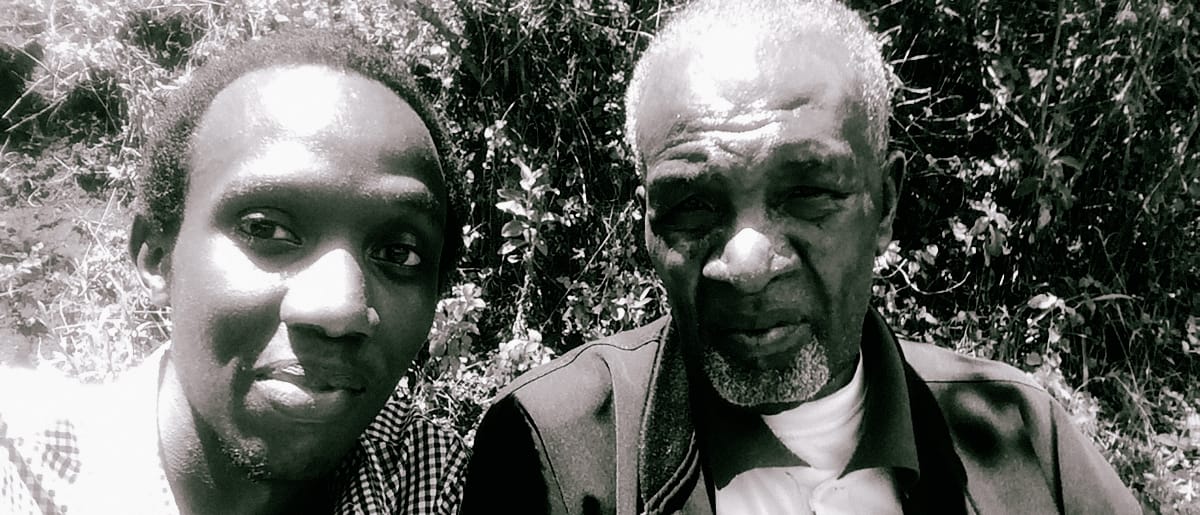

To prepare the retrospective collection Heavy Combination (1966–2007), cassettes were lovingly wound back and digitized by Joseph Kamaru's grandson, likewise named Joseph, and also known as the renowned ambient sound artist KMRU. For this release, the full sonic language of Joseph Kamaru's genre-expansive music finds new air in the years following his passing in 2018.

Traversing the landscape of Kenyan highlife guitar riffs to the deep, resonant beat of the drum machine and keyboard-first disco grooves, Kamaru's music captures the full scope of his musical career. The legacy of afro-funk chimes with the pulse of his incisive folk-style laments, with this latest release shining a bright light on seventeen tracks lifted from five decades of Joseph Kamaru's legacy as the "King of Kikuyu Benga," a long-revered, admired, and treasured musician, political activist, and national icon of Kenya.

KMRU's documentation of his grandfather's prolific output reached far beyond the continent of Africa, with one familial foot planted in the electronic artist's current place of residence in Berlin, and another curious limb settled further afield in the UK. Piquing the interest of Disciples, a contemporary curator of underground sounds based in London, KMRU's archival process resonated with their pursuit of "lost" recordings and the unearthing of left-field sounds, with their catalogue spanning the restoration of degraded DIY tapes, self-ascribed "rephlexian braindance bangers," and the translation of teenage home recordings into steady and streamable digitized tracks. This dedication to casting the proverbial net out into the cosmic sonic aether is, arguably, God's work, whose success can be attributed to much of the honest, committed musical curiosity I admire so wholeheartedly.

This curiosity about overlooked scenes and sounds is not dissimilar to my interest in musical icons whose fame dissipates outside of their locale. Kamaru's influence in the Kenyan music scene was sincere, yet his impact is little known outside East Africa. Born in 1939 in Kangema, Murang'a District, Kamaru left his homeland in the 1950s for Nairobi, where he sold fruit on the streets and later worked as a house help and nanny. Having eventually saved sufficient funds to purchase his first guitar, Kamaru went on to teach himself the accordion and keyboard alongside the wandindi, a one-stringed fiddle, and the cymbal-like karing'aring'a, effortlessly weaving both into his music. His earliest hits, "Celina" and "Thina wa Kamaru," were made for the dancefloor, laying solid foundations for Kamaru to become one of the most well-known Kenya Benga and gospel musicians, singing in his mother tongue, Kikuyu. Estimated to have sold roughly half a million records over his lifetime, Kamaru was revered as a musical multihyphenate of remarkable talent and resolve, living out his staunch political principles as an activist and national icon concerned with the social matters that reached through the everyday of Kenya.

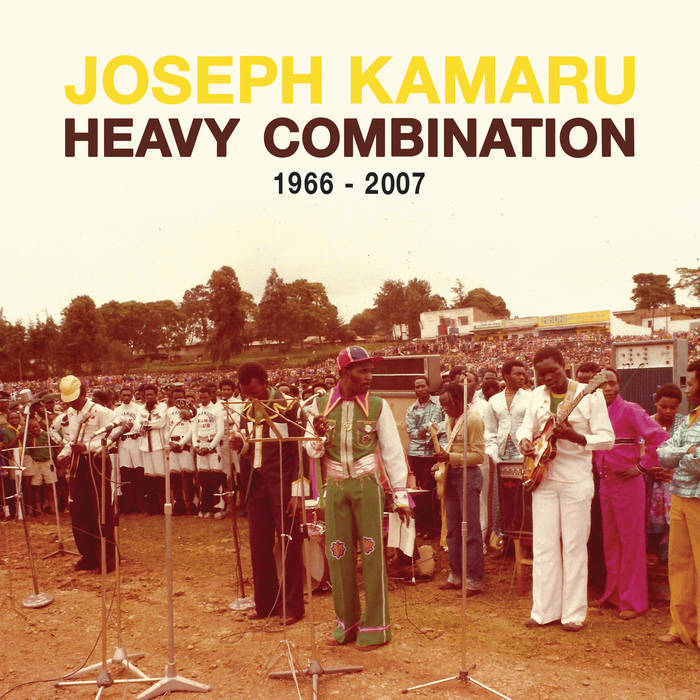

Remastered by Dubplates & Mastering in Berlin from KMRU's original tape transfers, the seventeen tracks of Heavy Combination (1966–2007) are housed in a record sleeve as designed by Karolina Kolodziej, depicting a lively visual of archival material from the Kamaru family vaults that underlines the importance of lineage and legacy in this release. Further underscored by extensive liner notes including essays contributed by Kenyan academic Maina wa Mũtonya, music journalist Megan Iacobini de Fazio, and KMRU himself, the ambition is clear and lucid—Kamaru will be heard far and wide for many years to come.

As Megan Iacobini de Fazio details, Kamaru was among the first Kikuyu musicians to champion benga, a guitar-led musical style pulling from the roots of Congolese rumba and West African highlife. Forging a resplendent sound that combines traditional storytelling with the excellently articulated "propulsive grooves" incidental to Kamaru's genre, de Fazio shares the socio-political context that richly informed his prolific musical output. Helping to define the moral and political consciousness of post-independence Kenya, Kamaru bore witness to untold brutality and coloniality at the hands of British forces, shaping, in de Fazio's words, why he would continue to write songs for the rest of his life.

Hailed by Voice of Kenya radio presenter Job Isaac Mwamto as "Kenya's Jim Reeves," Kamaru was a steady constant in the East African music scene and political sphere, recording nearly two thousand songs, sparring with moral obligations, and offering life teachings throughout his career. Despite his dependable presence across Kenyan airwaves, Kamaru's career wasn't without flux; in the 1990s, he announced he was "born again," proclaiming that he would no longer perform the secular music that had originally built his career.

Whilst this shift marked a marginal loss in record sales, Kamaru was a firm fixture in the physicality of the Kenyan music scene, eventually opening City Sounds (later Kamaru's City Sounds) on the iconic River Road. With a studio upstairs and a music shop on the ground floor, City Sounds became a mainstay for musicians countrywide—a coveted destination for musical exchange, creation, and production. This naturally extended into the establishment of a number of other music stores and labels founded by Kamaru, but City Sounds remained a vital and formative catalyst for the development of a new Kenyan sound.

A physical manifestation of Kamaru's musical and cultural impact isn't just limited to shops and stores—before his passing, Kamaru expressed a strong desire to build a Kikuyu cultural home on one of his farms in Murang'a to protect the world that nourished him. This wasn't achieved in his lifetime, but the legacy he left is long admired and, in KMRU's own words, "continues to speak as [we] listen."

Graced with the same name as his late grandfather, musician and sound artist Joseph Kamaru, known on stage as KMRU, returned to Kamaru's work in its raw form, manually digitizing the family archive of tapes, CDs, and seven-inch records into forty-eight reissues now found on Bandcamp. Penning an essay titled "In Sound and Memory," found tucked into the record liner notes, KMRU shares the fruits of research-by-anecdote, hearing the tangential, yet resonant tales and memories of Kamaru that unearth the more quotidian of his connection to his community of fans, friends, and strangers. "Unreleased track versions were sent through WeTransfer links, midnight encounters in Lamu with a journalist who had interviewed him in the 1980s, a radio conversation in Berlin with a chef who shared a journal entry about meeting him, and a friend's mother who remembered attending one of his concerts in Nyeri," KMRU shares. "These and more stories kept unfolding through the reissue process," building something much larger than anything he initially anticipated.

I recently exchanged emails with KMRU himself, tracing how the slow work of listening and digitizing his grandfather's music has shaped his own understanding of what it means to take care of a name.

Elsa Monteith: You've written that your grandfather told you to "take care of the name Kamaru." When you first started digitizing those tapes in your childhood bedroom, what did "taking care of his name" mean to you, and what does it mean now, with Heavy Combination out in the world?

KMRU: There's both a weight and a beauty in carrying a name, especially carrying the name Kamaru. Over time, it has become more deeply imprinted on me, connecting with my practice and my life. I feel like I'm reliving a life that runs parallel to my grandfather's, or at least closely echoes it. For me, taking care of the name doesn't mean controlling it; it means letting the name be.

Elsa: Revisiting his catalogue became a weekly ritual for you—listening, converting, and uploading every Wednesday. How did that slow, repetitive work change your understanding of who Joseph Kamaru was, beyond the family member you grew up with?

KMRU: Listening to his music over the years has revealed stories from his life that I could only access through the music itself. It feels like a diary he left behind that I can return to in order to understand the life of someone whose name I carry. Through his music, I've grown closer to him, and it has become a profound source of inspiration in my own artistic practice.

Elsa: Kamaru's songs sit at the crossroads of so many things: Kikuyu language and proverb, benga, mwomboko, political commentary, moral storytelling. When you listen as a sound artist, what do you hear first—the politics, the poetry, or the sonics?

KMRU: Interesting question. I am mostly drawn to hearing the lyrics in my mother tongue; there's always an attention to the words. But the more I listen, the more layers unfold. His music is incredibly textural, shaped by varied instrumentation and the recording techniques available during his time, and I'm always curious about the nuances of his styles from his records. Each of his albums is so specific, revealing itself gradually and often rewarding after repeated listenings.

Elsa: Some of the songs on Heavy Combination feel uncannily present—"Kĩmiiri," for example, reads like a diagnosis of today's Kenya. How have recent events in Kenya shaped the way you hear his political songs now?

KMRU: His political commentary feels strikingly relevant, as if he had foreshadowed the Kenya we are living in now. I see his music as a point of departure for understanding the poetics of the country's politics. How power, struggle, and everyday life are articulated through sound and language. It's music that asks for reiterated listening; each return reveals something new.

Elsa: Your grandfather helped build labels, studios, and an extensive catalogue of incredible music. How do you think about that side of his legacy: spaces, economies, and the ecosystems that carried his work?

KMRU: I see this reflected in his autonomous way of working, how he released music, collaborated, and built his own ways around the music. That independence was essential in his time. Having the freedom to run a record label, a music store, and to oversee a pressing plant in Kenya created the conditions for Kikuyu Benga music to grow, circulate, and sustain an entire ecosystem. It wasn't just artistic freedom; it was economic and cultural agency.

Elsa: So much of his music is about people in motion—migration, long-distance love, rural-urban tension, social change. Do you recognize echoes of your own movement and displacement in the way he wrote about those journeys?

KMRU: More than ever in my life now, as I'm constantly in motion and navigating so many overlapping paths in my life and music. It feels deeply relatable. The music has become a place to go to when I need grounding, a familial sense-making of life.

Elsa: There's a strong sense in your writing that working on this archive has been a conversation between generations. Was there a particular song or moment in the process where you felt like you were finally "meeting" him as an artist, not just as your grandfather?

KMRU: Possibly "Njohi Ndirĩ Mwarimu." I transcribed this song for electronic instruments while studying for my bachelor's degree in Kenya. Studying and dancing his folk songs, which are included in Kenya's music curriculum, made me realize that this wasn't just family history but shared cultural knowledge. That realization became an awakening for me, and it pushed me to build a more personal, ongoing relationship with his music.

Elsa: You've spoken about the dream of a dedicated space in Kenya where people can sit with his work. What would your ideal home for the Joseph Kamaru archive look and feel like, and what do you hope younger listeners there and elsewhere might find in it?

KMRU: A living, lifelong installation where his work can be experienced, studied, and interpreted beyond purely academic contexts, remaining active and relevant for future generations.

Elsa: What kind of story did you want Heavy Combination to tell about Joseph Kamaru to someone hearing him for the very first time?

KMRU: A single brushstroke of what Joseph Kamaru's music is like.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmElsa Monteith

The TonearmElsa Monteith

The TonearmMiguel Angel Bustamante

The TonearmMiguel Angel Bustamante

Comments