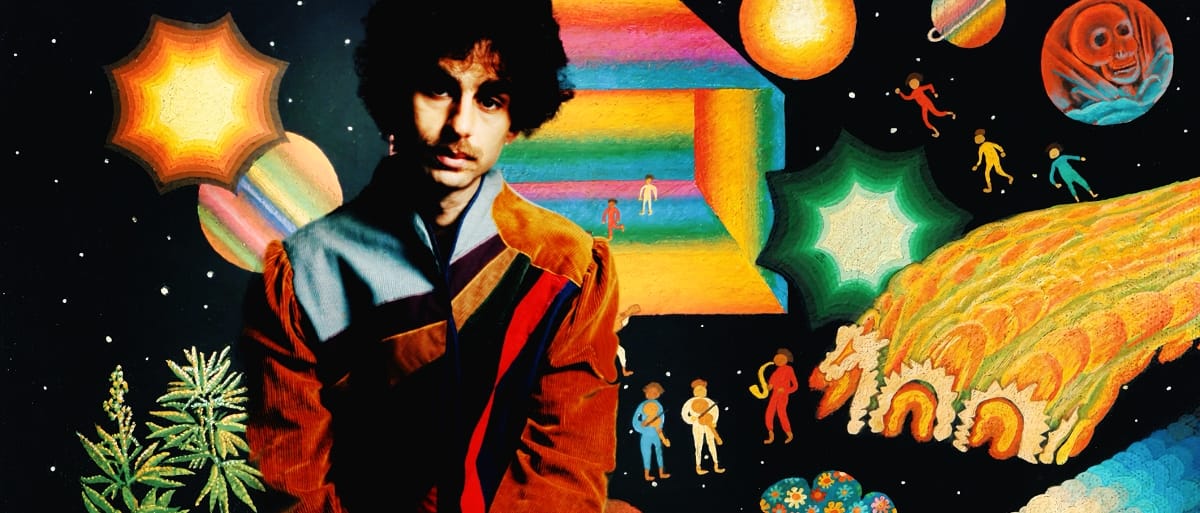

Pain Magazine's debut album, Violent God, is an epithet of two musical acts combining their forces, encompassing their respective core values and sounds. The band is made up of industrial techno duo Maelstrom & Louisahhh, the post-hardcore band Birds in Row, and songwriter Quentin Sauvé. Released on Hummus Records, whose values are community, humanism, and ways for artists to cultivate, share, and exist, Pain Magazine's Violent God digs deep into society's ills in a potent and vibrant way, with a great deluge that is also reflected in their sound and lyrics.

In the song "Dead Meat," Louisahhh starts off with "Passive Aggression was my first love language / A subtle kind of violence." And near the end of "Weak and Predatory," Bart from Birds in Row sings, "My self-esteem—gone / My silly little dream—gone / A bed for when I'm sick—gone / Education for the kids—gone / Justice for the weary—gone." The lyrics amplify their identities, their beliefs, and the urgency of the record, because even when I read or listen to them, I can feel the strain, particularly when Bart sings "gone." The word almost feels breathless, indicating the weight of reality. Similarly, this raspy, guttural question when Louisahhh sings, "Do I believe / In a violent god / You make me believe," in the chorus of "Violent God," the pressure and stress that can be projected onto people's minds and bodies through institutions, interpersonal, or normative, belied action, can be felt. It's not to say that Pain Magazine has it all figured out, but that their strokes of paint feel tapped into these urgencies in a very visceral way.

Acutely aware of subtle violence and violence of all kinds, they are also mindful of their visage as artists in how they allow themselves to create their music so freely. The oscillation and intertwining of industrial techno and post-hardcore then corrals this rage and meditation into what the band is. Off the top of my head, listening to "Bastion," which feels guitar- and drum-heavy, while epic, then listening to "Like a Storm," which dawns a more space-like, electronic feel with less guitar, the album encapsulates a collision of analog and digital. It feels good and super present. "Weak and Predatory" pumps me up with the electronic beat, while "Magic" gets all my punk angst out. All in all, this record is a bright flame of exceptional energy that moves to question expectations, how we self-reflect, all the things that are wrong in this world, and inherently urges ideas of hope, love, and accountability.

Jonah Evans: Mael and Louisahhh, you guys have been playing music together for the better part of a decade, at least. Is that right?

Mael: It's a bit more than that, I think.

Louisa: In February, it's 13 years.

Mael: 13 years. Oh my God.

Jonah: So you guys have grown together as musicians, and you know each other's lives and all that. What's that like?

Mael: It's been a trip, and it's been amazing. I think what's interesting and what's pretty cool is that we come from very different backgrounds in terms of the music we were enjoying as teenagers. Our music cultures were very different. I come from the illegal rave scene of the late 1990s in Europe, sneaking into clubs. When we met and started making music together, we realized very quickly that we were making music for similar reasons and that we had, more or less, the same expectations for the music we were trying to achieve. And these kinds of bonds, I think, have been stronger with the years because we've been sharing our influences and experiences on the road and in the studio. Yeah, it's been a great journey, I'd say.

Jonah: What are some of those values that you guys shared that you bonded over?

Louisa: I think it's very much process-based. And I think the shape of the music industry and where we fit into it has shifted since we started working together. Since we started making music autonomously, the focus on process has become more important because the expectations for external reception of the pieces we're working on are less and less reliable. Whenever I feel like the music industry itself is a catastrophe, and there's no hope for the weirdos, Mael is like, "What are you gonna do? Stop?" I think it's a good attitude because it puts the focus on it not being about the end result; it's about the gift of getting to create stuff with people you love, and that ethos, I think, really transcends beautifully into Pain Magazine.

Jonah: And Bart, you've been in Birds in Row for quite a while. What values did that band establish that you all shared when you first started making music together?

Bart: We started Birds in Row after discovering the DIY scene, like the DIY punk scene. We come from a small town in France, so there was no proper scene—just a couple of people putting up shows. When we started traveling a little bit with our previous bands, we discovered other bands that were actually doing European tours all by themselves. It put things in perspective, like, “Oh, we can actually do that without being famous or anything like that. So let's do this.” And then, the political sense of punk rock came to us when we were playing in community spaces. We learned a lot. I think all our political points of view mainly come from that era when we started traveling and discovering more of the world.

We were already anti-racist, but touring in anti-fascist squads made even more sense to what we already believed in. But the idea of making it a job really scared me. It took me a long time to accept that it could actually be my job, because I was really into this scene where you need to do it for free. You needed to give all of your energy and everything so people have access to cheap culture because it's very important. And so when we started making it a job, it was hard to find the balance between all we believed in and making a living out of it, because we were like 120 days on tour per year.

So, at some point, it means you go home and have to do twice as much work as you should to make a living. It was like everything grew up from . . . I don't want to say 'radical' because I don't think we've ever been super radical in the DIY scene, but to people outside the scene, it seemed radical. Choosing something where we try to find the balance between still having our beliefs and still trying to make a living out of it makes sense.

Jonah: It seems some of those ethical struggles and industry complications are confronted in the Pain Magazine album as well. What got you guys together to form Pain Magazine?

Louisa: Our drummer, Joris, also the producer of Violent God and the brains of the operation, played drums for the Louisahhh live band when we toured from 2021 to 2023. He then gave us really good notes for our first album together and helped shape the kind of three-dimensional mix of that record. According to him, his passion is spending 15 hours a day in the studio and drinking lots of coffee. He's also the drummer for Birds in Row, and he was like, "We're between album cycles, and we're doing a lot of collaboration. Is working together something you guys would be interested in?" And of course, he's a delight, so anything he suggests we're of course into. We arranged a five-day residency that we had hoped would produce at least a song, and ended up spending three five-day residencies writing an album because it went so well.

Jonah: So you didn't know you were going to release an album, then?

Mael: No, we didn't know. All of us had just released an album, so we were still touring the albums we had. We didn't have any pressure to do anything. It was just about trying new stuff. For us, it was completely new to work with a post-hardcore band, and for them, to work with techno people. The whole point of the thing was just to see if we could make music and have fun. I didn't expect us to do an EP during that first residency or even a single track. I thought that we would just get to know each other a little bit better and have some basic loops or a couple of ideas, and that's it. And then after the first session, we had five tracks, not finished, but written.

Bart: I think we were all at the same point of frustration of having to produce music as part of the industry, and so it was like a way to escape all this and just be like, ‘Let's just make music, like we used to do when we were teenagers and trying things in our room.”

Jonah: What was it like in the studio?

Mael: We rented this rehearsal space, which is like a studio, and we had two different rooms separated by a window. One room was Louisa and me, and the other room was Birds in Row, where Joris had some kind of a little production setup. Soon, we started switching rooms and exchanging places within the groups. We never really played together. It was more like production-oriented or jam-based, but never the five of us jamming at the same time.

Jonah: What experiences did you guys have before you went into the studio that informed how you approached the process?

Louisa: I tend to have so much anxiety before going into any new experience about imposter syndrome. I'm the only person who's not holding an instrument on stage, so I felt like I had to prove myself as a songwriter and a vocalist. But the lack of expectations was very helpful; the desire to be in it together, rather than focusing on making this kind of record or this kind of song. There was like so much room to let what was happening be what it was, and I think that led to a really interesting album.

Bart: For us as Birds in Row, we've always had bands since a very young age. Quentin played his first show when he was nine. So we've been playing for a long time, and we know how to create bands. So, if you go into the studio with other people, you know that some dynamics are going to happen. There are ways to fix it. And it's just a matter of respecting each other and creating places, spaces, and stuff. So I was not anxious about that. I just didn't know what to expect. I was actually more excited about the fact of starting something new, and I think it was the same for everyone in the band; it's just, yeah, playing with new people. We didn't get to hang out much, so we were like, "I hope they're nice people. I hope we get along.” After five days, we're like, “Let's do it again and again.” I think it's simple. Like, Louisa told us about her imposter syndrome, but I think it's weird that she's got that.

Louisa: I was really trying to make sure you guys didn't think that I was an imposter.

Bart: But we're all impostors. That's the basis of punk. You don't have to learn how to play music. It's all about putting your feelings in music, and you're very good at that.

Jonah: The album feels like it has a high-level sense of urgency. "Choke Point" is calling out everything, and then "Weak and Predatory" talks about freedom of speech. There are falsehoods and lots of things being called out on the album, and even the sounds of the album, the sensation that I get, like everything feels so immediately urgent and important.

Louisa: For me, the urgency is a baseline, and I don't know if that's a result of how I personally experience the world. If it's not important, then what are we even doing here? It's either like urgency or annihilation; there's nothing in between. There's no mellow zone. If the music doesn't feel like that, then like I'm not doing my job somehow, or I'm entirely disinterested. That’s perhaps not the best way to experience life, but I feel like that's one of the kind of common threads, like that feeling. The sense that the music holds of either being on thin ice or driving at a concrete wall—that's a feeling that both the music of Mael and I and Birds in Row share.

Mael: I think that’s related to the way we produced the record. We didn't pay attention to how it was recorded, and it wasn't a proper studio. We didn't have proper mic stands, or vocal booth, or anything like that. So when we realized the tracks were actually great, and we wanted to finish them, it was too late. Everything that's on there was done in the instant, and that's how we work anyway. It translates into the record's atmosphere, because all the mistakes, all the weird little noises from the room are there. And I think the urgency is there as well. It was like, "Oh, I'm in this situation. We only have five days, and Joris just gave me this drumbeat. What am I gonna do with it?” Everything happened that way.

Bart: Also, the way we would pick up things that we liked or disliked in the songs. If it's not good enough, it's just out. It would be like, "Trash!" (laughter) Normally, it’s like, “Oh, maybe we should try to do something else with the guitar, do something else with the drums, blah, blah, blah.” But for Pain Magazine, it was really just, "Take it off. Take it away. Okay, now do this, do that." And we didn’t care if it was lo-fi or anything like that. We just wanted the music to be sincere and honest.

Jonah: Something I'm finding lately, talking to a lot of artists, is actually the less you think about what you're doing, it’s better for the artistry. Are there things that you learned in the process of making this album that will move forward with you?

Louisa: I know, for me at least, it really speaks to the idea that if you're not enjoying the process, what are you fucking doing? It's easy to get a little anxious about the technical difficulties or spending 12 hours a day recording in a dark room with no windows. But this idea of getting to continue to have a life from music and make music with people that you love and respect and create something that feels like it has authentic truth embedded in it, and that other people are receiving that as truth, there's nothing that I want more on Earth. That's the goal, right? So to get to do that and then have this record received in a way none of us expected is an unbelievable gift. And I think it's just, stay out of the results, stay in the process, and don't forget to fucking enjoy it.

Bart: It's also a good reminder that if things go pretty well and people listen to it, you should only focus on doing the music that you want to do because that's what people are expecting from you. But it's hard to get in that zone sometimes because you have pressure to put out four or five singles before the album comes out, and so on. If it were just me, I would release the record the day that we had the master.

There are so many things that make you bitter when you get into this industry that you tend to forget what's most important: enjoying playing music and the magic of creating music with other people. And the magic gets even bigger when you tour with a record and play those songs, and people get to talk to you about what they feel when they listen to those songs. I think just the moment where you get out of the room, and you're like, “Whoa, this is a song that we've just created.” It's truly a gift for me.

Jonah: Louisahhh, I saw that you admire bell hooks. What is it about her philosophy of humanity that you carry with you?

Louisa: I love the way bell hooks writes and how important teaching is to her, and there’s nothing that's finger-wagging about it. It's like there's so much inherent love in these often challenging messages that she delivers. And I really like being grounded in the idea that it will not be easy, whatever move towards liberation, but it is possible, and we can hold space for the challenge. This idea of instead of shying away from the feelings that come up surrounding like shame or anger or anything or grief—this record has a lot of grief in it—to be like, "No," this is where I need to go in order to be in relationship or be present with what we're making or even be in a band, and hopefully carrying that willingness to do the hardship will help us live through this fucking horrendous political moment.

Bart: I don't know about bell hooks. I'm not a big reader, but most of the books that I read are political and sociological. And I think everything that I learned from what we do and the big thinkers—Emma Goldman, for example—are, to be fair, usually anarchist or communist. This idea that there is no merit and there is no talent, and that's the thing that I want to transmit to people, if it makes sense. It's not directly linked to one person, one philosopher, or anything like that, but I talk about how talent is usually a class thing. I like to remind people by just being on the road, telling them that a small band from a small town in France actually has a little bit of recognition, and that it should be a good example of how anyone can do the same. I hope that people understand that. That thing pretty much saved my life, and I hope it saves theirs, too.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmJonah Evans

The TonearmJonah Evans

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments