Most composers work with sound. Stephan Thelen works between sounds, the mathematical relationships that govern rhythm, and the collision points where disparate sonic worlds meet. His latest album, Worlds in Collision, represents a return to electronic experimentation as well as a significant departure from his previous work with the minimal-progressive band Sonar. The Swiss mathematician-turned-composer has created something that functions as much as a philosophical statement as a musical artifact. The record is a meditation on how speech, rhythm, and electronic manipulation can create meaning through fragmentation, rather than relying on melody or hooks.

The album emerged from Thelen's fascination with Brian Eno and David Byrne's My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, but his approach differs fundamentally from that 1981 landmark. Where Eno and Byrne used tape editing to create 'collage music,' Thelen and collaborator Fabio Anile employ digital tools to fragment voices in ways that follow the polyrhythmic structures underlying each composition. It's sampling as the foundation rather than a decoration. The human voice becomes another instrument subject to the same mathematical principles that govern Thelen's use of prime numbers, Fibonacci sequences, and geometric patterns in his compositional process.

Working with accomplished improvisers David Torn and Jon Durant, Thelen's album finds acoustic drums coexisting with processed voices, field recordings from Sicilian markets pounding out rhythms, and feedback used as a compositional device. The result challenges notions about what happens when precise mathematics meets intuitive expression. As Thelen explains his process and philosophy, he reveals an artist comfortable with contradiction. He's someone who uses objective structures to create subjective emotional experiences and finds mystery in equations, as well as human warmth in the rigidity of algorithms.

Lawrence Peryer: The collaboration with Fabio Anile on your album Worlds in Collision was inspired by a shared reverence for Brian Eno and David Byrne's My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. When you mentioned this influence in an email to Fabio, he immediately wanted to contribute. How did that initial exchange shape the entire direction of the album?

Stephan: Eno has often described himself as a 'non-musician,' and Fabio kept pushing me in a more radical and 'non-musical' direction, abandoning traditional melodies and solos and concentrating on more fragmented and experimental sounds. For example, he didn't want to play piano on the album and decided instead to use the electronic sounds of his vintage Roland D-50 keyboard. The decision to include sampled voices also changed a lot and became a main focus of the album.

Lawrence: My Life in the Bush of Ghosts was groundbreaking for creating what Eno called 'collage music.' How did you and Fabio approach this album differently than Eno and Byrne did in 1981?

Stephan: I think Eno and Byrne were actually editing tapes, because samplers were not available in 1980. Now, with a laptop and software like Logic Pro, manipulating recorded voices is very easy and can be done very quickly. We used the full range of digital effects to treat the voices—distortion, EQ, delays, pitch shifters, tremolo—but also new effects like putting them through granular synthesizers.

Fabio had many ideas on how to treat voices in ways that Eno and Byrne had not used. His main idea was to cut up the voices in a way that, in a sense, 'followed' the polyrhythms that were used in a piece and also to split them up in the stereo field.

Lawrence: Your background includes a PhD in mathematics, as well as musical training on classical guitar and participation in Robert Fripp's Guitar Craft seminars. How does a mathematical foundation inform your compositions, particularly these complex rhythmic structures we're hearing on Worlds in Collision?

Stephan: Since I can remember, I have always been fascinated by prime numbers, Fibonacci numbers, geometric structures like the Möbius strip, patterns, tilings, symmetries, and this fascination always finds a way into my compositions. I often use polyrhythms with odd meters and isorhythms, so I'm constantly making simple numerical calculations like the least common multiplier.

The use of mathematical structures in music is a very strong tool to generate musical ideas that you wouldn't get by just playing by ear. These ideas have an 'objective' and timeless quality that you probably couldn't get otherwise. I agree that human or 'subjective' emotions are what make music matter, but mathematically generated ideas can also have an emotional content that reflects a deep sense of mystery.

I also often use a technique that I call 'twofold covering,' a term I borrowed from differential geometry, where I 'cover' a melody by the same melody that is played half as fast and one or two octaves lower. One example of this technique is the piano on the track "Voices from the Ether."

Lawrence: The song "Worlds in Collision" is rare in your catalog for being in 4/4 time, although you layered a simultaneous 5/4 beat for polyrhythmic complexity. What draws you away from standard 4/4 time, and how do you tackle these multiple time signatures practically?

Stephan: A very, very large percentage of Western music is in standard 4/4 time with a steady backbeat. After hearing these beats for about sixty years now, I admit that they really sound extremely boring to my ears, even if they are well played. It's like everything would have to be in C major.

So I put a lot of energy into creating new rhythms that are not in 4/4, but still flow and are accessible to the body and to the ears. I usually compose them for drums and bass, so they are very open to being orchestrated in different ways. A 'three against four against five' beat like the one used in the Kronos piece is such a fascinating rhythm that I keep getting ideas on how it could be used in surprising ways.

In the beginning, it's hard to hear them as one complex organism, but with a lot of practice, you eventually reach a point (that we call 'paradise') where you can freely switch your attention between the individual beats or listen to them as one pattern. As for composing polyrhythms, I usually start with a conceptual idea and try this idea out with my computer.

Lawrence: Let's talk some more about specific tracks. "Palermo" became the blueprint for the album, featuring field recordings Fabio made at the Ballarò market in Sicily and an 11/4 rhythm similar to "GongGong" from your Transneptunian Planets album. What made this track the perfect template for the direction you wanted to explore?

Stephan: It's a really cool and stomping rhythm in 11/4 that still flows wonderfully. It's simple and complex at the same time, and it's a fantastic beat for a drummer because it allows endless variations and different kinds of subdivisions. David roars over this beat like only he can. He played about seven improvised takes over the whole piece, and I spent a large amount of time editing them down to one explosive and expressive track.

Lawrence: "Atomic" samples President Truman's 1945 speech about the atomic bomb and uses the same rhythmic structure as Sonar's "Skeleton Groove." How does the historical weight of the Truman sample interact with your rhythmical mathematics?

Stephan: Fabio cut up the Truman sample in a way that some words are repeated after three beats, while others are repeated after four or five beats. Together with the historical significance of his words, this has a very interesting and almost uncanny effect.

Lawrence: You've mentioned that after years of playing clean guitar in Sonar without effects, you felt an urge to return to effects as integral musical elements. What prompted this shift back to your pre-Sonar techniques, and how did working with David Torn influence your approach to feedback and effects?

Stephan: Shortly before Sonar, I had a twenty-four-channel mixing desk in my live setup with sequencers, loop machines, synthesizers, effects, a MiniDisc player, and a guitar all hooked up to the mixer. It became so complicated to manage that I was spending way more time on technical things during a concert than on actually playing guitar. So when Sonar started, I really wanted to take a break from all that and concentrate on playing guitar without any effects (except reverb).

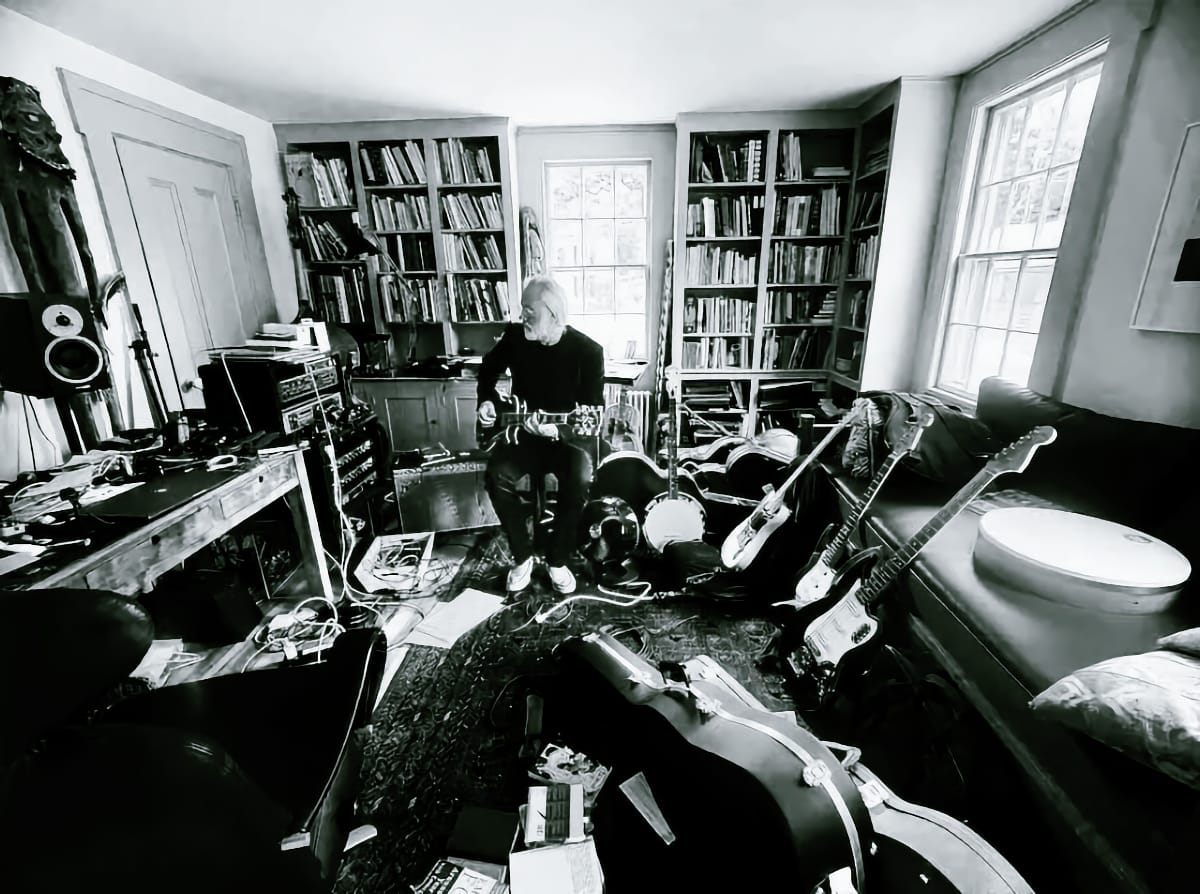

After a few years, however, I saw what some of my guitarist friends like Markus Reuter or Eivind Aarset were doing with effects and felt the urge to get some new effects myself and start experimenting again. Although feedback has been around for decades, I had the feeling that we were onto something new in the way David was using feedback, together with his looping machines, and making the whole recording room an almost unpredictable extension of his instrument. The basic question was about what happens when a feedback signal is put into a looping machine, so that you basically have two kinds of feedback, an acoustic one from the room and an electronic one from the looping machine.

Lawrence: Working with accomplished improvisers like David Torn and Jon Durant, how do you balance directing them toward your vision while leaving space for their individuality? And how did you balance the organic energy of live drums with the exacting electronic manipulation that the concept demanded?

Stephan: David and Jon know very well what I like, so first, I just let them roar away, basically without guidance. Then I'll give them feedback and let them do a second or third pass. They are both skilled improvisers who usually do their best work when they can react intuitively to the music.

My mixing techniques are completely intuitive and mainly self-taught. I don't use a lot of plug-ins and usually just rely on equalizers, compressors, and reverb to get the sound that feels right to me. An important part of a mix is also the stereo image, which probably has a lot to do with my love of geometry. In the future, I would like to mix in Dolby Atmos. I have watched other people mix in Dolby Atmos, and experiencing immersive audio is really fascinating. I am building a new studio for myself at the moment, and it is going to be a Dolby Atmos room with twelve speakers.

Lawrence: Given your mathematically-informed compositional approach, what role does intuition play in your creative process?

Stephan: For me, a composition almost always begins with an idea. It may be a mathematically inspired idea, but that is not necessarily the case. As soon as I try to create a piece of music that is based on that idea, I use my intuition to guide me through the process. If my intuition tells me that the piece doesn't have enough emotional weight, I will probably drop it. I have always believed that it's possible to create music that is intellectually satisfying and has an emotional depth, so that is always what I'm aiming for.

Lawrence: With your extensive output—five albums from 2021–2022 alone—plus your work with Sonar, Fractal Guitar projects, compositions for Kronos Quartet, and now this speech-sampling exploration, how do you maintain distinct artistic identities across these different contexts?

Stephan: Hopefully, a listener who hears different projects of mine will detect my musical personality, so in that sense I see them as facets of a unified artistic vision. Or you could say that the projects are different dialects of the same language.

I think I work in a similar way to Swiss composer Nik Bärtsch. Nik composes so-called 'modules' and then uses these as the foundations for pieces that he plays in his many different projects. So it's possible that one specific module will be played in many different settings, like a solo piano piece or an electric band with drums. It will sound totally different depending on the project, but it's still the same compositional idea. I don't, perhaps, have a name for them like Nik does, but I also have a catalog of core ideas that can work in many different musical projects.

Lawrence: The album title Worlds in Collision refers to the sonic worlds colliding within these pieces. As someone who crosses the worlds of academic mathematics, minimal rock, experimental guitar, and now sample-based composition, what have you learned about making disparate elements cohere into something that feels inevitable rather than forced?

Stephan: I have learned to trust my intuition and not to be afraid of trying out any idea that presents itself, even if it seems crazy. I have also learned to be patient when ideas don't immediately work and to persist. The only real question a musician or an artist has to ask herself or himself is when to say that a piece is finished, and I now spend a lot more time thinking about this than I used to.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments