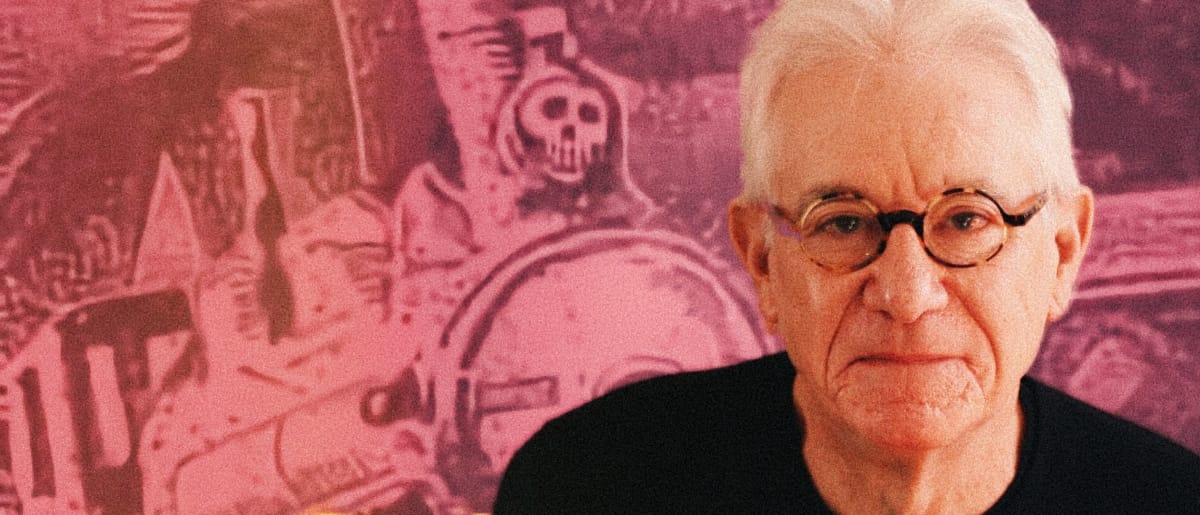

Ludo Hunter-Tilney is a London-based music journalist who writes for the Financial Times. His first review was published in 1998 (for Dr. John's album Anutha Zone), and his first interview was in 2002 (with Marianne Faithfull). He won the London Press Club's award for arts reviewer of the year in 2014. He has also written for the New York Times, The Guardian, and the New Statesman.

I've been a fan of his work as a critic for a long time. His balanced and consistent reviews offer a different perspective and always inform the music reader. As a critic, he often displays his knowledge as a music historian, for example, in his New York Times article on Art Gillham, a musician known as "the Whispering Pianist" for his gentle croon, who was the first to record vocals using a microphone.

He can be witty, without the snark. For example, where he commented on AC/DC, "Watching the antique Australian hard rockers perform is like witnessing a venerable but tedious ritual with scant application to the modern world: heavy metal's version of Trooping the Colour."

But in the age of algorithms, music writers are a valuable alternative, and Ludo, in his role as a critic, offers analysis, context, and popular commentary on a wide range of music. What I appreciate is how he tackles each genre with the same level of professional commitment, whether it's rap, TikTok stars, pop, K-Pop, classic, or indie rock.

After following each other online for a while, I responded to one of the articles he shared about music discovery, an area of particular interest to me. "Despite having access to more music than ever before, many of us are still falling back on the same old stuff. The algorithms may be pushing us toward uniformity, but how do we break out of the echo chamber?" I shared one of my articles on a related topic, and he responded, to my surprise, which encouraged me to engage in more music discourse on the social network.

A stray tweet of his about a newspaper article from my hometown caught my attention, and I decided to reach out to ask whether he was visiting. I plucked up the gumption to arrange a meet-up. We had a very enjoyable conversation about music and followed up a few weeks later for a more in-depth talk.

Damien: One thing I find interesting is your title as a Pop Critic—popular culture is such a wide-ranging subject. Looking back over all the articles you've written, there are many I can pick out. There's also a long-form piece you wrote in the New York Times on the invention of the microphone that I really liked.

But you've written on K-pop, rap, pop, rock, alt-rock, and multiple other genres. You field everything from obituaries to Taylor Swift. It's so wide-ranging.

Ludovic Hunter-Tilney: I think being able to write on a wide range of things is something I've always wanted to try to do, and popular music really does allow that, doesn't it? I've become more aware, I suppose, that it's popular music, which makes you sound like a fuddy-duddy when you say that. When you say you write about 'popular music,' you're at risk of sounding like you're from the nineteen-fifties. But it's a much closer term than 'pop music,' which can obviously refer to a very specific type of popular music. So I think of myself as ranging quite freely through popular music, trying to cover all the various ways it goes, and popular music opens you up to anything which is basically popular.

Damien: In those formats, whether it's long-form, obituaries, gig reviews, interviews like with Robert Plant, or coverage of a festival like Glastonbury, which format do you like to write in the most?

Ludo: I think of myself mostly as a critic, which would place the album reviews and the live reviews at the forefront. But in truth, I take great satisfaction in writing a good feature. A feature has a range of different people you've interviewed, which I don't find particularly easy—I find them quite stressful: the idea of just tracking down lots of different people, getting all their voices, and then putting it all together. I suppose the feeling of achievement there is great that you've managed to create this collection of different things.

And an obituary, which obviously I've done more of because there's such a call for those, has its own feelings of satisfaction, I suppose. It's a responsibility, isn't it, that you're actually holding someone's life in your hands. Not to sound too grandiose, but that big grand term for journalism as the first draft of history applies particularly strongly to the obituary.

Damien: So you want to do them justice, basically? Someone like Ozzy Osbourne, for example, is an interesting character who has led an entertaining life. I understand the responsibility you want to capture some humor in there, without being overemotional. At the end of the day, he's a wild person, and he wants that to be captured.

Ludo: That's the balance, isn't it? I think one thing about music is that it commands such a strong emotional response from us that the people who trigger these feelings become very important, which in a way might not be the same with a film star, as much as we might mourn their passing. There's also the fact that we listen to music most intently when we're young, when we're formative people ourselves. I think there's a way in which music is such an important part of who we feel we are and our emotional response to it. All of that comes together when writing about someone's life. You want to be able to touch that chord in people who will be reading it, whilst, of course, also being true to the life, which might necessarily be a complicated life. It might be a sad life. It might have other things in it. And then, I suppose you want to bring out some of the incidents and even the humor. Music and musicians can be very good material for that because they tend to lead quite incident-packed lives, let us say.

There tends to be quite a lot of anecdotes, and there's a lot of rock mythology that will amass around someone like Ozzy Osbourne. You just can't fail to drop in an incident from his life, which will add a lot of color. And, with a lot of musicians who generally have a reputation for being quite tongue-tied and inarticulate coming alive when they've got their instruments or at the microphone, lots of them speak in a really engaging and funny way or in a way that is very quotable.

Damien: Is there an interview that has genuinely surprised you for good or bad reasons?

Ludo: I've got to think about that because I've done a million interviews. I try to go into an interview not as someone who might be a fan of the person's music. It's impossible not to, if it's someone like Robert Plant, who I really admire. It's not like a fanzine. You're writing for an audience who might not know about this person or might not be particularly interested in this person. I do try to dampen that down.

I think in terms of being a surprise, I don't feel I've ever had interviews that have gone severely wrong. Well, maybe one or two! So no, I don't think that there's ever been a surprise—that sounds like an odd answer, doesn't it?

Damien: Well, the same type of question, but for gigs or live performances. Do you find it hard to write negatively about live performances and artists?

Ludo: I would always prefer to write negatively about a bad performance. I mean, that's just the job, isn't it? You have to do that. If you see a bad performance, you have to give a bad review. I actually think there are fewer bad performances—you just see fewer shambolic gigs that fall apart.

I remember seeing The Fall play in their later years, and there was Mark E. Smith going around turning off all his bandmates' amplifiers, chucking microphones into the crowd, and disappearing after about twenty minutes. There were all the usual Fall fans, but there were a few younger people, too, who seemed to be drawn by the curiosity of watching a gig be shambolic. It does get slightly harder than watching something and thinking that's no good, even though someone's trying to do it.

I went to Fontaines D.C. at Alexandra Palace, and I didn't really enjoy it. I found myself becoming increasingly more disengaged. They didn't play badly, and the audience of 10,000 loved it, but they didn't quite convince me. I suppose that would be an example of somewhere where it was, by most accounts, people there were having a good time, and the songs they were playing weren't full of mistakes. But I just didn't really get with it. I didn't really believe in them, I suppose, or their performance as a result of that.

There's too much music out, and a lot of it's three-star music. I'm a three-star person. I don't claim to be much more than that. But when you're listening to something, and you're going to see something, you don't always want to be reminded of the three-starness of life.

Damien: This brings me to another point, because you've been with the Financial Times for more than twenty years at this point. You've seen a full twenty years of digital music. The promise of the democratization of music, where the entry barrier was lowered, allowing musicians to make music in their bedrooms with advances in technology, pedals, software, and digital tools. But we ended up with an oversaturation of music with no way to filter through it because we've just been following streaming platforms and algorithms.

When it comes to music discovery, how do you find it yourself? Or does music come to you for review, or do you pitch what you want to write about to the editor?

Ludo: I'm sent a lot of music, a huge amount of music, and there's such a profusion of it. As I said, a lot is fine. It's not like lots of bad music. There's lots of fine music, and there's lots of music in genres you could really get into, but it is too much to keep up with. You could drive yourself mad. I mean, I could literally spend an entire week listening only to the music I've been sent that week and then responding to the publicists who sent it to me. That would literally be my job, except, of course, then I wouldn't be paid. I would probably end up being some lonely figure in my garage getting madder. So you can't keep track of it all; it's just not possible.

In terms of my practice at the FT, I do two album reviews a week and live reviews on an as-needed basis. I think that at the moment, there's an attempt to broaden the music coverage, so it's not just rooted to albums and gigs, to try to introduce other things. What I would really like is to write about new music. One problem is that we have too much music, and another is that newspapers are now tabulated to the nth degree, just as what we listen to is on platforms like Spotify. So it's known how many readers will read your piece and how long they'll read it—how long their precious eyeballs have spent looking at your 400 words on the latest album by Kid Harpoon.

I think there's a problem that readers read the big names. I have readers who want to know about the latest music, and others who want to know about Taylor Swift's new album. And then readers who want to know about Taylor Swift's new album will outnumber the ones who want to know about new music. Although the ones who want to know about new music are constituents I would always try to keep in mind, too. These are the music lovers, and you want to introduce them to new things.

You'll see comments below the reviews from someone saying, "Oh, I've listened to this album, so thanks to you." I love it. That's my favorite comment. That's great. I've done something, you've listened to it, and you've really liked it. It's great, isn't it, when you can direct someone somewhere?

Damien: I'm curious about some of the journalistic tools that you use and how they've changed, whether it's a laptop, the digital assistants, or software for transcribing interviews. How has your day changed? Has it changed a lot?

Ludo: I've been doing this for over twenty years. My first review was written, to be precise, in 1998, and it has grown in volume from there. So yes, it's been a long time. There weren't mobile telephones and such. At times, I feel like quite an ancient pop critic. I even feel a bit like the Methuselah of pop critics, the oldest of all, as I drag myself off to some gigs.

I use a pen and paper for making notes. Old-fashioned reporter's notebook or something like that, or whatever it might be. And I make my notes, and I'm one of the last of the breed to be bringing out these antique implements. Everyone else makes notes on their smartphones. I find using a phone off-putting. I'm not very quick at tapping, and so it just becomes that glowing screen. Whereas I'll make my notes, and I won't look. And I do find that they're indecipherable afterwards. I'll look at them like, "What on earth am I on about?" It's like a private language which has become a private nonlanguage, I suppose you would say.

I've always written on the computer, that's true to say. I've never actually 'written'; I've lost the ability to write using pen and paper for reviews or longer pieces. I've been completely attuned to using a keyboard, so I don't think I could do that anymore. That's how the machines we use to write can end up taking us over.

At the risk of sounding very pretentious, I think Nietzsche was one of the first writers to use a typewriter because his eyes were going. He was getting used to typing, and he noticed that his writing became much more telegraphic and shorter. It changed style quite considerably, and he realized that the typewriter had reformatted his writing consciousness. Anyway, I use a computer, despite that pretentious little aside. I always have.

When it comes to transcribing, again, I'm old-school. I do that, and I hate transcribing. That's the part of my job I dislike most: listening back to yourself for forty-five minutes or an hour. And you have to. I don't like to listen to my voice, which many of us don't, listening to my tones fluting away. And then your interviewee makes some interesting points, and you cut them off; or they're just about to do something, and you take them off course with a question. Anyway, I hate it. It's like self-flagellation, frankly, and I'm very slow at it. But I'm drawn back to it. In some ways, I feel a sort of moral compulsion that I have to listen back to it to write about it.

Everybody else that I know now uses software. And they're always saying, why don't you use this and why don't you use that? And I just can't bring myself to make that final leap, and I don't know why it is. It is a slightly strange mentality that I've got myself into there. I think you need to listen back so you can hear everything and re-experience those mortifying feelings to get a deeper sense of how that interview went and to work out your ideas. I don't think that's the best reason not to use these things, but anyway, that's the one I give.

Damien: There's a piece that I read that stuck with me that you wrote a few months back, where you say, "music has the best claim to be an agent of change." Do you remember that piece?

Ludo: I think that piece that you were kind enough to quote was about Kneecap. I was thinking about one of the founding myths of Belgium in the nineteenth century: a bunch of people in an opera house were so moved and inflamed by a nationalist song being performed that they marched out. The next thing is they've taken the city in the name of what will soon become Belgium itself. Unlike Verdi, whose arias were fundamental to Italian nationalism, there it seemed that the actual music is something because it moves us, in a way that can get under our skin. It's a very strong way to establish a joint communal identity. For me, music does have this claim above the other arts as being able to effect change.

I contrasted that with the postwar claims. You then think about things like punk. I thought, though, has there actually been such a great deal of change? I was trying to work out how much we have of this idea of protest music, how much it brings about change, how well the protest works, and how much we enjoy it as music.

Music is caught up in a record-label–led structure that is adept at marketing and selling forms of rebellion to people. It's a monetized rebellion, to use a lovely way of putting it. So, how much can it change now? I did take a slightly cynical view in that column that, at a time we think would be the most political and active—in other words, in the post-rock and roll era—you could say that opera was much more important in the nineteenth-century context.

But everywhere's different, isn't it? You've got a great resurgence of protest music going on in Ireland at the moment, and Kneecap is part of that resurgence. There are ways in which Irishness has a musical identity, and it's complicated by the fact that lots of those acts use English, but there is, of course, Irish as a language, too. How does that fit into music? And, of course, there's been a long history of music in Irish and so on and so forth.

But you can see, then, that these are all up for grabs. Music plays a role, and there are forms of change coming around. Obviously, Ireland's a very different country now than it was in 1971 when we were born. And in the British context, I would say the same. I mean, it's harder to gauge in Britain, I think, in some ways, because the country's so much bigger, a country of 70,000,000 people, a country which, moreover, is made up of different countries. That's maybe one reason my column ends up more like that: I just think it gets harder to work out. You can't read through so easily, is what I think. Then you would think back to things like Britpop, a totally other era in terms of how we were thinking about music.

Damien: Speaking of Britpop, you went along to Oasis this year?

Ludo: I saw Oasis in Cardiff. It felt like a very big occasion, big in every single sense. Streets thronged with loads of Oasis fans. The Millennium Stadium is slap bang in the middle of the city, Oasis fans everywhere, bucket hats galore. Then their sound was huge, loud. It was the big sounds of the mid-nineties. I was struck by that nostalgia. I've always felt suspicious of the nineties' nostalgia, the era when we were in our twenties, which is very easy to be nostalgic about. But I thought that nostalgia was completely transformed by the number of younger people there who were really into it and knew all the words. The whole sense of generations being in battle, having a go at one another, which we would have had in previous decades—it wasn't there at all, and it made it much better.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmAndrew Hamlin

The TonearmAndrew Hamlin

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments