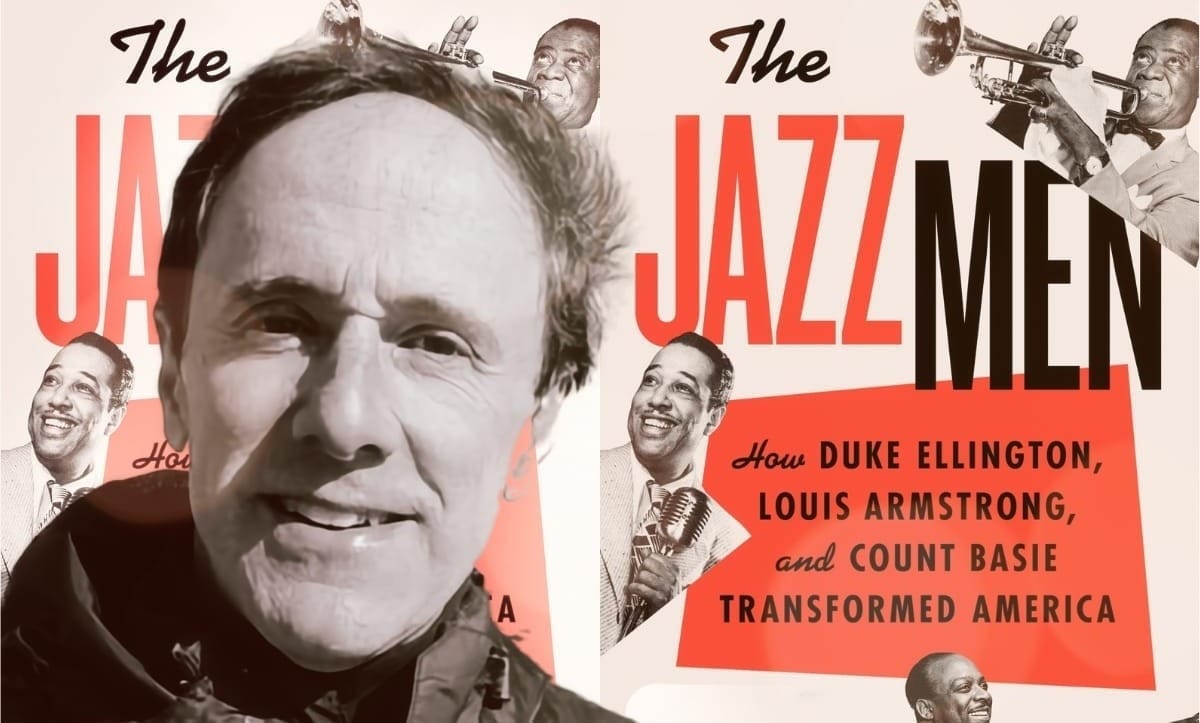

Larry Tye has spent his career uncovering the untold stories of last century’s American history. This New York Times bestselling author has written biographies of figures spanning from public relations pioneer Edward Bernays to Senator Joe McCarthy, and his latest work may be his most ambitious undertaking yet. The Jazzmen: How Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie Transformed America, published by HarperCollins, examines how three of America's most celebrated musicians became unlikely pioneers in the fight for civil rights.

Tye's previous books have consistently centered on what he calls "certain basic stories that matter in America." He explored the rise of the African American middle class through Pullman Porters in Rising from the Rails and chronicled the racial integration of baseball through pitcher Satchel Paige. His work on The Jazzmen continues this thread with a unique twist: Tye concentrates on these musicians' lives offstage and their incremental efforts to advance racial justice in mid-20th-century America, rather than their performances and recordings.

As is Tye’s practice, he conducted extensive research for the book. He interviewed over 200 people, among them jazz luminaries Wynton Marsalis and Jon Batiste, plus former President Bill Clinton. Tye gained access to previously unavailable archives and personal papers, allowing him to construct an account that goes beyond the familiar stories of musical genius to examine how Ellington, Armstrong, and Basie used their fame (and the relative safety of private Pullman railroad cars) to challenge Jim Crow segregation and white America's racial assumptions. His research uncovers how these three men, each in their own way, helped write what he calls "the soundtrack for the Civil Rights Revolution."

Host Lawrence Peryer recently hosted Larry Tye on the Spotlight On podcast. In their fascinating conversation, Tye discusses how a promise made to Pullman Porters led Tye to this project, the transformative moments that changed his understanding of these jazz legends, and why he believes their stories remain urgently relevant to contemporary America.

You can listen to the entire conversation in the Spotlight On podcast player below. The transcript has been edited for length, clarity, and flow.

Lawrence Peryer: There are two interrelated questions I have about The Jazzmen. What brought you to that project? And is it related to your work on the Pullman Porters and Satchel Paige? Are they all somehow intertwined?

Larry Tye: They are. About twenty years ago, I wrote a book about the Black men who worked on the railroads, known as the Pullman Porters. And when I talked to the Porters, they made me promise that when I got done writing about them, I would write two other books. One was on a sports figure that they carried on their trains, and that was the fireballing pitcher and racial pioneer named Satchel Paige.

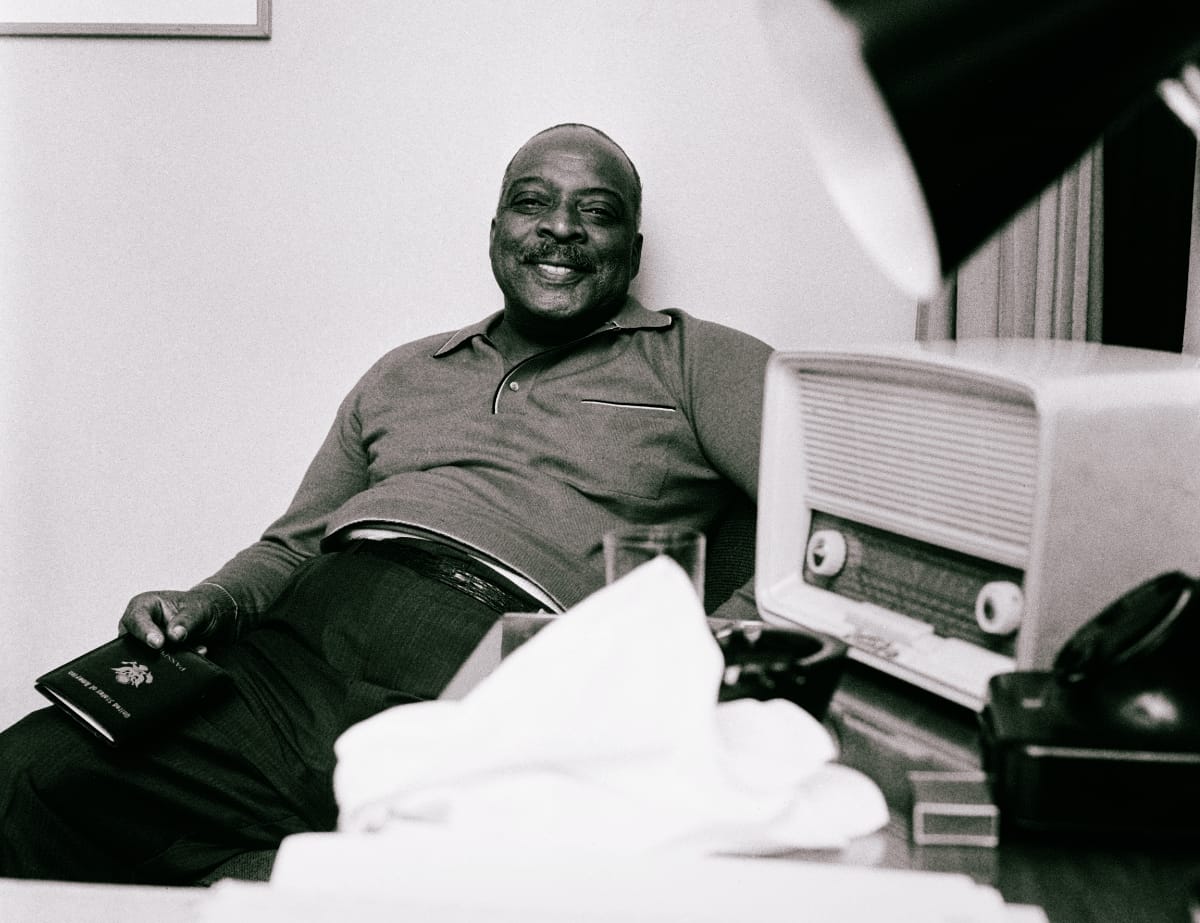

The other book was on their three favorite passengers, three guys named Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie. I think the reason the Porters loved these jazz men and the reason the jazz men, in turn, loved the Porters says a lot not just about them, but about America.

Even though Ellington, Armstrong, and Basie were three of the best-known Americans on the planet, when they traveled in the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s below the Mason-Dixon line, if they made the wrong choice on where they tried to get a meal or to stay for the night, that could be a fateful decision.

They could be berated, beaten, and even end up at the end of a lynching noose for the simple mistake of having the audacity to try to eat or to sleep in a whites-only facility. And so what they did was something I think is quite brilliant: when they could afford it and they could afford it for much of their careers, they would hire a private Pullman sleeping car to accompany them when they went south. If they were performing a concert, let's say in Atlanta, at the end of the night, they knew they had a plush bed waiting for them made up by the Pullman Porters. They had a delicious meal cooked by the dining staff of the Pullman car, and most importantly, they had the serenity of knowing that they would have a safe place to be.

In return for the staff on the Pullman car, they performed a private concert in the closed capsule of that railroad car in the middle of the night. And I don't know about you, but if I could go back to any moment in history, it would be for the Duke Ellington Orchestra to be playing all night just for me.

Lawrence: And that's after a long evening's worth of work. What a way to unwind! That's incredible. So tell me a little bit about that promise. You took up that mantle—you said yes.

Larry: I did, and I took up that mantle for a very simple reason, which I think that, sadly, race remains the story of America. We have never reached the post-racial universe we dreamed of, and thought that maybe with Barack Obama’s election, we were finally there. This was written for my kids and grandchildren. I have one grandchild who was born on the Fourth of July, and I hope that by the time he reaches an age where he’s conscious of these issues, race will be less of a problem.

But I think that, trying to take people back and tell them a story of the history of Jim Crow, we have to do that in a way that makes that story palatable. Take the story, for instance, of Satchel Paige. Satchel Paige was born in Alabama, the very year that the Jim Crow laws were passed there, and he was the one who set the table for Jackie Robinson.

So his life is a perfect look at the history of Jim Crow. Same with the Pullman Porters, and even more so, I would argue, with these three jazz guys. They were born in an era when Jim Crow laws were being passed, and they helped ensure that we would get beyond those Jim Crow laws by taking their extraordinary music to white America and convincing white Americans that the sky wouldn't fall if they were to hear Black geniuses playing the trumpet or the piano.

Lawrence: I've read elsewhere where you spoke honestly about not being a jazz scholar as you went into this work. Was there anything about your previous work that sort of prepared you for immersing yourself in this world of these three men?

Larry: I had some preparation, including understanding a little bit about race history in America and the Jim Crow laws. But I am pretty close to being tone deaf, and I might be the last person in America who ought to be sitting down and writing a book about jazz. On the other hand, I have been a journalist for my entire professional life, and journalists begin every day knowing very little about the story they're going to have to try to educate the public about at the end of that day. And what they do in between is talk to people who are smarter than they are, who educate them. And that is precisely what I did with this book.

I interviewed somewhere between two hundred and 250 people who were incredibly gracious and understanding of how little I knew. I interviewed people like Wynton Marsalis, the great trumpet player and jazz educator. Jon Batiste. I interviewed a guy who helped me understand the politics of jazz, named Bill Clinton. They were people who probably didn't care about me, but they cared that an author who was going to write a book for a substantial publisher on three people as important to them as Ellington, Armstrong, and Basie. They wanted to ensure that I got it right.

And so, you keep talking to people and read everything available, including old newspaper clippings, magazine stories, and the hundreds of books written on jazz and these three guys specifically. What I realized, the more research I did, was that while America didn't need me to tell them why Ellington, Armstrong, and Basie were musical geniuses, almost every book that had been written about them was written, understandably, about their life on the bandstand. I was trying to write about the opposite. I was trying to write about what these guys did when they weren't playing their instruments and performing in front of audiences, and how they moved the dial on the whole civil rights discussion in America. They wrote the soundtrack for the Civil Rights Revolution, and that was the story I was most interested in telling.

Lawrence: Your humility in how you talk about this strikes me as like this philosophical mindset I like to think about, which is the beginner's mind. You may be the least likely person to write a book about these jazz figures, but I like to think of people in your position as being ideally suited because you can come in with a beginner's mind and ask questions that the experts might not ask. I bet it's an advantage to come in without being overly immersed in the subject, but I imagine it's also daunting.

Larry: It is both, but that is a perfect way of saying it. It is a beginner's mind. That is what a journalist does in every story they write. That's what I do in every book I write. I try to write it so that people with no background aren't intimidated by getting into the topic. If you do that well enough, and if you've done your research well enough, you're also writing for the experts. If you write just for the experts, you'll lose the beginners. But if you write for the beginners and you have something new as well as a simple story to tell, then you will bring in the experts.

I mentioned that I talked to people like Wynton Marsalis, Jon Batiste, and Bill Clinton. They thought they knew these three jazz men intimately because they knew them musically. But I’m convinced, after the fact, that I told them something they didn’t know, based on the reactions I got. They didn't know what these guys had done—what they did just about every day of their lives to, in some incremental way, make the world a little more just, and to make Blacks a little more able to participate in the full range of life in America.

Lawrence: Maybe this is at the risk of being metaphysical, but how do you know when you've gotten to the point where you can tell someone's story? You come in sort of cold, and now you've got the authority to speak on them. Do you have a barometer for that?

Larry: I do. And my barometer is when I start reading and hearing the same kinds of stories for the second or third or tenth time, and then I realize that you could go on researching forever. And a lot of academics do go on researching forever. I've got deadlines, and we live in a real world. So, we know we have a time limit on the research part of our work, and it’s not just about time. It is hearing enough of something that you feel you can tell it with authority.

As a journalist, I spent a lot of my time as a health reporter. I’ve found that the smartest doctors and scientists I’ve spoken to are those who can explain complex concepts in the simplest terms. They know all the nuances, but they also know how to express their expertise in plain English. The more people fall back on jargon or on supposedly expert testimony, the less they really understand that everything boils down to relative simplicities.

I just want to say one more thing that, without getting overly political, I think the stories that we've been talking about, whether it's the Pullman Porters or Satchel Paige, or Ellington, Armstrong, and Basie, are more important to be telling at this political moment than any time maybe during my lifetime. It's a moment when we're being told that the story of racial injustice is somehow besmirching this notion of what America stands for. And I think what America stands for is its history with all of its ups and downs and its sense that we are hopefully going to make progress, but the only way to make progress and the only way to have a more racially just society is to face up to the truth about our history, not some rose-colored glasses view of what we wish our history had been.

Lawrence: I don't know how to probe that with you without devoting the rest of our time together to that, except to say yes, of course. I mean, there's plenty of both shame and grandeur to go around in this country's history, and I think it's a much lesser experience to not fully explore both. To brush all the mistakes aside is dangerous at best.

Larry: It is, and it's brushed aside often in the name of sort of optimism and 'let's look at the positive.' Well, I think the most optimistic stories out there are the kinds of stories we're talking about now. Men like Ellington, Armstrong, and Basie, who grew up in a world where they were told, "This is the water fountain that you, as a Black, can use, and this is the one that is limited to whites. This is the better school that you can't go to, and this is the one that we're going to let you go to." The idea that these three guys could come out as optimistic as they were, to me, is an ultimate affirmation that people can be optimistic because they work hard to make things better, and that's the way to be an optimist, not to deny the truth of our history.

Lawrence: In the course of what I think of as the forensic detective work you've done, I’m curious about moments where you spoke with someone who laid something on you that maybe changed your understanding of one of these men.

Larry: A transformative moment for me that is emblematic of lots of moments involves Louis Armstrong. This guy I grew up seeing on television went through, in the course of a performance, a dozen handkerchiefs, and he did a lot of hamming it up in front of the TV camera. He was often called an Uncle Tom for that. I thought he was a great trumpet player and had a great voice, but when it came to racial issues that he was a little bit backward, and to a lot of young Blacks and whites of his era, he was a bit of an embarrassment.

The ‘aha moment’ for me came when I understood what had happened to Louis Armstrong back in the year 1957. The signature civil rights issue in America that year was the attempt by a federal judge's order to integrate the all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. The governor of Arkansas at that moment was named Orval Faubus, and he said, essentially, "These kids will integrate this all-white high school over my dead body.” Our war hero President Dwight Eisenhower said, "This is a state matter, I'm going to stay out of it."

An enterprising young journalist knocked on Louis Armstrong's hotel door and said to him, "Mr. Armstrong, I wonder what you think about what's going on in Little Rock." Louis Armstrong had had it with being accused of being an Uncle Tom. He decided to sit this reporter down and tell him what he truly thought. He called Governor Faubus a word that I won’t use in the polite company of your readers, but it began with M and it ended with R. It got translated in family newspapers into "an uneducated plowboy." He called our war hero President "a gutless so-and-so," and he basically let the governor and the president have it.

Of course, the next day in newspapers around the world, the guy they were previously accusing of being an Uncle Tom, they were now accusing of being an unpatriotic American. They said he had gone too far. But there was one guy who listened to what Louis Armstrong said, and that was the guy sitting in the White House named Dwight Eisenhower.

And I can't prove to you, Lawrence, the cause and effect, but I believe it with every ounce of my intelligence and empathy. I believe Dwight Eisenhower sent in federal troops to protect the kids who became known as The Little Rock Nine because he had been called out by the great Louis Armstrong, who he adored, and Eisenhower understood that Armstrong was right.

Those are the kinds of moments that I had where I started seeing somebody that I had seen in a certain way, in an entirely different way. And those are the moments where you learn, research, and want to write a book. You're learning something yourself, and if you don't have those moments and you don't change your mind about people, then you're not doing very good research.

Lawrence: I loved that part of the book, not least of which was because the story of the young journalist—I mean, the whole thing was so improbable. If it were fiction, it would've been such a compelling little narrative.

Larry: The young journalist, who was essentially a student journalist at the time, the editor of the serious newspaper for which he was interning, didn't believe that this was for real. He had the journalist go back to Louis Armstrong, who signed a statement essentially attesting that “this is what he said, and this is what he was comfortable going into the newspaper,” which changed the journalist's life. As I say, it changed my understanding of who Louis Armstrong was, and that of many other people. There were comparable moments with Count Basie and with Duke Ellington, where I stopped seeing them as just great musicians, and I started seeing them as great civil rights pioneers.

Lawrence: Let's talk about Count Basie for a moment. Something I enjoyed about the book was the way you leveled the playing field on his behalf. We all know he's great, but I think there's a tiering in some people's minds amongst those artists, or certainly, he's not as well known in all quarters as the other two. Is there something you discovered about him that convinced you that he matters as much as the other two?

Larry: When we contemplate there being a Mount Rushmore of jazz musicians, nobody in their right mind would ever question, as you're suggesting, that Ellington and Armstrong belonged there. They were just the instinctive choices. Count Basie was intriguing to me because it was more than just his piano playing or songwriting; I think he was the premier band leader. Louis Armstrong was essentially a soloist who had accompaniment at times. Duke Ellington was known for his composition, his arrangement, and, to some extent, his piano playing.

It was Count Basie who could bring together some of the greatest instrumentalists and vocalists of the era. And he had a modest personality that allowed him to be in the background, knowing how to bring out the strengths of the people playing with him. He didn't need to be center stage and under the spotlight, and so it was Ellington, the composer and arranger. It was the instrumentalist Louis Armstrong, and what I think was the best band leader ever, Count Basie. And they used to say about Count Basie in his era, that if you were listening to the Count Basie band and your toes weren't tapping, you ought to go see a doctor the next day because something had to be anatomically wrong with you.

Lawrence: Tell me about the obvious choice you made around balancing the impact these men made, the longevity of their careers, with sort of being very honest and not hiding their flaws.

Larry: So I've written about people who start as my heroes, whether it was Bobby Kennedy or Superman or Satchel Paige, and if I can't find some flaws in them, some weaknesses, they're not real flesh and blood characters. I've written about people I initially despised or seriously questioned, such as Joe McCarthy. And if I can't find something good to say about Senator Joe McCarthy, then I'm missing the point on why half of America came to love Joe McCarthy. And with these three guys, most of what I say in the book is a celebration of them. The fact is, they had weaknesses. They were God-fearing men who prayed before every meal and believed in much of what was good in the world. However, they regularly violated at least five of the Ten Commandments, with the most frequent transgression being the one about being faithful to one’s spouse.

They just didn't know how to be faithful. They tried hard, and they ended up with wives or companions who understood this weakness in them. But it was a weakness. So, you've got to keep looking until you find things that defy our initial sense of who somebody is.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments