The first time I saw the late guitarist Davey Williams improvising on his Steinberger, I chortled to his warped boogaloo. After a moment, the smell of the grass and the crack of the bat that is our national pastime encroached. After that—heck, after this—I should have been punched in the face. This feature isn't to reflect upon Mr. Williams; then again, he serves as a timestamp, a through-line connecting then to now and what's to come for the guitar. Specifically, for the role of improvisation inside a rock and roll framework. Enter Bill Orcutt's Palilalia Records, itself an exit from prison stretch since 2009, bringing the noise and guitars.

Ooh, stop.

With my original intention of interviewing Orcutt concerning his propensity for releasing mostly guitar music on Palilalia, and within forty-eight hours of pitching this plan to The Tonearm, news spread that the recording titled Orcutt Shelley Miller was being issued on Silver Current. My reorientation wasn’t automatic. I read the press release; I’m not so sure my assumptions about “underground rock trio” were three words any readers were expecting to have just read.

Some backstory. After a baker's dozen years into the American underground music scene, I found myself gravitating far away from the power of electric guitar in ways Van Halen, the James Gang, and ZZ Top had permeated FM radio and my adolescent years. Beyond Greg Ginn, J Mascis, or Curt Kirkwood.

I especially loved those SST players, their bands (trios if you only count instrumentation), but other approaches to the instrument suited my evolutionary strides. Matthew Bower's projects, Brother JT and Vibrolux, the aforementioned improvisational playing of Davey Williams, the Sun City Girls' Richard Bishop. Harry Pussy was taking it to the streets of Miami, just south on I-95. You may rightly surmise Sonic Youth was my North Star, granted, not a trio. My listening was carefully curated. Or produced… umm… I directed a sort of personal In Search Of.

Lo came time passages, births and deaths. I now wear my trousers rolled.

The frame narrative for rock guitar, the rock trio, the power trio, whatever the tagline, is for many fixed in time like imagined high school parties when spin the bottle was played with the class brain's eyeglasses.

Ethan Miller's Silver Current label is unashamedly committed to reprising and celebrating rock and roll. His own band, Howlin' Rain (among labelmates), pinpointedly references rock's origins in blues, folk, and country. The releases are rather straightforward and sundazed in homage to legends and consistently engaging. Songwriting chops and scorching solos are expected. Orcutt Shelley Miller is slightly askance. This aligning of players alludes to that sixties jazz trope when a musician could be both a group member and a group leader. Think Tyner and Coltrane and the freedom of musicians to move and groove across Blue Note to Impulse! and even ESP.

I opened our group email interview thusly: Your names are not alphabetized on the jacket, the record lacks any other title, and it's not a Palilalia release, which had been my expectation upon learning of this record. How did this trio come to be? Does a leader exist for this combo? What was/what is the plan?

Ethan Miller: Harry Pussy had been on my periphery in the late 1990s/early 2000s, and when Bill started playing live again, I was around on the scene in SF to catch a lot of early shows and his immediate post-return musical evolution. I became a fan. In 2019, I invited Bill to be one of our guests on a concert in SF for the fiftieth anniversary celebration of the Grateful Dead's albums Aoxomoxoa and Live/Dead, which I was band leader for. Even though he wasn't much of a Dead fan, he was enthused to partake, and he did "Death Don't Have No Mercy" with a full band. I'm not sure if he clocked it or not on stage in the moment, but he just floored the audience when he lit into the solo. My wife told me later that the people around her in the audience were just like, "Holy shit!! Who the... What the... Wow!!!" when he lit it up.

The next day, he told me how much he enjoyed playing with a band behind him and that he hadn't really played with that kind of rock band since high school. I suggested we invent a project of some sort, with a rhythm section, maybe something that nods toward outer seventies krautrock or free fusion or acid rock or one or all of these kinds of musical subgenres that we both mutually appreciated. He said if I could figure out the organizational end, he'd do it. Somewhere in there was also the understanding that I'd get to put it out on my label.

In March of 2020, we finally had a show set up to do this. A few days before it happened, California went into total pandemic lockdown, and the show was obviously cancelled. We kept in touch through the pandemic and kept a real, real low-burning flame for the project somewhere way on the back burner. In 2024, I asked if he was still down to give the project a try, and I suggested Steve Shelley for drums. I’d been working with Steve the previous year or two on the Sonic Youth Live in Brooklyn 2011 release my label Silver Current put out. Bill said yes, Steve said yes. I booked us two studio days at Eric Bauer and John Dwyer's studio in Los Angeles, without the three of us ever having played a note as a trio.

It was Eric Bauer, the engineer, who suggested we do the third day as a live performance at Zebulon, where he knew we could multitrack. Because it was going to be based on improv, that seemed like a great idea and kind of ingenious that we'd be getting paid for the third day of album recording instead of paying a bunch of money. We came out with a ton of recordings from the first two studio days that would need to be edited and potentially constructed into a final form for an album, but of course, the third day, the Zebulon show, was the distillation of a lot of those ideas in a pretty much finished or at least highly spirited form. In the end, we just used that as our debut album.

Our names are not alphabetized because we decided we wanted a band name that looked like a single name. I think I suggested that order of names as the band name. I was working on artwork layout and the stamp for the front cover, and I thought 'Orcutt Shelley Miller' had the right flow and look, you know? Like Nash, Stills & Crosby sounds like a bunch of dorks. Total fucking dorks. But Crosby, Stills & Nash sounds like a bunch of hippie badasses. They almost sound like a gang of barbarians that way, just based on the name flow. Who knows why? And I think we wanted to take it one step further than the barbaric Crosby, Stills & Nash and have no commas and no 'and' or ampersand. Just Orcutt Shelley Miller—one name like it could just be one weird person, like the three of us walked into the teleportation pod and only one fused thing walked out and said "Hi, I'm Orcutt Shelley Miller," and it looks all fucked up like Brundlefly.

We don't have a leader; we're just playing off each other. Same with the workload and decisions. I think on stage or studio, our ears are open to a new idea that someone may throw down for the other two to jump into. And the throwing down and pushing forward seem to move around the circle pretty freely. I personally feel like the anticipation of music and the creative electricity inside that circle of our band in performance is pretty charged. It's a place where I certainly don't fear the outcome of nothing is happening.'

So much is happening, especially given two days of studio time preceding the 2024 Zebulon live recording, which brought to bear the players' gifts, specialized and readily identifiable. Miller's hunch to ask Orcutt aboard for the Grateful Dead celebration was fortuitous.

With both Orcutt and Miller residing in Northern California, the nods to the Bay Area's sonic legacy were unsurprising, even if Orcutt wasn't as regionally steeped as Miller. Recall that Sonic Youth's Lee Ranaldo was a known Dead friend. Was this a secret Shelley interest, too? I never asked. I had more questions for Orcutt, who was wrapping up his own tour.

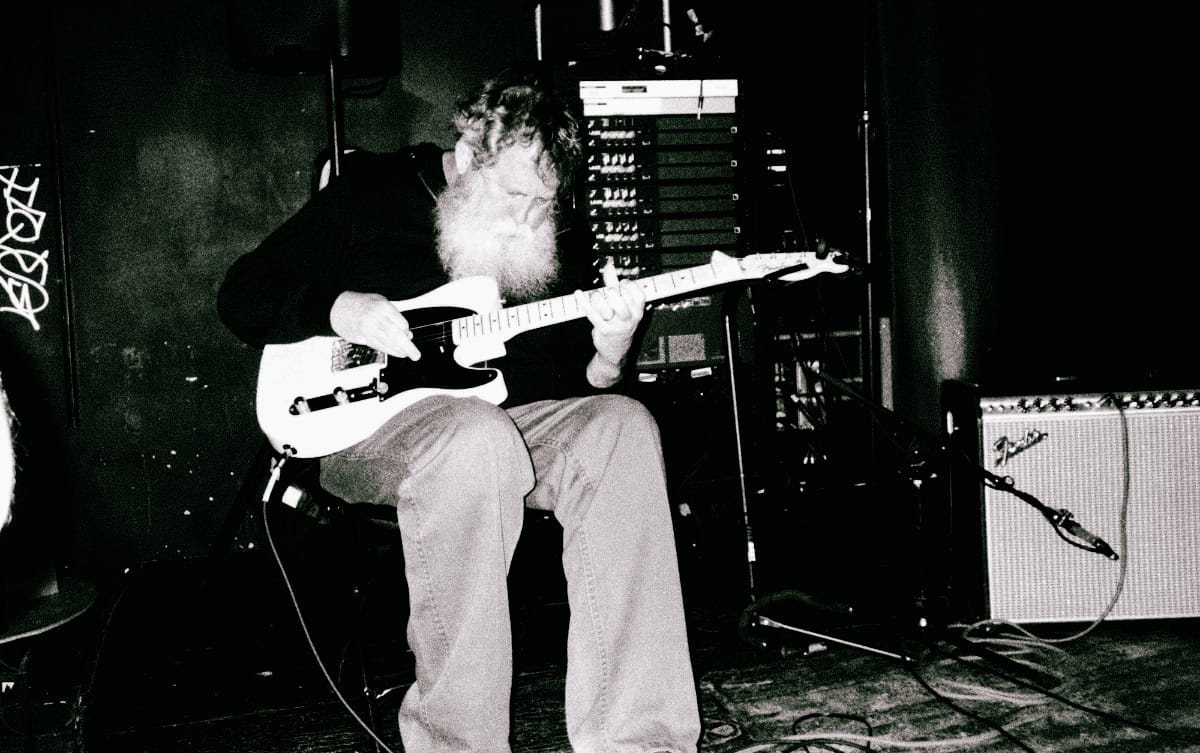

Garnett: Bill, I just listened to the 1985 sessions of your first high school band you uploaded to the Palilalia Bandcamp page. This group had the chugga-chugga sound; certainly, the band wasn't afraid to ironically or otherwise boogie. I'll use your return to the public via that solo album's title, A New Way to Pay Old Debts, as a way I choose to hear your playing since Harry Pussy. You keep resuscitating the guitar, inviting folks onto Palilalia who are doing the same. How do you suppose the guitar survives for yourself and with this trio?

Bill Orcutt: I'm not aware of resuscitating anything, really. I just enjoy playing and finding new ways to surprise myself. It all happens organically. There's not a lot of strategizing that goes into it. There's no plan. I love the history of the guitar and of guitar players, so it's a conversation I want to be part of.

All were asked what's next, what could be different if there's a next, and doors were left open.

Bill: There's a ton of material from those two days. A ton! Hours and hours. Multitrack. Is it any good? I dunno, maybe… I haven't listened to it. Ethan sings! Maybe he can be a future vocalist. I don't really have a familiar framework, so it's all just an adventure to me. And it's only music, not mountain climbing, so there's no risk of permanent injury. It's all about fun.

I love rock and roll.

I was most familiar with Steve Shelley's decades of drumming with Sonic Youth. His catalog beyond Sonic Youth is also impressive. I had some questions.

Garnett: From EVOL to now, I recognize your drumming, and this across ensembles. To me, drums have functionally been your voice across four decades. You consistently appear pleased or happy when playing. Engaged, locked in, perhaps in abandonment or complete surrender to the music—maybe even joyful. Do you play another instrument? I've never seen you not into the job of drumming with complete gusto as you are here with Orcutt and Miller. What's the magic?

Steve Shelley: I hear that from time to time—people catching me grinning while onstage (another reason I'll never be invited to play with the Bad Seeds). If confronted, I usually deny any degree of joy or happiness—the material is so serious, the work is so hard!—but yeah, you caught me smiling again. I'm stuck with the drums, and I enjoy the problem-solving and architecture of whatever it is that different musical combos will build. I think I enjoy combos the best—listening to the instrumentalists (and vocalist) communicate with each other.

Garnett: Do you find refreshment in removing expectations from yourselves and others when collaborating outside familiar frameworks? Does the spontaneity of the Orcutt Shelley Miller record run a risk of not holding a royal flush?

Steve: Well, I'm hoping for a royal flush every night—no matter who I'm with (some would call it delusions of grandeur)—but a beautiful part of what we do is the uncertainty of what will happen on any night.

Song titles like "Unsafe at Any Speed" and "Four-Door Charger" and the hasty creation of a standout record brought to my mind the great American road trip. A movie like Two-Lane Blacktop, the kicks on Route 66, what you conjure in a flyover state, or didn't know you'd overlooked at forgotten roadside attractions. That's a lot of miles. Drivers should take turns. Arrive alive.

At points, each member is the wheel, is behind the wheel. It's chrome-plated, sporting new tread and struts. Orcutt Shelley Miller includes repetition and resolutions, peaks and valleys. Forward through the heat haze, but not quite to "Let's get lost," but I don't know. If you know the players' discographies and the personality and talents each has demonstrated across decades, be prepared to hear each in new ways and to be surprised and pleased.

This is now American music. Fueled and waiting. Long may they run.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmMichael Centrone

The TonearmMichael Centrone

Comments