In the early 1980s, while engineers at MIT struggled to program a cube to rotate, Tamiko Thiel already envisioned how computer graphics could be more than a technical novelty. Her story, from product designer of the iconic Connection Machine supercomputer to pioneer of virtual reality art, illustrates how technology can express complex social realities when guided by humanistic intent.

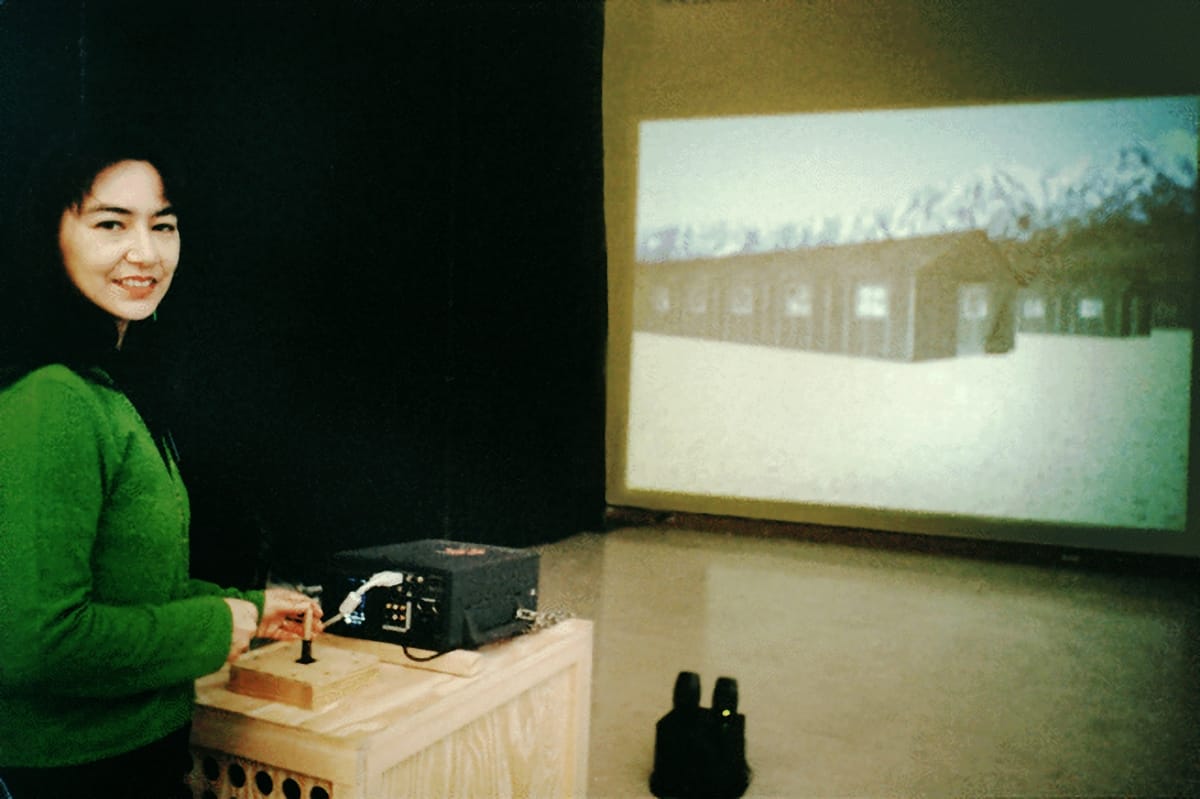

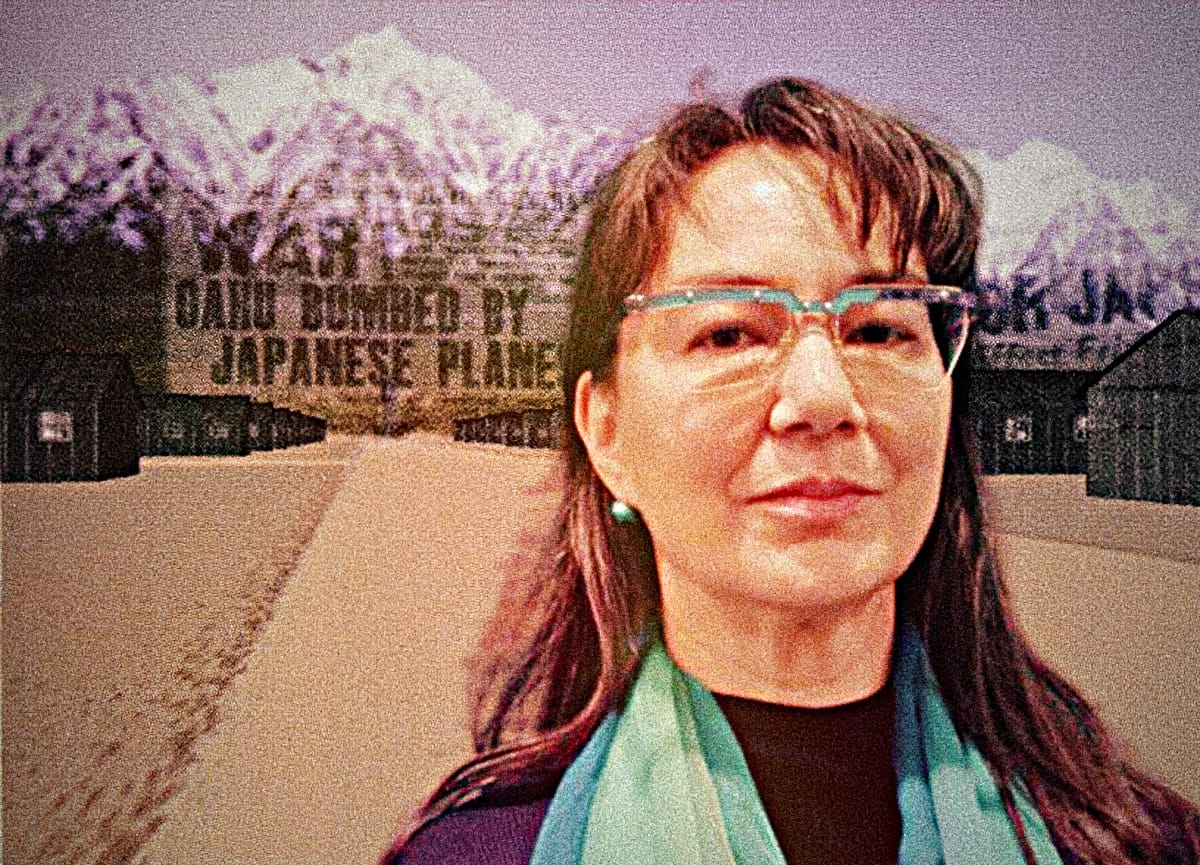

Thiel's most significant contributions emerged when she turned from designing computers to using them as artistic tools. After studying traditional media at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, she became increasingly drawn to installations that engaged viewers in physical space. Her interest in how environments evoke emotional responses led her to virtual reality. Thiel saw VR as a medium that could place viewers within constructed worlds that tell stories conventional media cannot. This approach culminated in Beyond Manzanar, 2000, her groundbreaking collaboration with Iranian-American artist Zara Houshmand that reconstructs the World War II-era Japanese American internment camp while drawing parallels to the threatened detention of Iranian Americans during periods of political tension.

Through virtual reality, Thiel creates art that asks audiences to occupy uncomfortable positions—to experience, if briefly, the perspective of those imprisoned for their ethnicity or nationality. "I wanted to put you in shoes you might never want to wear," she explains of her intention with Beyond Manzanar, now in the permanent collection of the San Jose Museum of Art. This empathetic purpose runs through her subsequent works, including Virtuelle Mauer/ReConstructing the Wall, 2007, which won the IBM Innovation Award for artistic creation, and her more recent augmented reality installations like Gardens of the Anthropocene, 2016 and Unexpected Growth, 2018, the latter commissioned by the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Tamiko Thiel returned to the Spotlight On podcast to continue her conversation with host Lawrence Peryer. In part two of this discussion, Thiel discusses how her unconventional background—from mechanical engineering at MIT to art studies in Munich—shaped her approach to virtual spaces. She reflects on the psychological power of spatial experiences and explains why 3D environments can communicate emotional truths that are missing from traditional media. You can listen to the entire conversation in the Spotlight On player below. The transcript has been edited for length, flow, and clarity.

Rotating the Cube

Lawrence Peryer: I'm interested in how you came to not only embrace virtual reality as an artistic medium but to use it to explore a complicated historical narrative in a way that perhaps traditional media wouldn't have been appropriate for.

Tamiko Thiel: A bunch of things come together there. One is that I started working with computer graphics as a graduate student in 1982 at MIT. Graphics was really at the stage where I remember one of the other students taking a whole semester to program a cube to rotate, because you had to write everything yourself—really the full stack. And I was thinking, "I don't think I want to use this for artwork right now."

Roughly 12 years later, I graduated from art school. After painting and drawing, wanting to go back to the basics, I had started working with video at some point. I'd been doing installations of found objects. My earlier career as a product design engineer was always creating 3D objects—the terminals at Hewlett-Packard and then the Connection Machine at Thinking Machines. So maybe it's not surprising that I started with painting and drawing, but then began working with 3D found objects and making installations out of them.

When I started working with video, which has a time-based component, I was trying to develop a dramatic structure in time. I said, “Well, okay, I know how to make a single image with a strong composition that attracts and holds your attention. But how do I do that, so to speak, 25 times a second for five or 10 minutes?"

To access that way of thinking, I started going back to my father Philip Thiel's work on perception of a person moving through a space, whether that's the space of a building or the space of an urban environment, and how he was looking at musical structure that creates development of a dramatic arc in time or theater or any of these time-based arts.

But the thing is that all of the traditional arts, theater, and novels, especially, focus very much on characters, on projecting yourself into a character. And so everything I could read about creating time-based structure at that point said if you don't have characters, you can't have dramatic structure.

Lawrence: Yeah, you must have conflict and the arc.

Tamiko: The dramatic arc, yeah. And I thought this was not true because there's plenty of music that touches us emotionally, much stronger than any of the other arts, without having characters. They might have themes, but they're certainly not human beings, and you can't project yourself as a human being into a musical theme in the same way that people are talking about doing it in a novel or a theater piece.

Also, if you've ever climbed a mountain or if you've ever sat on a beach and watched the sunset, you are going through a dramatic arc. And that's why there's this exhilaration when the sun finally sets, when you finally get to the peak, you can't get any higher, and you have this panoramic view around you. You have gone through a dramatic arc in time, and it produces emotions in you. And then there’s the denouement, whether the world gets darker because the sun has set or because you're descending the mountain, and so you're recapitulating your progression. You're seeing it differently.

The main character is you. You're not projecting yourself into another character and watching them climb the mountain. But that said, to me, all this drama theory that says you need characters is wrong.

So I was reading my dad's book where he was talking about the components of physical spaces that cause different emotions in you, and why can the same space be a positive space in one case and a negative space in the other? And I was working with video, just abstracted images of video, and trying to understand how to create this dramatic tension and build up and a release.

I graduated with a video installation that I then showed around and got a lot of positive feedback. But then I found myself wanting to have multiple screens. So my second video piece was five screens on top of each other. Then after that, I wanted to essentially take a room and put screens all over the room—small screens, big screens, et cetera. In those days, and we're talking mid-1990s, for each video screen you’re driving, you need to have a video player and synchronize them. It's a tremendous amount of hardware, and there was no way that I, as a beginning young artist, could command the sort of money that I needed for all those screens.

And by happenstance, I had moved to San Francisco in the fall of 1994 and needed a job. And friends of mine said, "These friends of ours have started a company they call Worlds Incorporated, and they are doing virtual reality on the internet with the new sort of standard.” This graphic standard allowed you to do online interactive, real-time 3D computer graphics with avatars. We were calling it cyberspace—that Johnny-come-lately Mark Zuckerberg somehow managed, by the force of his billions of dollars, to rename it to the metaverse fairly recently.

When I went and talked to Worlds Incorporated, they said, "Well, we've got this project working with Steven Spielberg to create a virtual world for seriously and chronically ill children, and it's a pretty high profile and high risk, and we desperately need someone who knows the artistic side and the technical side." And not many people in the world at that point had substantial experience in both. They were excited to hire me as a producer and creative director. So I ran that project from 1994 until 1996, and that was when I started working with computer graphics with virtual reality.

We were calling it virtual reality in those days, even though today, when people say—and in general, in the technical world, mainly—when you say virtual reality, you restrict yourself to saying only things seen in stereo in a helmet.

Lawrence: Yeah. People think of hardware—or Jaron Lanier's dreadlocks.

Tamiko: Yeah, exactly. So, back in those days, there were stereo headsets that made everyone nauseous after 10 minutes, and they were cumbersome. The other alternative for stereo VR was “caves”—a room with rear projection, projections coming from at least two or more sides that required, in those days, an immense amount of space and an immense amount of equipment because a single computer was driving each projector. The computers had to be networked together, et cetera.

So everything you had to do for stereo VR at that point was costly, made everyone nauseous within 10 minutes, and was just not reasonable, especially when the doctors said, "Listen. These kids are seriously or chronically ill. They have cystic fibrosis, they have cancer, they have all these really heavy diseases. They are constantly nauseous because of the medicine they're getting. They are hooked up to machines, encased in machines. They don't need more of that."

In the commercial vein, this technology became the technology of 3D interactive computer games and the massive multiplayer games that would run over the internet. But there was also a standard called the Virtual Reality Modeling Language. And this was a 3D version of HTML.

I spent the next 15 years building three vast virtual worlds. I didn't run them online because I wanted a more intimate experience. I didn't want people coming, showing up as avatars and doing, you know, the standard things that people do. The best you can hope for in a virtual conversation is, "Hi, my name is so-and-so, where are you?" And I wanted to have an encounter like the person climbing a mountain. The person climbing the mountain doesn't need someone in front of them all the time saying, "Oh, and look over here, and now look over here." It's like, "Be quiet. I want to be alone. I want to look at the scenery."

So these three pieces that I created—you, as the main character, are encountering the virtual world I've created for you, and you're supposed to experience that space and what is in that space. You're not supposed to go off and be talking to someone who doesn't care about the space you're in. They're just saying, "Oh, isn't this cool technology?" No, those are distractions I was just not interested in.

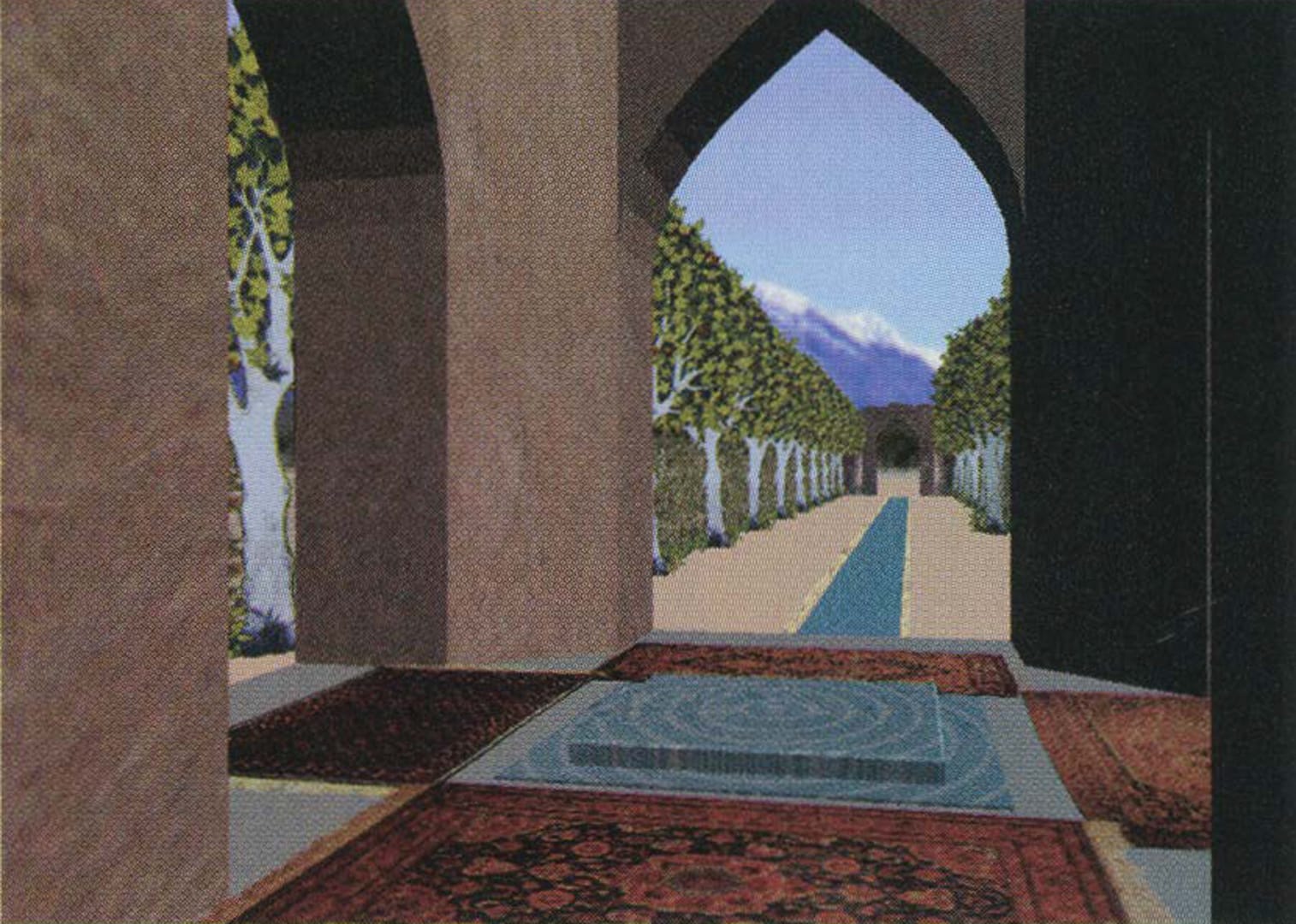

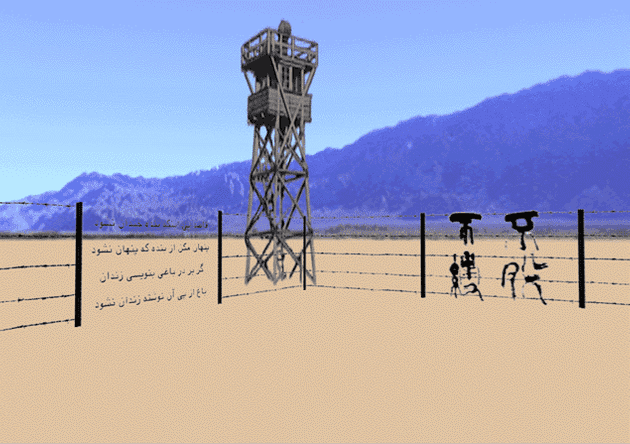

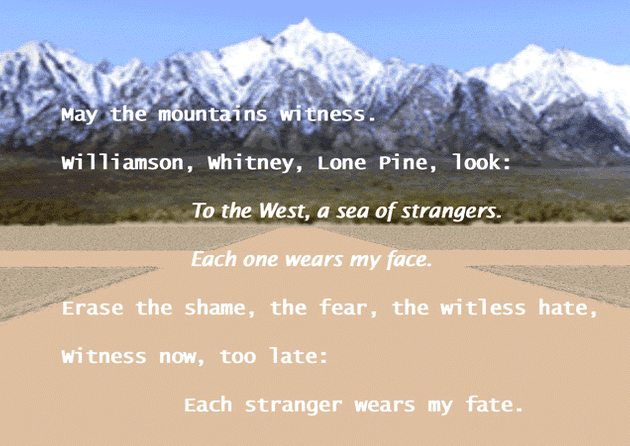

Screenshots from Beyond Manzanar.

And then the other factor specifically with Beyond Manzanar is, there was another woman, Zara Houshmand, at the company who had a background in doing these multimedia presentations—for instance, for the Shah of Iran. She's Iranian-American and was in Iran for a while before the revolution. She got out before that and was working in theater, and she's a published poet and an excellent translator of Rumi poetry.

And so the two of us started from the beginning, talking about what could be done with this medium to create works of art. Because we were all doing things like Starbright World, which I was working on—the 3D metaverse for children. You could call it a work of art, but the focus is on the kids’ needs and how we provide them with a space that frees them from the confines of their hospital room and their hospital beds.

And then in 1995, there was a bomb attack in Oklahoma City. Zara was off on a meditation retreat in the High Sierras. Right before the retreat had started, she had heard about this attack, and she recalled the first attack on the World Trade Center two years earlier, which was done by Islamic terrorists.

And so Zara's thought as she's entering this week-long silence, no media from the outside world, focused just on the meditation, was, "Oh my God. What if, when I come out, it turns out that Iran was behind this latest attack, and there are police waiting for me to take me and everyone of Iranian ancestry into a concentration camp?"

When she came out a week later, we had found out, no, it wasn't Islamic Middle Eastern terrorists. It was a bunch of white, right-wing terrorists. And she was off the hook, so to speak, but shaken up by this experience and knowing that Manzanar, the very first of over 10 concentration camps that were built in World War II to imprison people of Japanese ancestry, was just down the road from where she was doing the retreat.

She went and visited the Manzanar site and was struck by its beauty. How it reminded her exactly of the landscapes of Iran, of mountain landscapes—snow-covered mountains, high plateaus, high desert plateaus, and the snow melt from the mountains create these oases where people would build gardens in the middle of the desert, and they would build a wall around it to keep in the moisture.

She said Manzanar looked like a Persian garden that the desert had taken back. All of the barracks at that point had been long gone; they disappeared right after the war because there was not much wood to build with in the desert. There was this grid of harshly tiered paved roads in the camp, this grid in the middle of the desert, and she says it's just like the grid of an Iranian paradise garden. In Iranian Persian culture, this sort of geometric grid is an indication of the perfection of paradise. And by the way, do you know that the word paradise comes from the Persian word "pardis"? The Farsi word "pardis," which means a walled garden?

She's going on and on about having these images of gardens in Manzanar. And I said, "Wait a minute." And I Googled "gardens in the desert" and immediately what came up was a photograph Ansel Adams took of a Japanese paradise garden in Manzanar during World War II. I could tell immediately it was a paradise garden because there was a rock that looked like a turtle, a sign of longevity, and an island that looked like a crane, another sign of longevity. These are the signs of a paradise garden in a specific tradition of Japanese garden design. And I said, "We've got an art project." And five years later, we had finished it.

That was the way it all started: with an image that was so strong and so layered with the actual site of Manzanar, the historical experience of the Japanese Americans imprisoned in Manzanar during World War II, and then the parallel, but very different, experience of Iranian Americans threatened with similar internments for the crime of being the face of the enemy.

I mean, we finished Beyond Manzanar a year before the attacks on the World Trade Center. Exactly what Japanese Americans had seen in World War II started happening again. Exactly what Iranian Americans had seen at the time of the Iranian hostage crisis started happening again. And now Trump has started doing it yet again. And so that's what the piece is about.

With my background, working with virtual reality and thinking with my father's theoretical background about the experience of moving through space, being in space, what space says to you, what your environment says to you—Zara, with her theater background, very strongly influenced by Bertolt Brecht—it was a deep dive into how to use this new medium. We wanted to put you in the shoes you might never want to wear. To put you in the shoes of someone else and then take you through a dramatic experience that hopefully will give you some inkling of what it's like when you are being imprisoned for no fault of your own.

Clear and Present Danger

Lawrence: I’m discerning the recurring themes across our conversations: you have this history of ingesting technology in various academic or commercial contexts before you've necessarily thought about the artistic application. You become familiar with them and quickly pivot to the artistic application. But this social element also runs through the art, right?

Tamiko: Yeah, very much so. I mean, I have to say, my dad was a real Bernie Sanders type of guy. And in fact, they're both from Brooklyn and have very strong Brooklyn accents. My father is dead, but I hear his voice every time I listen to Bernie Sanders speak. And they're both like, essentially, 1950s socialists. So I grew up with Dad's Bauhaus aesthetic and his social aesthetic, and people who know my father know that in Seattle, he was always essentially a social activist for a better urban environment.

I grew up with that sort of perspective, and I often try and make completely nonpolitical artworks, and it doesn't work.

Lawrence: Yeah, I was going to say, I don't buy that for a minute.

Tamiko: It always sneaks in—especially ecological issues, both because they're very important to me and because that has a much broader scope than pieces that explicitly critique politics or religion or our hangups about the body. Ecological themes are a little bit more general.

Lawrence: Do you have a philosophy or a grand theory about the relationship between people and technology? You talked about how you don't want to build the tools, you want to make art with the tools, yet you've been in environments where, because you were on the bleeding edge, you had to participate in the making of the tools. So you've been someone who's watched the definition of the pace of change—what used to take decades takes business days.

Tamiko: Well, that's specifically with AI, right? And I think that is a development I've watched happen from the 1980s when I got involved with the MIT AI Lab, and how it just struggled behind the scenes until roughly 2012 or 2015.

Usually, there's a huge acceleration when a bunch of pieces of technology come together and enable you to make a new step. We are in a period where there's so much happening to take us a big leap forward, just as we were with the VR technology in 2015 or so, before it ran out of steam. There are a lot of applications of the current state of AI technology that haven't been implemented yet, maybe because of realistic worries about what that does to the humans affected by that technology. So there is a sort of AI backlash that's happening now, which might hopefully slow things down a bit, because there's this tendency in humans to suddenly ascribe tremendous powers to a black box, and abdicate responsibility for what happens as a result.

And so there's all of these people, a lot of them women by the way, who have been parts of Google and other AI companies who have been saying, "Stop worrying about the danger of general AI, worry about how AI is starting to be built into systems that affect our daily lives without being questioned." They lose their jobs; they get kicked out of Google. No one pays attention to them. Instead, everyone pays attention to the billionaire tech bros who say, "Oh, well, you know, maybe a general AI is going to come and like kill us all," or something like that. And that's a perfect cover because meanwhile, the AI companies and anyone who wants to implement AI without having any sort of social watchperson talk about it, can go off and just do it as they damn well please. They build it into systems that evaluate whether we should have a job at all or whether we should get social security.

I tell this example of a friend who was told, “Okay, develop an AI system that assigns foster children to homes”—that was all she was given. She wasn't told, "Okay. Here is a professor studying how children should be assigned to homes, and you will work with them.” She refused because she thought it was wrong. And so, of course, they gave this job to the next person who graduated with the same diploma. And that's the clear and present danger—what humans are doing with the technology right now.

Lawrence: I would argue it's been maybe 25 years since you couldn't function in the modern world without being fully internet-enabled. Suppose you unplug it now or unplug it at the individual level. In that case, you don't necessarily need to disappear or detain people physically if you were to forbid somebody from having internet access. They wouldn't be able to be a participant in modern society. With that terrifying reality, it’s a wonder your art is not dystopian.

Tamiko: Well, that was kind of a decision. It's easy to make dystopian art, and it can be powerful.

I give a lot of lectures for university students with the awareness that we are killing off the planet at a rate never seen before on the face of the earth. When I started realizing, "Okay, the students know it and they're the ones who have to deal with it," then I thought, "I can't tell young people who already know how badly my generation is screwing them over. I can't just sort of laugh at them and say, 'Oh, you know, I'm going to make all this art and I hope I make money doing it, and it's all about how we're shafting you and your kids.'"

So I started looking for ways to send a message like, "Okay, the situation's bad, but this is something we can do to improve it.” I think realistically, the only way that's possible is if we change the government or we change several governments worldwide. Because if one government wants to wage war, how are you going to keep that carbon footprint for the whole world in check if someone's just burning up another country?

Lawrence: You bring me back to the fact that when we first started talking, I wanted to distinguish us as being, not techno-utopians, but techno-optimists. I find it impossible to be a techno-utopian and not that attractive, as it involves outsourcing responsibility to the technology. I'm not interested in that. But where I'm landing is the humanity and the empathy you're transmitting, and there is an optimism, which should be the proper role for the technology. It has to be our tool for transmitting humanity and empathy. Without that, we don't get good outcomes. So, thank you for reflecting that through your work.

Visit Tamiko Thiel at tamikothiel.com where you'll find extensive documentation of her digital art and news of recent projects and installations. You can follow Tamiko Thiel on Bluesky, Instagram, and LinkedIn.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments