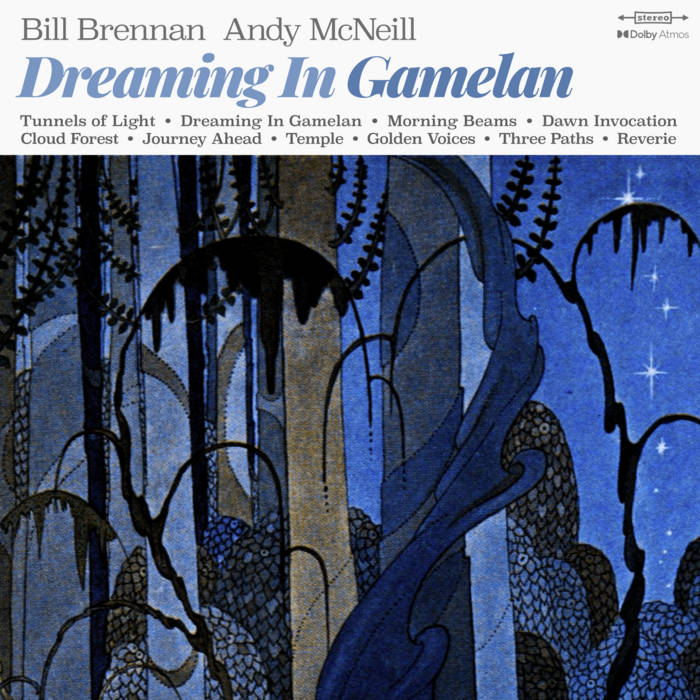

Bill Brennan and Andy McNeill recorded Dreaming in Gamelan over twenty-five years, though for most of that time the recordings sat untouched. The initial sessions took place in 2001, with Brennan borrowing bronze gamelan instruments from Evergreen Club Contemporary Gamelan, while McNeill handled the recording. The project moved in fits and starts: a chamber performance at Massey Hall with Evergreen Club, then years of silence. Finally, the two composers shaped it into the album we discuss here.

This music does not sound like typical gamelan, even though it uses traditional Sundanese instruments made by Javanese craftsman Tentrem Sarwanto. McNeill added electronic treatments. Electric violinist Hugh Marsh contributed parts that sometimes play a role similar to the traditional rebab and other times create textures unrelated to Indonesian music. Nine shorter tracks explore different combinations before a ten-minute closer lets everything dissolve. Finally, Ron Searles mixed the album in the Dolby Atmos immersive format.

Bill Brennan has appeared on 140 albums, won the 2023 MusicNL Classical Album of the Year, served as musical director for CBC's Vinyl Café, and studied gamelan with Sundanese master Ade Suparman in Indonesia. Andy McNeill composes for television and film (PBS documentaries, the cartoon series Agent Binky: Pets of the Universe) and records ambient music as Maple Mountain Sunburst. Their Dreaming in Gamelan is twenty-first-century music, benefiting from Brennan's knowledge of West Javanese traditions and McNeill's attraction to what he hears as gamelan's strangeness.

In this conversation, we discuss the unusual genesis of Dreaming in Gamelan, the process of working with hand-forged instruments from Surakarta, the ethics of crossing cultural and genre lines, and the technical process of transforming fifty-second documentary cues into expanded compositions mixed in Dolby Atmos.

Lawrence Peryer: Dreaming in Gamelan has quite an origin story, beginning as a CBC documentary score in 2001, evolving into a live performance at Massey Hall in Toronto, and now becoming this release almost twenty-five years later. Bill, when you and Andy first set up those hand-forged instruments in your living room with a portable recording setup, what was that week like? What did you sense you were creating together?

Bill Brennan: It was very cool. First of all, I hadn't done any recording where I was co-engineer, co-producer, and performer. So that was very exciting, and having the instruments set up in my house, where the recording schedule was a bit more relaxed than in a rented studio, offered a certain sense of freedom. It allowed for a creative space where we could compose as well as improvise. We also had a TV monitor set up so that we could record while looking at the documentary video. That's certainly not unusual for a composer to have access to the documentary video, but for me, it was very interesting to try out different musical material while watching the video to assess what the right tone should be for various cues.

In terms of what I sensed that we were creating together—obviously, we were creating a score for the documentary, but I think we saw the cues as musical vignettes. With that in mind, we always had a sense that we could expand on the material we recorded for a future project, including a concert suite and a recording.

Lawrence: Andy, what drew you to accept that initial CBC project as a collaboration rather than a solo venture? You mention discovering considerable overlap in your musical interests despite markedly different backgrounds.

Andy McNeill: I had been scoring documentaries for the CBC on my own, so the idea of working with another composer was new and interesting. The opportunity to collaborate with a musician of Bill's level was an absolute no-brainer. And we were already friends, so I knew it would be a lot of fun.

As for shared musical interests, I'm pretty sure we connected over stuff like ECM, Harold Budd, Brian Eno, Bill Frisell, Duke Ellington, and Steve Reich. I remember there was also this amazing Brazilian percussion group that I'd been getting into, Uakti. And then I found out Bill was actually good friends with them.

Lawrence: Bill, how did your path lead to such an intensive study of gamelan traditions, and what was it like learning this music within its cultural context?

Bill: That's a good question, because it really points to important mentors that I have had in my life. When I was quite young, I was fortunate to study with Don Wherry, a fantastic percussionist who moved to my hometown of St. John's in the early 1970s. I studied with him for many years, and he exposed me to the music of Steve Reich, contemporary jazz artists like Cecil Taylor, and the music of Igor Stravinsky, as well as the percussion repertoire of composers like Carlos Chávez. In the 1980s, he started the internationally renowned Sound Symposium, and I had the opportunity to perform with folks like Freddie Stone, Rivka Golani, and to have some of my percussion compositions premiered.

While at the University of Toronto, I studied with Russell Hartenberger. Russell is a founding member of the percussion ensemble NEXUS and played in the Steve Reich Ensemble for years. Russell taught the African Drumming Ensemble; as students, each week we gathered together and learned about Ghanaian drum patterns. He also had a tremendous vocabulary in the music of other cultures. The artistic director of the Evergreen Club Contemporary Gamelan, Jon Siddall, often asked Russell for advice about players to have in his ensemble. In 1984, Jon reached out to me, as Russell suggested I would be a good group member. And that is when I first saw West Javanese instruments. Jon had studied Gamelan Degung in California and had a lot of knowledge to share. Of course, over the years, the Evergreen Club brought many master musicians from Indonesia to Toronto to work with the ensemble. To work with these masters was incredible for so many reasons.

Lawrence: Andy, you describe being "wide-eyed" about gamelan music. What specifically about these sounds and structures captivated you?

Andy: I love the clear bell-like tonalities, the deep sustaining gongs, and, of course, the unusual tunings. It's hard to describe, but I'd say there's a feeling of suspension, a kind of emotional ambiguity in this music. It's a completely refreshing sound to these ears. And then there's the interlocking patterns, the pulsing repetition. I love that kind of thing.

Lawrence: I love this quote from Andy: "There are all kinds of strange and beautiful in this music. It's otherworldly and completely transportive." Bill, how do you balance honoring the traditional gamelan degung forms while allowing for this sense of otherworldliness that Andy describes?

Bill: When one spends the time listening to gamelan degung music and learning from master artists, getting to know aspects of the culture and the people themselves, the fascination is always there, and the respect continues to grow. Years ago, I was fortunate to study in Bandung, West Java, for a month with Ade Suparman. Ade is a composer himself. It’s really interesting to see how he appreciates the tradition in his original music. Honoring the tradition is partly in how the instruments are played, how they are treated, and in finding the emotions that are connected to the music tradition. In the meantime, I wouldn't say that our music in any way connects to a creative interpretation of gamelan degung music, but it connects to the feelings and sensitivities that I think traditional gamelan music conveys.

Andy: I like to think of it as the gamelan as heard from within a dream. Hence Dreaming in Gamelan.

Lawrence: The album embraces what you call "ambient music, jazz, and experimental approaches" alongside West Javanese traditions. Andy, what are your thoughts on genre boundaries when working with music that has such deep cultural significance?

Andy: I'm not sure we really thought about genre boundaries, to be honest. For me, it was an exciting new sound palette, one that I was very fortunate to have access to. Having said that, the reverence and respect for the West Javanese gamelan tradition were always there, and there are moments with a nod to traditional performance technique and even composition. We didn't put up too many rules or parameters, and we weren't afraid to step outside the boundaries to make the new pieces work for us.

I do remember talking about tuning. There were times we might've made adjustments to match the gamelan instruments and vice versa. Other times, it was better to leave any intonation rubs in. And obviously, things like overdubbing vibraphone, adding bass, percussion, and the weird processing go way outside the tradition.

Lawrence: Bill, what's your perspective on those same boundaries? How do you navigate between your deep traditional training and this more experimental context?

Bill: I grew up playing percussion instruments and then continued my studies in percussion at university. I have made my living from playing percussion instruments for over forty years. So much of what we learn as percussionists is informed by cultures from around the world. Many of the mallet instruments we play have roots in Guatemala and West Africa, cymbals in Turkey, drums in many cultures, tuned gongs from Asia, and so on. So it's natural for percussionists to be interested in music from around the world. And we think about sound as performers. We might use a certain set of cymbals for a Mahler symphony, but a different set for Ravel. We may tune our snare drum differently depending on the size of the ensemble. Sound is important and personal.

As experimenters and composers of sound, we can't help but be influenced by what we hear. Music is very seductive in that sense. I love music from Brazil—the rhythms, the feels. And it has seeped into my music; the music I write for percussion is tremendously influenced by the rhythms of Brazil and West Africa. I think one navigates by appreciating and honoring the boundaries and by listening inside for honesty in creativity.

Lawrence: You recorded the initial sessions using Tentrem Sarwanto's hand-forged instruments from Surakarta, which are sought after by gamelan ensembles worldwide. Bill, what was it like working with these particular instruments?

Bill: It's hard to describe their richness in sound, but the sonorities are very complex. On each instrument, aside from the pitch, each note has a unique, slightly different quality. These qualities can affect the way you play, the way you improvise, and the way you compose. For example, some instruments ring for a very long time, such as the large gongs, and thus one might use them at structural points in a piece to enhance cadences. So in many ways, they help you create your vision.

Lawrence: Andy, what was your experience with those instruments as someone coming to gamelan from outside the tradition?

Andy: These instruments are visually beautiful, handcrafted bronze objects. At first, I might've been a little intimidated. But with naivety comes fearlessness, I suppose, and with some guidance from Bill, I was able to pick up some of the basic techniques reasonably quickly. It really was a fascinating process. But it's safe to say a good number of parts in those original sessions would have been performed by Bill, the true percussionist in the duo. It's also worth remembering that at the time, we were scoring a film to a deadline, often live to picture. So things had to come together quickly.

Lawrence: Ron Searles's Dolby Atmos mix seems particularly important to this album. How does that immersive audio experience relate to the traditional spatial aspects of gamelan performance, where musicians and audience exist in a particular acoustic relationship?

Andy: The original session was recorded with a pair of AKG 414 mics through a Tube-Tech preamp into an Akai DR16 digital recorder. Some performances would have been close-miked, others with a stereo pair of overheads in the room. Years later, when it was time to revisit the tracks, we were working with both the original stereo mixes and some individual WAV files that I'd fortunately transferred. There was definitely some archaeology in retrieving those session files.

We approached the Atmos mix not as a representation of any acoustic performance space but rather as a completely artificial immersive listening experience. But not so things are flying around your head in a gimmicky, distracting way. It's easy to get carried away with that in Atmos—like in the early days of stereo. I think Ron does a fantastic job at balancing that. Hearing it in an actual Atmos space, with all the speakers around and above you, including the subwoofers, is really special. But it also sounds pretty fine on AirPods or a good pair of headphones.

I did my own stereo reference mix in my studio, and then every individual track was bounced and sent to Ron. From that point, he had creative freedom to place things as 'objects' in the spatial field. Ambiences and effects were usually baked in, but if it made sense, I'd bounce that stuff as a separate element.

Speaking of which, the Atmos versions can be heard on Apple Music, Tidal, and Amazon. And the full hi-res Atmos version of the album will be available for download at immersiveaudioalbum.com.

Lawrence: Can you describe your process for augmenting the original 2001 recordings both compositionally and with processing? How do you maintain the integrity of those sessions while developing the material?

Andy: I spent time parsing out individual fragments and stems from the recordings and then processing them through a handful of software plugins and outboard gear. There was a fair amount of experimentation, and not everything worked, of course. I'm a big fan of the software Cycles from Slate + Ash. It's an amazing tool for helping create textural material out of anything. Rhythmic stuff too. I also use a pedal called Ribbons from Kinotone Audio that emulates an old tape machine. It's fantastic. You can slow things down, reverse them, and create loops that degrade over time, all in stereo.

We also did some sampling sessions later on, and we were able to construct really detailed multilayered Kontakt instruments for some of the gamelan instruments like the bonang, jengglong, and panerus. These ended up being invaluable for extending and augmenting the pieces. What might've been originally a fifty-second cue for the documentary could eventually develop into a three-minute piece.

Lawrence: Bill, what was your role in that expansion process? How do you hear the relationship between those original recordings and what they became?

Bill: In this process, I let my composer ears guide my thoughts. Sometimes I wanted to hear certain sections repeated or felt the need to add some piano to make the music go to a different place or space. Andy's knowledge of processing and his creative exploration of the compositional world through this medium are fascinating to me. His compositional sense I truly respect. We communicate well and have a similar sense of play, I think. And with that in mind, I feel the final realized pieces have a more contemporary sound, with more color. I also feel the music has found a home that is closer to us as people. It's a little more personal.

Lawrence: Andy, can you walk us through how you constructed the ten-minute closing track "Reverie" and how it relates to the shorter, more vignette-like tracks that precede it?

Andy: That piece is made up entirely of fragments from the rest of the album, processed and blurred to the point they are barely recognizable. I did a lot of experimenting with layering and weaving them together. At first, the idea was to have these shorter 'ambient' pieces scattered among the other tracks. But we agreed it worked much better to close the album with one longer piece. It's definitely one for eyes-closed, deep submersion.

Bill: I think what Andy has created is stunning. I feel "Reverie" is like a kind of journey through our entire process of creating this music.

Lawrence: Looking at this project now as a completed work, Andy, how do you see it fitting into your broader artistic practice? What does it represent in terms of your development as a composer?

Andy: Improvising with another musician in a space and then capturing the recordings as compositional material, like sonic fodder, is really interesting to me, and I can't wait to do more of it in the future. So yeah, the collaborative part of this has been really great. Just to be able to bounce ideas off another person and not have to make every decision yourself! And working with Bill is an absolute joy. We have a lot of fun.

I really like this as a companion to my Maple Mountain Sunburst stuff. It's different, though some overlap in the use of layered patterns, cycling, and rhythmic elements. And they're both really kind of trippy.

Lawrence: Bill, what does this project mean to you in the context of your four decades of musical work? Where does it sit in your artistic story?

Bill: It is a pretty unique project for me. I mostly compose music for percussion and piano and co-write with my friend Andrea Koziol, who is an amazing composer and lyricist. I really like the music that we wrote, and I really enjoy working with Andy. Like Andy said, we have a lot of fun creating together. I am quite proud of the album. So it sits pretty high in my artistic story.

Lawrence: What do you hope listeners who are unfamiliar with gamelan music will take from Dreaming in Gamelan? And what do you hope it offers to those already familiar with these traditions?

Andy: I like to think of it as a forty-minute journey through some kind of exotic, surreal world. I hope it offers an unusual, novel musical experience. Hopefully, it's accessible enough for open-eared listeners unfamiliar with gamelan music but with new ideas that will appeal to those familiar with the gamelan tradition.

Bill: I hope listeners can get lost in the sounds of the record. I think it offers some interesting sonic worlds—it's groovy at times, it's spacey at times, it's melodic. But I hope people get to experience the beautiful instruments that are at the core of the record. And for those who are familiar with gamelan degung, I hope that they enjoy our music and our playing.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments