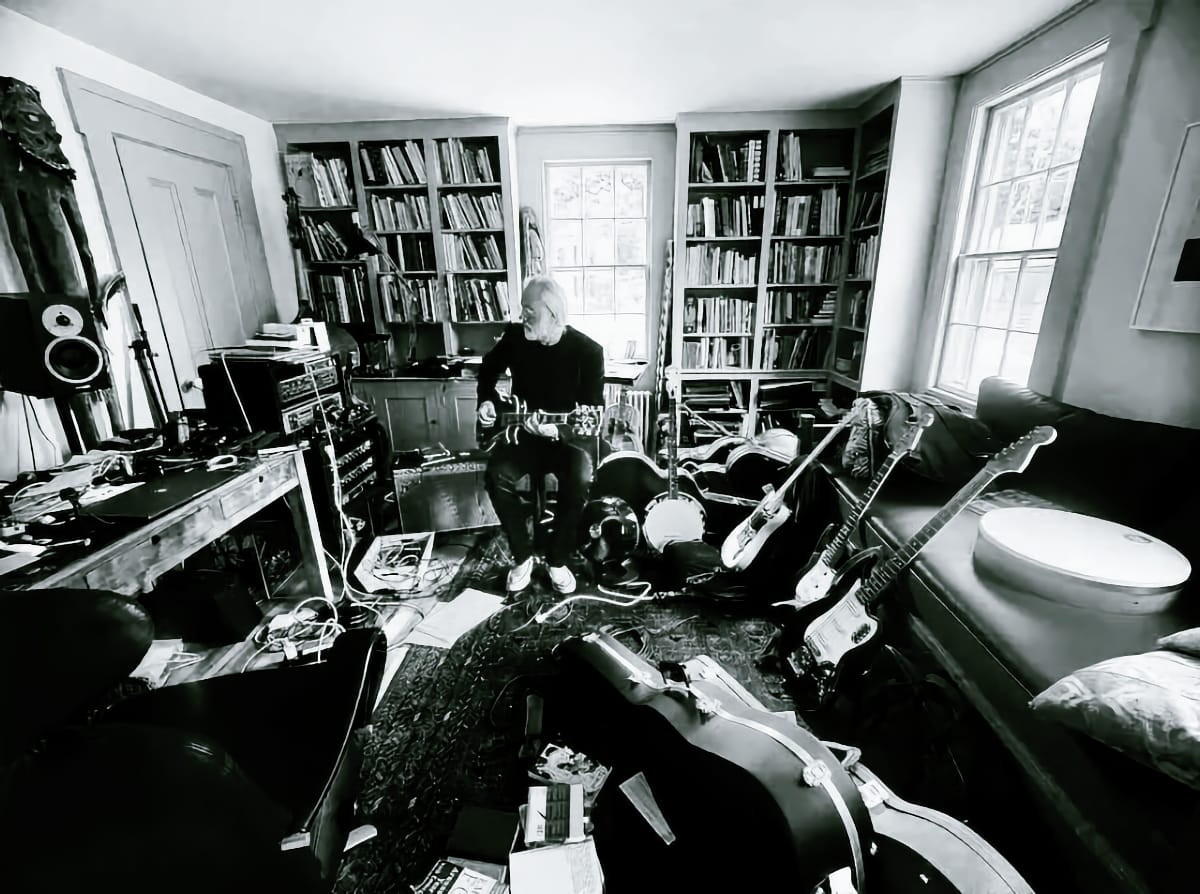

With his new project, Shrunken Elvis, Spencer Cullum wants to honor the pedal steel without reinventing the wheel. After dedicating years to his career as a session musician and solo artist, Cullum's new venture juxtaposes a traditional Nashville pedal steel sound with a soundscape-y, more trance-inducing flavor. The ambient-adjacent trio was born from late-night drives through Europe, touring in a small Volkswagen, listening to krautrock, and writing new songs.

Shrunken Elvis features fellow Nashville musicians Sean Thompson and Rich Ruth, who are longtime collaborators of Cullum's. The music that the trio produces can oftentimes defy definition; one description that came to mind was if the "lo-fi beats to relax and study to" girl were working toward a degree in mushroom horticulture. The record features moments of soundtrack-worthy ambient swells in songs like "That There's A Strategy," which could fit seamlessly into a Planet Earth documentary. "A Faint Rustle" finds a common ground between King Crimson's Frippertronic insanity and the Grateful Dead's "Drums & Space" segments.

A heavy emphasis was placed on organic composition and allowing the instruments themselves to shine. Per a press release for the record, "their goal wasn't to make an instrumental album that highlights individual prowess on pedal steel or guitar—but rather to construct a musical terrain where all elements coexist," without overcrowding a listener's musical palette. Their self-titled debut record was released at the beginning of this month via Western Vinyl.

I spoke with Spencer about the journeys that influenced the record, his experiences relocating from the UK to Tennessee, and how important it was to capture the pedal steel's brilliance within the experimental nature of Shrunken Elvis. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Sam Bradley: When did you start playing pedal steel? Was that sort of the basis for your move to Nashville?

Spencer Cullum: I started playing pedal steel about seventeen years ago, something like that. I got into it through a lot of British records, mainly sixties pop, not really from country music, but sixties and seventies stuff like Elton John and the Stones and the usual things. Then I was into Beck and lots of indie stuff in the nineties that had pedal steel. I was always intrigued by that sound.

I researched a lot of liner notes on records and discovered a guy in London called BJ Cole. He helped me get my start with pedal steel and taught me how to play. I started working on it in London, which meant I lost my social life. I really dug in. I started playing with a lot of Nashville artists who were touring Europe. I kind of moved to Nashville from that sort of thing. I was getting more work in Nashville. That's how I kind of met Sean (Thompson) and Mikey (Rich Ruth), really, just from being here.

Sam: Was bringing pedal steel to this spacier, more ambient sound something that you had always envisioned?

Spencer: I kind of fell easily into it. We were touring a lot—well, myself and the other two guys in Shrunken Elvis. I invited them to do a European run for one of my projects —a little psych folk project that I needed a small band for. We toured all around Europe in a Volkswagen Passat, all squeezed in together. Rich Ruth would open up the shows, and we kind of segued into making songs organically. We'd put his music into mine, and we started writing songs on the road. It kind of segued into that. There wasn’t much planning going into it, which I kind of prefer. It naturally came about while driving around Germany listening to kosmische music.

My take on pedal steel has never been like, "Oh, it's for ambient music, you know, I'm going to make an ambient record." I feel pedal steel could be adapted to everything. It's such a distinct-sounding instrument that your ears pick up on it.

Sam: What was your experience like moving to Nashville, whether it be culturally or musically? Do you think you could have produced the same output had you stayed in London?

Spencer: I don't think it would have changed, though I think Nashville has helped me develop as an artist and as a musician amazingly. There's such an incredible community, especially when I first moved. It was so encouraging here. It's not competitive, especially when Third Man and the Blue Room came to Nashville. There's such a diverse collection of music in Nashville that isn't just what you see on Music Row.

London... well, it's kind of a cold city. I do miss London. I think it's incredible and I love living there, but it was hard to get on the tube and lug the pedal steel around. I know many incredible pedal steel players in London who play in a different setting than traditional country. But there is also a setting over here that is completely separate from your typical Music Row world. Meeting folks like Rich Ruth and Sean Thompson really sort of reinforced that idea. On my side, there are even songwriters who are not molded into the Nashville stereotype in the sort of way you think they would be. I'm really happy the way Nashville has shaped me. I also like the challenge of Nashville, really. I like going into a country music gig or session and having a chart put down in front of me and having to read it really quickly. There’ll be these insane session guys around, and you have to step up your game. That challenge is something I love about Nashville. Yeah, I'm all for it. It might be pretty fucked politically, but Nashville's a good scene.

Sam: It's certainly a unique city, and much different than other places in the States. It's not a huge city either, compared to other places.

Spencer: Yeah, for example, my wife runs a bookstore, and the community for something like that is really encouraging. You can get bogged down in what's going on in the world, and what's going on in Tennessee specifically, but there is a very strong community that definitely kind of lifts you back up. I still believe there is Southern charm, too!

Sam: How has that Nashville session world rubbed off on you for your own studio sessions? Are there any mistakes or lessons you've taken away from it?

Spencer: It's definitely taught me to be a lot quicker and work at a faster pace. Especially working with various producers in Nashville, I was kind of terrified, going, "Oh, I don't sound like this pedal steel player. I need to sound like this guy." Living here naturally puts you around some insane pedal steel stuff. But it was eating away at me, like, "I can't play a million notes per second."

I definitely had to learn more country riffs and all that here. Now that I've settled into it and become a bit older, there's this idea that I like to share with musicians about being yourself. To be settled in yourself, of your own identity, is such a powerful tool when playing music, even in an environment that you're not comfortable with. I think you get a better outcome with the music if you're confident and comfortable going, "I like this style of music, and I'm very happy to play how I play." I might not get called for every gig because of that. (laughter) But regardless, having your own identity is more rewarding.

Sam: It's really great advice. Especially in country music, which has experimented, of course, but tends to follow a more linear path.

Spencer: It does, yeah. I find that an identity can ruffle some feathers, but it can also make music more exciting. There is this case of the Nashville machine. It feels very plug-in, especially in the session world. It's like "put that there, do that riff, then the same riff goes on that bridge." It can be the most boring-sounding thing. It sounds like Triple A radio, which we've all heard before. But when you're in a situation where a producer wants to go somewhere else, or an artist wants to go somewhere else in that world, it can be really fun and exciting.

Sam: What sort of things collectively influenced the three of you on this record? Was there any idea of wanting it to sound like a specific piece of music? I noticed a lot of Frippertronics and Eno-adjacent elements that seem to have bled into many of the tracks here.

Spencer: Yeah, there definitely was. There's an Ashra record called Blackouts, with a big guitar on the front of it. That was a big record that we were listening to. I know Mikey and Sean are huge Robert Fripp fans. We would go through that sort of Adrian Belew and King Crimson prog phase. I also love the sound of Robert Fripp's guitar playing because it's so intense. There was definitely a drive to get that sound. It's so shrill and harsh, but so beautiful sounding.

Sam: How did the compositions for this record come about? Did you go into the studio with a lot of prewritten tracks or themes?

Spencer: Some of it was written on the road where Mikey had a drum machine. He would lay the foundation for many of the songs. "Marina" was written on the road, and then when we came back, we were like, "Well, let's just record a few of them." We got snowed in one winter and kind of just hunkered down. It was like the perfect time in Mikey's shed—well, shed/studio, I think. I don't think he'd like it being called a shed.

Mikey would write the sort of basics for a lot of drum-heavy tracks. I'd also write some of the more acoustic stuff. But yeah, there wasn't much improvising. Mainly, there was a melody that we'd hook onto and have that repetitive krautrock-y theme. Mikey would lay the bed mainly, but yeah, it wasn't as much improvising. Being snowed in definitely helped.

There was no plan for the record, which I really like. It doesn’t feel forced. That felt really nice, and the fact that Western Vinyl liked it and picked it up was like "oh wow, this is amazing." That's a nice bonus. It makes us feel good.

Sam: What about the name? Where did Shrunken Elvis come from?

Spencer: Well, I'm a little frightened it'll come back at me a bit, but there was a guy in our local pub who used to help out with bands I would be in. He got the nickname Shrunken Elvis. He was a scrappy, shorter dude who was tough as nails. We just looked at him and thought he looked a bit like Elvis. Although I'm not sure he knew he was being called Shrunken Elvis, so I'm hoping that doesn't come back to me.

Sam: Okay, I see. (laughter)

Spencer: But no, you're alright. We also went down a wormhole thinking about any sort of German krautrock-sounding name, and they all just sounded stupid. None of us are from Germany, you know. We all live in Tennessee, so as far as Elvis goes, it does kind of feel related a bit. There is also this tinge of how that sort of prog world can be taken very seriously. It can be a little bit too chin-scratching. So the name, having a pinch of salt with it, is kind of us not taking it too seriously.

Sam: Do any of you guys take influence from the film score world?

Spencer: Oh, definitely. Yeah, we'd love to do a soundtrack for people, obviously. We listened to a lot of Philip Glass, Vangelis, stuff like that.

Sam: In a way, it's very visual music. You can picture potent scenes, which is sort of cemented by the fact that a lot of it comes from those long drives.

Spencer: Yeah, I can definitely see that. Maybe like long drives in a small van, long night drives all around Europe, England, and Ireland, which is all subconsciously steeped into the record.

I don't know if you've felt it, but there's a special moment when you're driving a really long distance—especially out in America, going through the desert or something like that, and you put on Neu! There's that moment—I cannot even describe it—that sort of repetitive motorik beat driving through the desert. Although it sounds really cheesy, I can remember just having moved to America and touring when I was around twenty-seven or something, and someone putting on Neu!, and I was like, “This is world-changing!"

Sam: Those kinds of trips in general are very forcibly meditative.

Spencer: It is! It's like a motorik mantra.

Sam: Were there any challenges in the recording process in terms of keeping the instruments audible and present?

Spencer: Not really, it was insanely easy. We also had as much time as possible to work on stuff and take it back to listen to it. There was the idea, because Mikey's based in the synth world, where I kind of wanted the pedal steel to not be as affected, and it to still sound like a pedal steel. There's some stuff where there's fuzz on it and stuff, but overall, I still wanted it to sound like a traditional pedal steel. Similar to Eno's Apollo, where he likens it to astronauts who are into country music.

I do a lot of sessions where they're like, "Can you make it not sound like a pedal steel?" I'm trying to get away from that. I love the sound of a pedal steel into an amplifier because it does catch your ear.

Sam: How often have you been able to play this stuff live? Is there any tour planned following the release?

Spencer: Not much, honestly. Well, we have like two shows. We have a record release party in Nashville at a place called Soft Junk, then we have one in LA, at a place called Healing Force Records, both in October. That's mainly because Sean and Mikey are both busy out on the road. We're not really taking it on tour as much. I'd love to do some stuff in Europe and play a festival slot at eleven to twelve at night. That's like the perfect time for Shrunken Elvis.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments