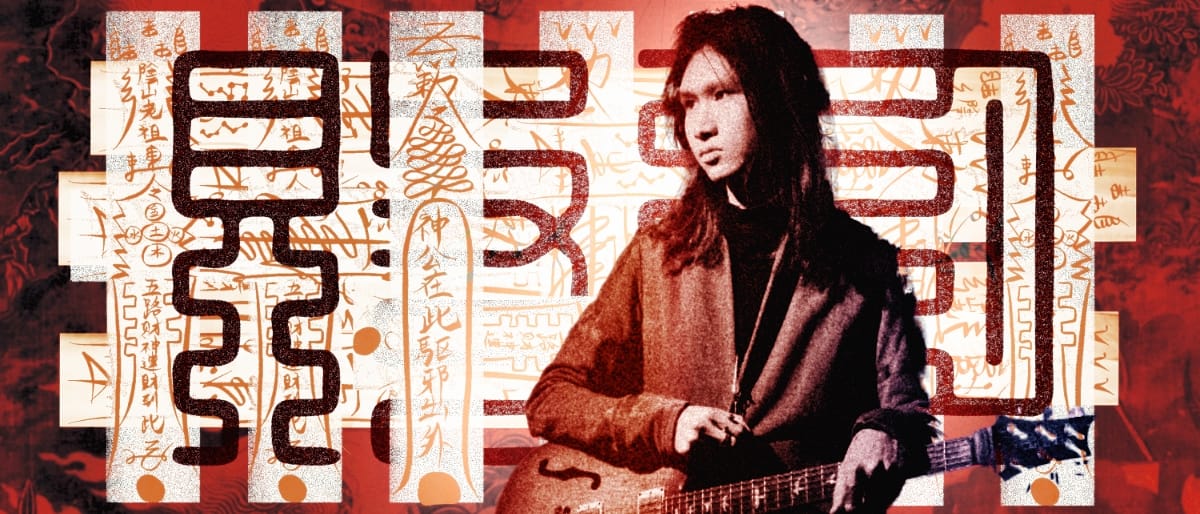

The result was Manu (2022), a solo album released on Naïve Records that began what Senti calls a diptych, two projects examining his family history through string-centered compositions that blend Western classical training with Latin American musical traditions. Manu focused on his Colombian mother's story, evoking the texture and landscape of the Andes. The follow-up, La Marea, shifts focus to his father's experience emigrating from Cuba during the revolution of 1959-1960, inhabiting what Senti describes as "the memory of a homeland that no longer existed."

La Marea (released via The state51 Conspiracy) is an ambitious string orchestra cycle composed specifically for Dolby Atmos. The album features performances from the Czech National Symphony Orchestra, bassist Spencer Zahn, and cellist Noah Hoffeld, with production by Grammy winner Justin Moshkevich and mixing by Francesco Donadello. Manu consists of a series of shorter pieces exploring different articulations and playing techniques, while La Marea expands into larger compositional forms. The central image, Senti explains in the album's press materials, is "that of the proverbial raft, of being alone adrift at sea." The album attempts to capture "that singular combination of grief and faith that brings someone to surrender to inevitable change."

Despite containing no electronics, the album draws heavily on the textures and structures of ambient, techno, and experimental electronic music. The result is what Senti describes as "Guardians of the Galaxy size in terms of tracks"—massive layered string arrangements that converge into oscillating waves of sound. The compositions employ polyrhythmic structures and generative processes to create what the press materials call "emotional waves," reflecting the physical and psychological experience of oceanic displacement.

Lawrence Peryer recently hosted Bryan Senti on The Tonearm Podcast. Senti discussed composing music about his family's displacement, how techno influences his orchestral work, and how this project becomes even more personal as Senti now faces his own migration challenges.

Listen to the entire conversation in the audio player below. The transcript has been edited for length, clarity, and flow.

Lawrence Peryer: I'd like to learn about the importance of telling your family stories now, as heard across two of your projects, Manu and La Marea. What's that about?

Bryan Senti: I feel like these two records are a diptych, and then after that, I'm kind of set free. The impetus started when COVID hit, and the pandemic shut things down; I felt like it was my time to make a record. And it occurred to me that, even though I was a string player my whole life and had done a bunch of projects for other people, I didn't really know what my perspective on the instrument would be.

Furthermore, I struggled with a bunch of things about the instrument and about classical music in general. One of the issues that I had was that I came from a pretty blue-collar Hispanic family—my father was a minister, and my mom was a dental hygienist, both of whom left their countries under duress: my father from the Cuban Revolution, and my mother was an orphan in Colombia. Her father was killed at the beginning of La Violencia, which was their revolution, their civil war. They were people who, while they really enjoyed classical music, for them it was a very elite and fancy thing that they thought their child could go into.

But, you know, we were always surrounded by more humble people. And our families were humble. My father was a minister in the Latin church, in the Hispanic church, and there were dishwashers, people who had just come over.

I felt very privileged that my parents enabled me to have a good education, to go to Manhattan School of Music to study violin, then to Carnegie Mellon, and then to Yale. And I think at a certain moment in time, maybe I even pretended to myself, like, "I could be a part of this aristocratic American class," or something like that.

It occurred to me over the years that that was perhaps a form of self-hate, and that it also didn't honor my family's story. That became a problem for me with classical music in general. And maybe that's why I didn't pursue it in the more traditional sense—I just couldn't completely identify myself with it, as beautiful as it is.

I feel like I'm almost disparaging some of the composers, but that's not the case. I think a lot of people feel comfortable in that space. But with my family story, it didn't. So I felt like with Manu, I had to figure out a way to tackle this issue.

And so my way to tackle it was to look into Latin American folk music, figure out what I could bring to the performance practice of the violin that both honored this story and my classical training, and connect the dots.

I feel like there was a lot of soul-searching in that, particularly with Manu. I started delving into my mother's story, particularly the vibe and ambience afforded through the vista of the Andean Mountains in Colombia. You know, something more salt of the earth. I think when I finally came to La Marea, I wanted to expand out and take some of that style that I had created in Manu and blow it out into something that could create larger compositional forms. Get more experimental, I think, in the composition itself, not just focused on the playing.

I can keep talking about this, but you know, one of the things I did in Manu, in a funny way, was focus on articulations. Each piece—they were much shorter, and they were, in a way, etudes, or short songs if you will, and I was able to focus on different styles. Pieces would focus on pizzicato, for example, or on playing like a guitar, or on different arco articulations. And that felt really good in Manu. And then for this, I went into a much more experimental place.

Lawrence: You've mentioned some of the folk-inspired elements from the Latin American experience. Is the violin an instrument in those traditions, or did you have to find a way in?

Bryan: There are string instruments like the violin. All that stuff was imported through the colonial move from Spain and Europe. So the violin's in there. But it's also adapting to play sounds like a pan flute or the instruments you would find in Latin American culture. What's beautiful about some of the folk music of Latin America, I'm thinking specifically of Ecuador and the Andes, is that you already have this kind of allusion to minimalism, and probably a lot of that is coming from Western African influence as well. You have this beautiful, oddly spiritual minimalism in this music. So these techniques are humble, but they also lend themselves to a kind of magical realism that music suggests.

Lawrence: It's interesting to me because the technique seems to rely less on just being about virtuosity. Something about plugging into a different tradition forces you into a different sort of psychological construct. I don't want to be too heavy-handed, but it just seems very interesting to me.

Bryan: My wife right now is reading The Artist's Way, and she keeps showing me these passages that say that to create a perspective, you have to build this narrative from inside. And I feel like that was my problem, but I feel like that's a lot of people's problems in their own lives, regardless of whether or not they're a musician or an artist. Why do you choose to be a lawyer? Why do you choose to be a doctor? You have to do the requisite introspection to own these choices. Otherwise, should you meet any roadblocks, which you're likely to in life, it just leads to depression because you feel like you don't have agency over things. And I think I relinquished a lot of agency.

And by the way, I think this is a Northeast thing. (laughter) We're pursuing a life for ourselves. We have the goals of maybe having a family, a nice house, and achieving some level of status.

Lawrence: They're like unchallenged assumptions around ambition.

Bryan: There's this book, Consolations [by David Whyte], that has a great poem on ambition and just how ambition is this wonderful fuel that you use in your youth to get you started. It's like a rocket where eventually the fuel evaporates, and then what? Then it can become a curse, because ambition doesn't serve you at some point. You have to move on to serve other things. You've got to serve your family. You've got to serve your partner.

So I say that only because for me, things had been kind of just random choices about career and music. And particularly when you work in advertising and film, you get a lot of directives to compose in different styles. I'm not saying any of that's bad—obviously, you need to make a living. But at some point, if you do want to connect with music and write music for its original purpose, which is self-expression, you're going to need to work on what that narrative is.

And I have to say, and maybe this is the point that you're suggesting, it's helped me in other aspects of my life. It's helped me become a more centered person and know myself much better, so I can interface with my wife and my children. I just started having children at the time I was starting to write Manu, and boy, does it feel good to feel that in ten years' time, when I can actually talk about music with my own children, I could be like, "You know what, this is something that I actually felt. This isn't just the sixty-second commercial that I wrote for Nike, a score where they told me to mix hip-hop with classical. This is something that, in some ways, traces a family story and perhaps will be insightful for you at least, so that you can understand your father better."

Lawrence: Living in Italy while you're contemplating this music about Latin American displacement—does geography come into play at all? Do you get a different perspective, or is that a string I shouldn't be grasping at?

Bryan: What's funny about this record is I finished it right before leaving. And now the record takes on a new significance for me while being here. We came to Italy because we were running out of money after the writer's strike in LA. The city also got very expensive, and we had two kids. My wife had just gotten citizenship a couple of years prior, and we were like, "Well, let's see if we can get other citizenships."

Italy has been amazing in many respects. But we're also learning that it's very difficult to work in Europe. And right now the world is very chaotic. But it made me think about how I never asked my dad about his experience before he passed—I wasn't mature enough to even ask these kinds of questions. But I wonder if he thought he would ever return, and it's obvious to me now that people make moves for their family and because of events, and you're swept up in these events, and you don't really know the implications. I'm pretty sure we're going to return to the States, but it's not a given. Life happens: you can get stuck somewhere, or maybe things take off in a different place.

So I'm in Italy, at the comune, at the municipio, learning Italian, and in a way, also applying for Italian citizenship. I'm an immigrant, granted in a weird first-world way. But it just made me think of my father's story and not have it be so abstract. I don't think the record is abstract in that way, but it was abstracted in the sense that my view of my father's story was an observer's view, the way somebody reads a book or somebody watches a movie. It's a very funny feeling to feel like—it's like the end of The Shining, when Jack Nicholson sees himself. It's like all of a sudden, now I'm in the movie.

Lawrence: Tell me about your interest in techno.

Bryan: I'd say this: I owe a lot of my excitement for techno to my co-producer, Justin Moshkevich. As regards this particular record, he did a very great thing by inviting me to the Movement Festival in Detroit. I saw a Rrose live set, and I was just floored.

A good friend of mine, Paul Corley, who's also a great musician, told me that what's great about techno is that it's all about perspective. It's music reduced to its fundamental elements: a kick drum, a snare, a hat, and these gestures. Every single one of those gestures that you manipulate, even subtle gestures, alludes to sexuality, alludes to a different place, alludes to a different culture, alludes to all these different kinds of styles. But it's not complicated to understand—it's in its construction, it's on the floor, and you repeat and create these gestures.

Anyway, the point is that Rrose's set was so rhythmically elaborate that I fell down a wormhole with this person. Just reading up on how they created, how they worked, and learned that they went to Mills College and knew of people like Pauline Oliveros, Robert Ashley, and all these figures in the far left wing of classical music. It's so far on the left wing that the core classical community doesn't even really know who these people are. An experimental class that you get at the end of your degree may mention these people.

What I loved about Rrose's set was that it's avant-garde techno, but the feelings there are not dissimilar to those in other techno, in the sense that it allows you to feel lost in the rhythmic complexity. Then there would be these moments where things kind of emerge, and all of a sudden the rhythm would come together and things would lock. Those were exhale moments that you would have as a listener, and where you'd be like, "Wow," and you'd get this rush like you were on ketamine. It just felt amazing. I went home right after Movement and worked on "La Marea," the title track of this album. Tehno felt like a connection point and helped me, quite frankly, construct that piece, which for me is the central piece of the album.

After getting it, techno felt really important because techno, again, drawing a connection to folk music—techno is of the people, you know. Techno's not about showing up in a fucking tuxedo at Lincoln Center. It's about an ecclesiastical religious experience you can have at three in the morning in the dark.

Lawrence: Did this impact your conceptualization of tempo or meter? Was that its basic influence?

Bryan: Yeah. Exactly. There's an article on Rrose in Resident Advisor called "Art of Production," which discusses process-oriented music, emerging properties, and these more experimental pieces. It's a generative process, popularized by Philip Glass, Steve Reich, and all that stuff. It could create these audio shapes and audio illusions, like phase music, you know, like Steve Reich. But Rrose came at it from an even more weird avant-garde place. For example, I think there was one piece where they're just rolling on a huge gong for half an hour, that kind of thing. And then all of a sudden, halfway in, you start to hear the other tones and the harmonics develop. But in fairness, in that set that they did, what came together for me was the rhythmic aspect of it, and also the feeling of feeling lost.

Lawrence: You said early on that you've done the family work in your music. So now what?

Bryan: Well, I have to say I feel very inspired. I feel like it's a time for artists to really convey the importance of humanity and human expression. I feel like the world is in a crazy place, so even the smallest gesture is valid. I mean, it's incredibly valid. For somebody to even make music about what's going on stateside in one small area of all the political things happening would be a huge gesture, because there is this push right now to make everything seem like it's all right and okay, and just forget about it. There's this push to disassociate. I understand that, obviously, because we all have to be aware of our mental health. But self-expression is so important so that we know that we're all in this together. So, I am very excited to talk about current situations.

And as I've told other artists who are friends of mine, we're in a beautiful moment, talking about diaspora and different people's cultures. We all come from someplace. There's been this homogenization, and I would say it's true even in Western music. There's this homogenizing of the form into a Top 40 song, you know? And there's a lot of opportunity to look into one's history, to look into one's story, and to try to personalize this experience by talking about where we've come from and how we interact with whatever the zeitgeist is at the moment.

In terms of something I'm doing right now, I'm working with a friend of mine, César Urbina, who's an electronic artist originally from Mexico, on InFiné in Paris, France. We're working on something that's going to be more pop-focused, but also more improvisational, and could perhaps be played in a club or another contemporary setting.

So for me, that's really good because La Marea, certainly even more so than Manu, is serious. You know, I'd put quotation marks there, but it's more serious work just because it's more intense and more introspective. So something that feels ephemeral and more in the moment feels like a good next step, so that I can recalibrate and figure out what I'm going to say next.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments