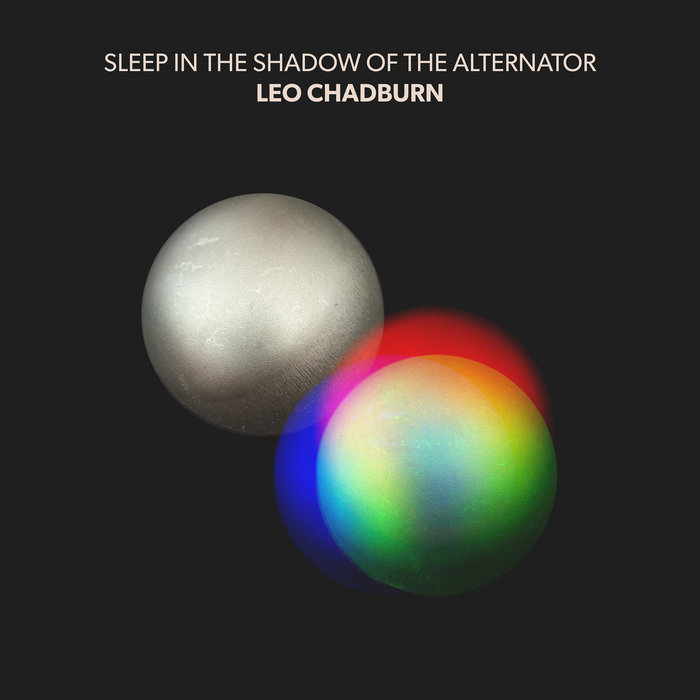

Leo Chadburn's new album is based on his near twenty-year background in experimental, avant-pop, art-rock, and neo-classical music. Growing up in the historic coal-mining town of Coalville in the East Midlands of the UK, Leo moved to London to study music. He began his career as alter ego Simon Bookish, focusing on left-field indie-pop on Germany's Tomlab label. Now, on his eighth album, the fourth as Leo Chadburn, he has created Sleep in the Shadow of the Alternator, a four-part spoken word/poem as a commentary on industrial decline, accompanied by electronica and a PhD attitude.

Chadburn describes Sleep in the Shadow of the Alternator as "a radiophonic lullaby for a half-forgotten place and time." The album's four tracks unfold across changing seasons, incorporating close-miked spoken word through slowly revolving harmonies, electrical drones, and the distant rumble of metal percussion. Chadburn performs on an arsenal of instruments ranging from bowed vibraphone and thundersheet to shortwave radio and prepared piano, creating what he calls a "labyrinthine narrative" that transforms memories of East Midlands industry into dream logic.

The album's science-fiction finale imagines a post-human England one thousand years hence, where traces of industrial civilization have nearly vanished beneath reclaimed wilderness. This vision—part melancholy, part wonder—captures the peculiar alchemy of Chadburn's work: the ability to find magic in the mundane, beauty in decay, and universal truths in specific places. By treating landscape as both subject and sound source, Chadburn sits within the lineage of British experimental artists like Delia Derbyshire and Derek Jarman. It's time to wake up and smell the AC, and get to know Dr. Leo better.

My illuminating chat with Leo Chadburn has been lightly edited for clarity and flow.

Gerry Hectic: The press release mentions you've been featured on Resonance FM. What was that for? Was it during your synth period?

Leo Chadburn: Music of mine has been occasionally played on various shows on Resonance FM over the years. I also recall presenting a show, many years ago, with curator Cecilia Wee. Coincidentally, I've just finished recording a script for the composer Neil Luck at the Resonance studios, which will be broadcast later this year.

Gerry: I used to love tuning in to Resonance FM to catch shows featuring SpizzEnergi, Jonny Trunk, Robin The Fog, Art Rocker, Intoxica, Lucky Cat, Nostalgie Ya Mboka, and many more.

Leo: I'm a big fan of radio as a medium, and a lot of my work has been on the fringes of experimental music, so I guess it's inevitable that some of it would end up on Resonance, which has been an extraordinary supporter of left-field art in London and the UK. We're very lucky that it exists and continues to be a beacon of radical thinking about what radio might be.

Gerry: On the topic of radio, I see one of the instruments you play on the new album is a shortwave radio.

Leo: It's full of interesting sounds, including a lot of alluringly strange noises in between stations. I'm certainly not the first musician to use shortwave radio as an instrument—Stockhausen wrote a sequence of pieces featuring it in the late 1960s—but it seemed appropriate to have it on this album, which is so inspired by the sound and forms of radio.

Gerry: Speaking of radical thinking, I'd have thought the world needs more ‘big bands performing song cycles about science and information.' What's the difference between Leo and your earlier incarnation as Simon Bookish?

Leo: I did many performances as Simon Bookish in the mid-2000s, with the intention that the name would separate my more 'pop' work from the more experimental music I was also making. Inevitably, though, the boundaries were always a little blurred, and I released the last Simon Bookish album in 2008.

Gerry: Everything/Everything, on the face of it, was strange avant-pop classical OST music hall that possibly needed a John Peel type of DJ figure to champion it.

Leo: Quite deliberately, it was a musically extravagant album, despite being made on a very modest budget. Lyrically, it covers everything from the evolution of language to the end of the world, and it takes a magpie approach to style—elements of motorik, disco, chanson, minimalism, jazz, Zimbabwean music, plainchant. I was trying to cram in every idea I had. The unifying factor was having an explosive brass and horn arrangement on every track, as if every song were in Technicolor. The key inspiration was Peter Greenaway's similarly overstuffed film The Falls.

John Peel was no longer with us when that album was released, but it's nice to think he might have been interested in it. Another brilliant broadcaster, Stuart Maconie, is a fan of it, though, and has played it on 6 Music now and then. I think the prog elements appeal to him.

Gerry: The new album is quite different from your last one, as Leo Chadburn, The Primordial Pieces. That one came out last summer with a modern classical theme featuring traditional piano and violin, and was released on the same label as the new album. How did you suddenly think, "I've got an idea for a four-track spoken word, experimental album where I play all the instruments"? That would be a jarring change of style for most labels.

Leo: Well, Library of Nothing is my label, so the only person I need to persuade that my music's worth putting out is me—convincing oneself is not necessarily straightforward, of course! I've released music on my own label since the final Simon Bookish album, which was on Tomlab Records, also the original home of my friends Owen Pallett, Patrick Wolf, and a really brilliant roster of strange pop: The Books, Xiu Xiu, etc. Tomlab was wound up a few years ago, I think.

I'm a big advocate of setting up your own label, for exactly the reasons you allude to in your question. I like to change my mind, to explore music from a different angle each time I make a record. It's fairly hard work, of course, but being in control of the artistic direction from the beginning to the end of the whole process is a thrill.

Gerry: The opening track, "The Body Becomes a View Finder," seems to be a look back at your youth living in the East Midlands, which is, like you say, intensely industrial and urban but rural within half an hour radius—especially mining areas that are often in the countryside with a big railway network next to them: South Wales, Kent, Nottinghamshire, the Northeast, Scotland.

Leo: Yes. The town I grew up in, Coalville, was—as its name suggests—completely defined by the mines and heavy industry. But you can walk twenty minutes out of the center into Charnwood Forest. I went to school on the edge of town, immediately next to the Warren Hills area, which is covered in some of the oldest rock formations in the UK. Only slightly further away are very beautiful natural landscapes: Bradgate Park and Beacon Hill.

That tension between industrial and natural landscapes was the starting point for the album's imagery.

Gerry: This theme is picked up with "Magic Flora of the East Midlands," which sounds like it should be a book of herbal apothecary by Julian Cope—a longtime resident of Tamworth, which is nearby—in a monastic chant of ancient to industrial trades set to warped electronica. You’re joined on this track by George Barton on glass chimes and mark tree, a percussive instrument devised by Mark Stevens in 1967, also known as bar chimes. Is this the closest you get to Ivor Cutler and Tangerine Dream?

Leo: I don't feel that I know Tangerine Dream's work well enough, but obviously, any music with a quality of 'rhythmic drift' appeals to me. I wasn't actively thinking about Ivor Cutler while making this, but I love his work and believe him to be a genius. Cutler has this ability to transform something mundane into something surreal and magical. I suppose I was aiming at something similar with "Magic Flora of the East Midlands": suggesting a kind of mysterious, transformative incantation of this list of plants and list of obsolete occupations.

Gerry: To cover the transport links of the region, "Move Like a Freight Train" seems to incorporate more instruments and has that hypnotic train beat to it—almost spoken word poetry or organic techno.

Leo: The album draws on quite specific childhood memories of being allowed to visit two industrial sites. The first was the Falcon Works in Loughborough—the iconic "Brush" factory that still looms over the railway station—where they manufactured electrical switchgears, transformers, and rolling stock for the new Channel Tunnel. In essence, a factory filled with giant machines that made even bigger machines.

The other was a visit to the open-cast mine on the edge of town. The deep-level mines had been closed under the Thatcher government in 1984, but the open-cast mines were in operation for nearly another decade. They took eight million tons of coal out of a vast pit, using dragline excavators the size of skyscrapers.

Since I was so young, and these places were so dramatic, intimidating even, my memories of them are hazy. It feels as if I might have dreamed these places. That's what "Move Like a Freight Train" is about and what the album is more generally about: the slippage between dream and reality that memory can resemble.

Gerry: And then, "It Is a Beautiful Day (1000 Years Later)" has your most eccentric poetry and vision for a time in the future.

Leo: In places like Coalville, the end of the industrial economy ruined people's lives. There was little plan for what came next. The landscape was left ravaged, too. Gradually, the mines "reverted to nature," either deliberately through planned redevelopment or through neglect. So the open-cast site became the Sence Valley Park. It's now semi-wild woodland and a lake. "It Is a Beautiful Day" imagines a moment in the future where any trace of human activity might have disappeared, except for a few skeletal machine parts, there to be discovered by extraterrestrial explorers.

I haven't yet come to terms with whether this is an optimistic or pessimistic view of the future. It did seem right, however, that the album should end with a vision of 'absence,' since I myself am now absent from that place.

Gerry: Are there any plans for a performance, gig, or launch party? There certainly seems to be scope for this to soundtrack a video or short film.

Leo: Not yet—but maybe soon! I envisaged the album as a kind of 'radiophonic' piece—sounds and music for listening to alone, even for falling asleep to alone—but a live version isn't out of the question.

Gerry: Is it just coincidental that I mentioned Jonny Trunk at the start of the interview, and then I spot you're involved in Pulp's new album? Trunk is best mates with Martin Green and Jarvis Cocker. How did that collaboration come about? Funnily enough, I can imagine a Cocker version of Sleep in the Shadow of the Alternator, as he comes from Sheffield, the Woodhead Tunnel, heavy coal industry, freight trains—cover version or remix perhaps?

Leo: It was very nice indeed to be a tiny part of the new album! The Elysian Collective, who were responsible for the strings on More and on tour, asked me to come and join the twelve-person choir in the studio. I've occasionally done other things 'close to' Pulp, though: I played live with the band for a one-off concert about twenty years ago and worked with Jarvis in the studio when he produced my friend Serafina Steer's album The Moths Are Real, which is a thing of great beauty, by the way.

I love the use of speaking voices in music—something that's pretty obvious in my work, but was also the subject of my PhD thesis. I tend to think of my music as adjacent to the experimental work of American musicians such as Laurie Anderson and Robert Ashley. But you're quite right: Jarvis is an amazing exponent of spoken word, and I love those epic Pulp tracks where the narration gives the music a cinematic quality, like "I Spy" or "Sheffield: Sex City." It's entirely feasible that that part of my musical DNA subconsciously informs the strange things I'm making these days.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

Comments