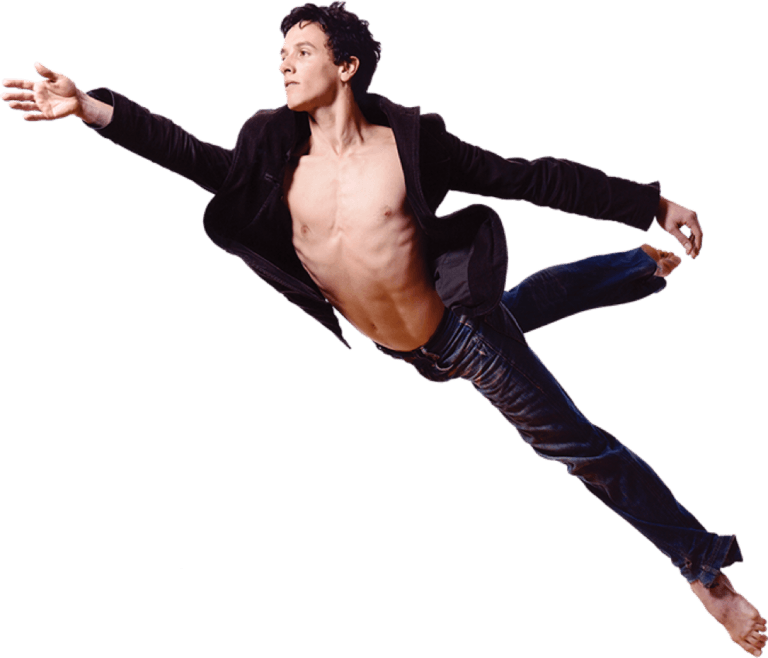

Adam Weinert is a Juilliard-trained dancer turned executive director of a major regional arts organization, Hudson Hall, in upstate New York. The forty-one-year-old choreographer, who has performed at venues ranging from the Metropolitan Opera to Tate Modern, recently stepped into the leadership role at the historic opera house that anchors the cultural life of this Hudson River Valley city. His appointment marks a homecoming of sorts, as Weinert first worked at Hudson Hall as an artist-in-residence over a decade ago, developing a dance piece about American modern dance pioneer Ted Shawn in what was then an unrestored space with a single working electrical outlet.

Weinert's résumé shows unusual breadth: he has reconstructed lost choreography using agricultural labor as research, founded a working farm at Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival, and chaired the Hudson Arts Coalition. His scholarly work on dance history has appeared in The New York Times and academic journals, while his performance career has taken him across four continents. The transition from performer to administrator represents a deliberate choice to root his practice in place, specifically in the small city he moved to eleven years ago with his opera director husband.

Hudson Hall is a physical manifestation of the tensions between local and cosmopolitan. Built in 1855 as the city's town hall, courthouse, and jail, the building now hosts events ranging from performances by internationally acclaimed artists to community workshops. Under departing executive director Tambra Dillon's thirteen-year tenure, the venue completed a significant restoration and expanded from a summer festival to year-round programming. Weinert inherits an organization that must balance artistic ambition with civic responsibility, drawing audiences from both New York City and the surrounding rural counties while serving a community increasingly shaped by urban migration.

In this interview, we discuss Weinert's transition from performer to administrator, his innovative research reconstructing Ted Shawn's lost choreography through agricultural labor, and his vision for Hudson Hall's role as both artistic incubator and community anchor. We also explore the changing dynamics of the Hudson Valley arts scene, the challenges of year-round programming in a regional venue, and how an artist maintains creative practice while taking on institutional leadership.

Lawrence Peryer: When someone asks you what you do, do you lead with one aspect of your work, or do you try to explain the whole constellation?

Adam: That's a question I think about often. A lot depends on who's asking. I use context clues to figure out what makes sense. When I was younger as a dancer, many dancers referred to something called 'dancer shame,' where people think that because you're a dancer, you're not this or you're not that, or you don't have these ideas about what you're doing.

As a counter-reaction to that, I tended to lead with 'dancer' to empower that role rather than think of it as something lesser. A dancer can be a connector, can be a creator, can be an interpreter—all the things that make someone a nimble, well-rounded person.

Taking on this new role at Hudson Hall and stepping into the executive director position, I think I am leaving my performer identity behind and now leading in this other space, which is more about building connections and creating platforms for artists, community members, and the place we live.

Lawrence: Do dancers have the shame issue because they're often the vessel for someone else's work?

Adam: I think so. I also think it's because dance is such a front-loaded career. Many people who dance professionally start training very seriously early, and many don't attend a four-year college program or have the wider array of what a liberal arts education might provide.

I actually transferred from Vassar College, where I was an economics major, to the Juilliard School for dance when I was young. A lot of people asked if I missed the intellectual rigor of Vassar College in this new setting, and I guess I did. But you're trading it for a community of people who are so talented, so disciplined, so goal-oriented that it became a very inspiring group to me for a whole other set of reasons.

Lawrence: Tell me about the role of place in what you're doing, because there's certainly a thread of rootedness in the different activities you've been involved with.

Adam: Absolutely. When my husband and I moved to Hudson eleven years ago, we had been living in New York City, where I grew up. But we mostly traveled for work—I was a touring dancer, he's an opera director. We thought we didn't need to be based in New York City anymore.

We both had connections to Hudson. I'd been doing summer dance residencies here, and he had a lot of friends from his childhood and college who'd moved here. Initially, we really thought of it as a base from which we would continue to travel. To a certain extent, my husband still does that. But I wound up putting down roots in a way that I didn't really expect, but which has been really rewarding.

That's taken different forms. One really powerful connection is in the agricultural work I started at the Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival, which is just about an hour away from here. That really clued me in to some of this connective thread between place and creativity—maybe, if you'll let me, a terroir of the performing arts. I've applied that in different ways here in Hudson with the Waterfront Wednesday series, which is now in its sixth year, a free weekly local summer festival that I helped start.

If you think about a performer on stage and how much the audience feeds into what they're doing, there is that sort of dialogue between the performer on stage and the audience in the room. I think that analogy also works when you think about an organization within a community, or even an artist working inside the community.

I am so fed by the creative energy of this place. I see that at Hudson Hall as well, where it is this really rare mix of internationally acclaimed performance and concert work, and then also very community-forward workshops and dialogue. I really love that duality because I think that one feeds the other and really creates a magical place to be.

Lawrence: I want to ask you about the work you did with Ted Shawn's choreography. Could you tell me a little bit about what was going on there for you in that specific project and what that represents to you as an ethos?

Adam: I love that question. Ted Shawn is considered one of the founders of American modern dance. He founded the Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival and created the very first modern dance technique. He trained Martha Graham, for example, who then went on to become much more famous than he was, and that was a real sore spot for him.

What I became really interested in was that dance is often taught almost like an oral history. You'll learn it from someone who learned it from someone who learned it from José Limón, or it has that kind of body-to-body transfer. But that wasn't available for Ted Shawn, in part because his all-male dance company in the 1930s—they all served in World War Two, and they didn't all make it back, and none of them really danced again following the war.

The process of reconstruction was very outside-in, and I used everything from memoirs and photographs to film and Labanotation, which is a nearly extinct dance notation form. Actually, the agriculture was part of that research. I recreated their daily training regimen, which actually included several hours of farm work every day. So I thought I should get into some of this farm work to try to embody what they had embodied.

I started performing the solos that he created, which were very simple. He was trying to figure out what was American about American dance. He rejected ballet, which he considered a bourgeois, Eurocentric tradition. He wanted to figure out what America looks like on stage, which is an interesting question to ask—and to ask again now, because it looks quite different now in 2025 than it did in 1925, especially when it was all wrapped up in masculinity and all kinds of questions that we've evolved our answers to.

But I have to say that his mission really unlocked for me when I reconstructed his ensemble work because, to your point about creative placemaking, he wasn't just interested in creating a dance. He was interested in creating a whole ecosystem that supported dance, hence establishing this farm and festival in the Berkshires, which is now the longest-running dance festival in the USA.

So I was really interested in trying to unlock, or follow the trace of, these footsteps of this person who'd created a new art form and established these enduring traditions.

Lawrence: You're not really a stranger to Hudson Hall, nor are you a stranger to arts administration. Tell me a little bit about your history with Hudson Hall, and, to the extent you know, why you are in this role?

Adam: My first time at Hudson Hall was as an artist-in-residence in 2014. That was a magical time before the restoration. Hudson Hall, the upstairs theater, which is now a beautiful state-of-the-art, 350-seat performance space, was at that time just a huge open room. I think there was one working electrical outlet and no working lights. For dance, open space is really all you need.

That residency was the beginning of the Ted Shawn project, which later premiered at Jacob's Pillow and toured around the world. That was my first experience of the way that this place can lift up local talent and put it on the national stage. That's exciting to me.

Over the years, I returned in different ways. I helped build a very silly, very fun show called “Rip the Nut,” a mashup of the Rip Van Winkle story and The Nutcracker Suite. We brought in local youth groups from all over the county, creating a huge spectacle that performed during Winter Walk.

I've been back in different ways over the years and just been a fan of the organization. When thinking about why me for this organization to help steward the next chapter, I like to think that it speaks to my roles in the community as well as in the art world. With my experience in touring and the connections I have in New York City, I am plugged in a certain way. But I think what made me unique was that I can straddle that with these deep local connections and partnerships in Hudson and around the region.

Some years ago, I helped found the Hudson Arts Coalition, a group of seventeen local arts organizations, to facilitate collaboration and coordination. This was necessary because there’s so much happening in this area these days, with new organizations popping up all the time. I think there was one year when two large organizations held their spring galas on the same day. The community up here is just too small to afford to do that. That was a wake-up call that actually we need to be in dialogue with each other so that, even if it's not possible to collaborate, at least we can avoid competition when possible.

So I think it's that sort of collaborative mindset, being a real member of this community, and then also having some chops in the world of dance and performance.

Lawrence: I was just talking to a friend yesterday, and there's an interesting executive director role for an arts organization near me, and I asked, "Are you going to go out for that ED role?" And he said, "I can't spend all day raising money."

Adam: Yeah. It's a thing. But my approach these first ninety days is to think of it as a kind of listening tour. I want to have deep and candid conversations with our staff, our board, our local community, and community partners, because I believe that a transition is also an opportunity to realign around our vision and perhaps make any necessary adjustments to our operations or mission statement—whatever that might be. So I'm going into this with kind of open ears.

Thankfully, there is a significant amount of programming in place that I don't need to scramble to book events. I get to be strategic in that way, and that's a real gift as well.

Lawrence: How do you think about the dialogue between the artistic institution and community, and the institution responding to the needs of your community? How do you think about what people want in the programming?

Adam: For me, it's very grounded in the history of this organization, or maybe I should say this building, because it was originally built as the city hall for Hudson. It was the town hall, it was the bank, it was the prison—it really just was the center of civic life in the city. I love that the organization has continued to hold that kind of sense of civic responsibility in the way that it programs.

This festival takes place over four venues in the city. Those are the main stage shows, which were all curated by the incredible Cat Henry and hosted by Kiana Faircloth. In addition to that, there is this "Sounds Around Town" series, which was curated by John Esposito of Bard College. That places these pop-up free performances all over the city—in parks, at breweries, even at the Amtrak station. For me, that's all about accessibility and discovery and just this sense that art is the fabric of everyday life in Hudson. To me, that's the magic of the festival.

Lawrence: How do you think about programming over the winter? You can't shut down, right? You're a twelve-month-out-of-the-year operation. Is that when you bring in the Kronos Quartet or something to lure people out of the house?

Adam: It's a question I'm looking to answer. One thing that I am looking to do is to formalize our artist-in-residence program. That's long been a part of what Hudson Hall does. When I think about my own story, or last spring, my husband premiered his "Giulio Cesare" at Hudson Hall—it's not just that the work premiered at Hudson Hall, it was built in that space over the course of a month. That's incredibly rare and I think incredibly powerful. So I want to build out these artist residencies for music, opera, dance, different art forms, and I think that is a great use of, say, these winter months when it's maybe a little more challenging to get someone to brave the snow and show up for a performance.

Hopefully, we will get those lined up, even starting this winter. But I do think it's important to keep some public offerings at least once a month. Historically, we've done a Valentine's Day kind of date night concert as a February offering. Our art gallery continues to program workshops, things like that.

I'll also say that tourism is not as robust in, say, the late winter and early spring as October. But that also means that there's less competition. Summertime can actually be really challenging in this area because there's so much going on between different summer festivals and all kinds of events that there can actually be a power to having a wonderful event in late January.

Lawrence: How do you think about the scope of the programming and the disciplines that can be represented, and are there types of work that you're not seeing in the region that you feel like you might be able to provide a platform for?

Adam: One thing that comes to mind is this recent opera series. I bring it up because it feels very tied to our venue for a few reasons. One is the scale of our venue. When I talk about the opera series, I'm thinking specifically about these Handel operas presented with the Baroque band Ruckus, which uses period instruments. I bring that up because our house is actually an ideal scale for that kind of work. Most opera houses are actually too large for these early Baroque operas. They get lost in the space, but ours is beautifully scaled.

This series has been wildly successful, both critically and in terms of its impact on our local community, which feels very grounded in the building’s history. To me, that feels like something we definitely need to be doing more of.

But realistically, we as an organization can't commission and produce operas all the time. We're a small and mighty team. So that makes me think: what else can we do to sustain that energy around this series between these large-scale operas that we can probably only do every eighteen or twenty-four months? Maybe it's a recital series. Maybe we have a holiday show of Handel's Messiah. How do we keep this series at the forefront of our minds and also within an ecosystem that we can support? I also think about a jazz festival. So I guess the point I'm trying to make is I'm looking at what's working and how we can really maximize and innovate in those spaces.

Lawrence: When you were on the other side of this as a patron, what types of programming made you leap off your couch and say, "I'm going to that!"?

Adam: My background is in dance. I'll always have a special place for dance. I think where I get excited, too, is in these kinds of preview performances. There's a nice tradition of these at Hudson Hall and in other venues in our area, where maybe an artist or a group has come up here to put their show on its feet before their New York City premiere. That is exciting to me. I feel like we get a sneak peek at the creative process, and we get to see it before they do in New York City. What's more fun than that?

I also think that it is valuable for the artists because, so often, a theater gives them little technical time to figure out their show in their own space, when it's just getting on its feet. For a lot of dance productions, you work and you work—maybe a year, maybe three years—and then you get two, three performances over one weekend, and that's it.

So building in these opportunities where you can put a dance on its feet, share it for an audience—that's such a gift to the artist, and I think it's also exciting for the audience. I'm always drawn to events like that, and I hope that’s a stream we can continue to support at Hudson Hall as well.

Lawrence: As your administrative responsibilities grow, how do you maintain your creative practice?

Adam: That's a question I also have. I shared a new choreographic work as recently as June. I love teaching, which—I don't know that I will continue to make choreographic work, but I do want to continue to find space for teaching because I love the way that keeps me in the studio and in my body. I also really enjoy writing, and I have a drawing practice and a gardening one. So I think that those will scratch that itch for me.

But one thing that excites me about this opportunity at Hudson Hall is that it feels like a place where I can weave back together all of these skill sets that I've honed over the years, because I get that it is one place where I think I will need to tap into all of them. I will be budgeting, creating, and all of those different threads. But I can do it in my home community now and within this institution with these beautiful coworkers. There's a way that I'm looking forward to the coherency of that.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmSara Jayne Crow

The TonearmSara Jayne Crow

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments